On Nov. 9th, 2022, a general strike was called by Greece’s major public (ADEDY) and private (GSEE) union federations, coming at a critical time for the working and popular classes.

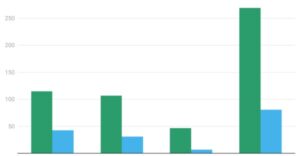

According to the official numbers, inflation was at 12% in September. The bank of Greece warns that this rate could probably hover over 10% in 2023. This data is obviously important, but the real cost of living for households is far worse. In 2022, during the last ten months, the price of bread (and other flour-based foods) increased by 19.3%, meat increased by 17.3%, dairy by 24.2%, cooking oil by 16.6%, natural gas by a whopping 68.4%, heating oil by 20.8% and transportation by 30%. This wave of price increase rapidly wears off salaries’ buying power. A study done by a union revealed that among the households who earn the monthly (legal) minimum wage (750 euros per individual), the loss of buying power amounts to 40% of earnings. One must keep in mind that Greek workers’ wages have stagnated since 2010 and that social security retirement pensions have been reduced (up to 40%!) since 2010. Meanwhile the counter-reforms promulgated by three [European Union/EU] memoranda in a row led to the fact that the wages of a huge part of the working class do not exceed the minimum monthly salary.

These conditions did exert pressure on the top union confederations’ bureaucrats to call for a 24-hour general strike. Another factor that led to this decision is the example of the international situation: such as the general strike announcements in England, Germany, France, Belgium, etc. The latter are becoming very popular among the workers who are beginning to consider them as a “model” of action.

The strike was called rather soon which gave ample time (more than a month) to prepare for it. One could not expect a strong preparatory mobilization coming from the union bureaucracy. After many years of inertia, it is highly improbable that they could mobilize a greater part of the working class, even if theywanttooccasionally. The call for strike was amplified by the organized left within the unions – mostly the Communist Party and the radical/anticapitalist left – who went head over heels to prepare for the strike and mobilize the working class.

This conscious effort went along with a generalized anger and indignation within the working class that translated to numerous “small scale” wildcat actions. For example, the struggle against layoffs and union busting at “Malamatina” a wine manufacturer; the fight against privatization of Larco’s iron and nickel mines; the struggle in the ship and iron yards against brutal working conditions; the pioneering fight of the delivery workers of E-Food and Wolt [a Finnish company]. The mobilization effort has favorably resonated with public sector employees who havealready expressed their resistance– mainly in hospitals, schools, public transportation and also among municipal employees – and are the backbone of the organized working class in Greece.

***

The end result was a strong success for the strike. The latter was the most substantial since the defeat of the social movementsafter the betrayal of Alexis Tsipras’ SYRIZAgovernment following the results of the July 2015 referendum [61.3% voters opposed the “propositions” from the EU creditors]. Beyond the public sector unions’ bastions, the strike was equally followed in the private sector.

Strikers’ demonstrations in Athens, Thessaloniki, Patra and in 75 other small towns were marked by a strong showing and a militant expression of working-class anger. In Athens, the police counted 20,000 demonstrators, but the truth is that the demonstration was at least twice as big. Numbers are always important, but there are other more qualitative and political facts. For the first time since the rightwing party victory in July 2019, the composition of the striker’s ranks wasn’t limited to the organized militants from the left. What was evident was the presence of wider layers of workers under their union banners, chanting their slogans and expressing their demands.

In the tradition established during the preceding years, there were distinct rallying “clusters”; one around the communist party and its organization PAME (a multi-union coalition), another made of two big, federated union organizations (ADEDY and GSEE), another regrouping the radical/anticapitalist left. This time though the scale of the rallies in Athens de facto united the different “blocks” in a single stream of strikers that flooded the streets of the city center during hours. Within this stream of strikers could swim “like fish in water” students who are opposing the permanent police presence on their campuses, feminist organizations who fight against widespread sexism, small shop owners who are worried for their survival, etc.

It is obvious that the November 9th strike could probably constitute the beginning of a progression in the coming period of workers’ struggle. The crucial question is therefore where do we go from here? This question is not very pertinent for the top union bureaucrats who called for the strike mainly to discharge themselves from their responsibilities and quelch the pressure from their base. These leaders, mainly from the GSEE and ADEDY, are satisfied with the success of Nov. 9th and refuse to organize any debate about the next step. The question is crucial for left unionists who were the ones who mobilized for the 9th and must now tackle the question of unity in action of the unions [with the presence of structured political forces within], as a precondition to push for anescalation of the struggle.

It won’t be a cake walk. The KyrokosMitsotakis government has protected the system with a law that makes even harder workplace union organizing and above all striking. Legal changes in employee relationships don’t bode well for spontaneous expression of working class militantism. But the success of the 9th shows that we have reached, it seems, the tipping point in this process.

The success of the general strike will inevitably have political repercussions.

First, we are talking about a resounding contention of a bragging claim of the government according to which Mitsotakis is capable of imposing the most provocative neoliberal counter-reforms, while simultaneously keeping workers paralyzed and inactive. The “message” has shown that this situation can be reversed and is encouraging for many in the popular classes. But it also constitutes a warning for the powers that be.

The working-class awakening of the 9th November just happened at a “delicate” moment for the Mitsotakis government. The country is scandalized about the revelations of widespread surveillance of numerous personalities (politicians, journalists, CEOs, etc.) by the National Intelligence Agency (EYP, under the immediate command of the prime minister’s office), in collaboration with private companies that sell spyware such as Predator (the product of an Israeli company which established itself in Athens with Cyprus as an intermediary). When it was revealed that EYP employed Predator to spy on the head of PASOK Nikos Androulakis, the prime minister was forced to fire the coordinator of his office and the head of EYP to get out of the mess. More revelations showed that among the surveilled were former ministers and politicians of SYRIZA, the former prime minister and ex-leader of New Democracy, Antonis Samaras, as well as the current minister of foreign affairs, Nikos Dendias. The big surprise came when it was revealed that among the victims of Predator, there was also the oligarch VagelisMarinakis (shipowner, media magnate and owner of the famous Olympiakos soccer club), as well as close relatives of the Vardinogianis family [with interests in oil and gas, sea transport, etc.], who is doubtless the most powerful capitalist conglomerate in the country.

VagelisMarinakis has already expressed his anger at the government, targeting Mitsotakis for having allowed the establishment of a “fascist network” within the government, in open violation of the constitution. The coherence of the New Democracy party and the survival of the government will depend on the next revelations on the surveillance scandal.

But the synchronization of a crisis at the top (the explosion of contradictions and conflicts within the ruling class…) and the growth of militantism from below (with the Nov. 9th strike as a signal) makes a nightmarish scenario for Mitsotakis. The carefree days of his unobstructed domination – when he had to face mainly the weak and meek opposition of SYRIZA – are over. On the political arena we are living through the beginning of the end of a government extremely reactionary and dangerous. The question is to know whether the workers and social movements will find a way to transform the government crisis into an opportunity to put forward the needs and demands of the workers and to fight to impose them. The success of the Nov. 9th general strike allows us to consider this question in a more optimistic way.