On May 21st, parliamentary elections were held under the proportional representation system for the first time in Greek history. In 2016, the coalition government of SYRIZA and ANEL (Independent Greeks) had abolished the “traditional” semi-proportional majority-bonus system. The latter provides 50 seats to the party that wins the first place (no matter what percentage of the vote it had won) in order to guarantee the formation of governments with a “super-majority” in parliament. According to the Constitution of 1974, changes in the electoral system don’t apply immediately. Only after a new election takes place (held under the previous system), the new system can be put into effect for the one that will follow.

So, the elections of 2019 were held under the pre-existing semi-proportional system. They were won by New Democracy under Kyriakos Mitsotakis, which gathered 39.85 percent of the vote and secured a parliamentary majority with 158 seats out of 300.

SYRIZA under Alexis Tsipras was defeated by ND, but retained a significant part of its electoral strength, winning 31.53 percent of the vote and 86 seats. Once in power, one of the first acts of Mitsotakis was to change the electoral system again, reinstating the majority-bonus system with the explicit goal of enabling the formation of powerful single-party governments.

The new elections on June 25th will be held under this semi-proportional system, since the electoral results of May 21st (held under the proportional system) didn’t provide a parliamentary majority to any single party and there was no effort to form a coalition government.

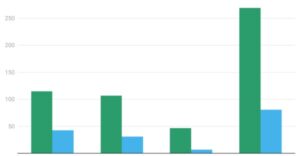

Mitsotakis led the Right to a clear victory, winning 40.79 percent of the vote and 146 seats, recording a 0.94 percent growth in its share of the vote. This level of support for the Right is not unprecedented in Greece and can be explained (as we will discuss later on this article). The electoral results were a political shock: not as much because of the reaffirmation of Mitsotakis’ political power, but rather because of the electoral collapse of SYRIZA: The party of Alexis Tsipras, who marched to the polls full of triumphalism, won only 20.07 percent of the vote, losing 11.46 percent from the last election in 2019. Acting as the opposition for 4 years, facing a repulsive government that frequently came into conflict with the majority of society and was rocked by successive scandals (like secret spying on the private communications of friends and foes of the prime minister), SYRIZA had managed to lose 1/3 of its electoral support!

If one doesn’t try to address and interpret these two sides of the result combined together, they will fail to grasp the meaning of May 21st, which many have labeled as a political earthquake.

New Democracy won 40.79 percent out of the 61 percent of eligible voters that went to the polls, and not the whole population. This means that its policy was “approved” (taking into account the inherent distortions of measuring “policy approvals” through the ballot box) by 30 percent of the population. This is a significant victory, but not a political triumph.

The explanation of this victory lies mostly in the field of the economy. Greek capitalism had a successful “rebound” after the pandemic (higher than the EU average). The average rate of growth in the profitability of the biggest 150 Business Groups in Greece in 2022 was 35 percent bigger than the growth rate in 2021, which was itself a high record. In this total, certain “champions” stand out.

The Vardinoyannis family, which controls (among many other assets…) the large refinery of Motor-Oil in the city of Corinth, saw its profits from refining, selling, and exporting fuels grow by 330 percent within a year! The Latsis family, which controls (also, among many other assets…) the once public large refinery of Greek Oil (ELPE), saw its profits grow by 160 percent in comparison with its high profitability in 2021. Shipping businesses, energy, tourism, construction, logistics, the food industry (production and sale) are among other the sectors that lead this race of growth.

This “business community” always has the capability to influence, align and lead the affluent middle classes and pull along broader sectors of society. The electoral victory of Mitsotakis was underpinned by the mobilization of the so-called “victors of the market”, based on the fact that the ruling class rallied around him politically and electorally. This can be seen not only in the numbers of the electoral result but mostly on the dominant features of the political discussion during the pre-election period: The ruling class (in control of all the “major” media) “forbid” any threatening subject that would go beyond the sole “management” of the status quo and that could give a broader anti-establishment dynamic in the demand “Mitsotakis out!”.

This alignment of the ruling class didn’t happen smoothly. During moments that the government was stumbling (e.g. after the revelations about the secret spying in communications, but even more so after the deadly train crash at Tempi), there were some powerful voices on behalf of Greek oligarchs that urged for preparations for multi-party governments of “broader consensus”, in case the electoral result would make this option necessary. But, as it turns out, this was a “plan B”, while the capitalist priority was support for Mitsotakis.

It is not that hard to answer why this was the case. At the time of writing, the Greek “heavy industry” of tourism is “opening for business”. Thousands of seasonal workers who work in these modern-day “galleys” are called to sing their annual contracts. According to reports, they are forced to accept a “penalty” (10,000 euros!) if they decide to leave their unbearable job before the end of the tourist season (in order to avoid the “great resignation” that started last summer…). They are also forced to adhere to a “confidentiality clause” (the violation costs a 5,000 euros penalty), so that the lousy and illegal daily wages that exist in the “tourist heavens” remain a secret.

During the first 4 months of 2023, there were 71 “accidents” in the workplace, with at least one worker dead. If this trend continues over the year, it will be a dark record in the history of Greek capitalism. Growth and the rise of profitability for businesses is achieved in a bloody way. And this way to growth is served by Mitsotakis in a coherent manner, without ideological reservations and with no hesitations.

So, there is no questioning why the upper part of society (the “privileged” 1/3 as we used to say) rallied with Mitsotakis. The question is why the bottom side, the 2/3 majority of society, didn’t find a way to rally politically and react electorally against this extremely neoliberal government.

Let me answer directly: The elections were not won by Mitsotakis but lost by Tsipras. The main donor to the electoral victory of the Right was the politics and the lousy electoral tactics of SYRIZA.

Tsipras gave this critical battle having at the core of his strategy the “smart idea” of shifting towards the political center, seeking for the votes of the middle class. As a consequence of this conservative shift, he didn’t make any convincing commitments to the interests of workers, farmers, the poor, while he avoided like the plague any edge that could be interpreted as a threat to “growth”, to capitalists, to amassed wealth.

Promising “win-win” solutions, that would supposedly make everyone happy, he tried to compete with Mitsotakis on a personal level, in the field of “best suited for office”, meaning the management of the status quo. His electoral campaign was a “one man show”, disappearing his party (supposedly in the name of a disciplined concentration of electoral firepower), withdrawing from public eye any symbol, feature, color or label that could refer to the Left. In order to highlight this shift towards the center, he “opened” SYRIZA’s ballot list to include “independent” personalities, retired army officers, celebrities of lifestyle journalism, politically failed social-democrats, and some politically “unemployed” politicians of the historical Right! On the pivotal question of what type of government he seeks to form, Tsipras’ answers displayed a phenomenal political confusion: He started the electoral campaign of SYRIZA proposing a “democratic-progressive” government (effectively a coalition with PASOK). He went on declaring that “we shall not form a government of the defeated” (meaning that SYRIZA winning the first place was now a precondition for “change”). He later switched to asking for a “convergence” with PASOK, MERA25 and the Communist Party (after trying to diminish them electorally), before ending up declaring that he is open to a politically unspecified governmental “solution” of broader consensus.

All these combined ended up highlighting the major problem of credibility, one that follows SYRIZA ever since the betrayal of people’s hopes and expectations in 2015. The website in.gr (owned by oligarch Vagelis Marinakis) put it this way: “Tsipras will not grasp the meaning of what happened in 2023, because he hasn’t grasped the meaning of what he did in 2015”.

The end result was a crushing defeat for SYRIZA. The party lost even in sectors that it considered as “bulwarks” of electoral support, like the poor working-class districts in Athens and Piraeus or among the youth (voters 17-24 years old). New Democracy remained in second place only among workers employed in the private sector. When compared with the elections of January 2015 (the peak of the electoral support for the Left), SYRIZA has subsequently lost the vote of 1,500,000 people!

The culmination of SYRIZA’s social-liberal mutation, the hype around Tsipras’ warm relations with the leaders of European Social-democracy, Tsipras’ efforts to appropriate the tradition, the slogans, even the personal style of Andreas Papandreou, had as an effect the reinforcement of PASOK! Under the new leadership of Nikos Androulakis (who also rallied around him some of the experienced “barons” of PASOK’s golden era), the original social democrats raised their electoral support by 3.35 percent, reaching 11.36 percent and securing a double-digit score for the first time since 2012, when the rise of the radical back then SYRIZA started and eventually sunk them into irrelevance in 2015. In 6 electoral constituencies, PASOK overtook the second place from SYRIZA, which could display a potential jump-start of a new political process, where the power ranking among the opposition will be at stake.

The Communist Party raised its support by 1.93 percent, reaching 7.23 percent and winning 426,000 votes. This is a piece of good news, because it reflects the resilience of a section of the working class and the popular layers against both the neoliberal attack of Mitsotakis and the conservative shift of SYRIZA. But this strengthening of the Communist Party, when compared with the 600,000 votes that the Party used to win in elections before the crisis, and most importantly with the potential that emerged by the masses of people that withdrew their confidence from SYRIZA, it is proven to be a limited growth, smaller than the objective potential. One should seek for an explanation to the sectarian policy of the CP and the consistent tactic of its leadership to avoid the political responsibilities that correspond to the Party’s organizational strength.

“MERA25-Alliance for Rupture”, led by Yanis Varoufakis and joined by an important part of the older formation of Popular Unity, won 155,000 votes and 2.63 percent of the vote, failing to pass the 3 percent threshold to enter the parliament. It paid the price of the contradictions related to the leading role of Yanis Varoufakis, who didn’t succeed in convincing a wider left-wing audience to support them, despite the potential generated by SYRIZA’s losses. We hope that this result can be “corrected” on June 25th so that MERA25 brings an additional force of left-wing opposition in parliament.

The largest among the various electoral lists of the far-left, ANTARSYA, was limited to a result that simply puts its presence on record, winning 31,746 votes and 0.54 percent of the vote. It has a marginal growth by 0.13%, which cannot be considered as satisfactory, neither in absolute terms, nor in relation to the thousands and thousands of people who disengaged from SYRIZA’s support. ANTARSYA has tried this type of electoral intervention repeatedly over the past 15 years, without ever achieving a different result.

In the menacing current of the far-right, Greek Solution, the nationalist-racist party of Kyriakos Velopoulos entered parliament, winning 4.45 percent, 262,000 votes and 16 seats. There was also a new entry in this side of the spectrum, a party called Niki (Victory), which marginally failed to enter parliament, after winning 2.92 percent and 172,000 votes. It is a party of ultra-conservative Christian Orthodox parachurch organizations, which is financed by some major monasteries of the Monastic Community of Mount Athos and admires the “Orthodox brethren” of Russia under Putin.

As an aggregate, the forces of the Greek far-right remain a dangerous foe, although they are far from the appeal and most importantly the street force that the Neonazis of Golden Dawn had managed to build during their heyday. The dismantling of Golden Dawn, this major achievement of the antifascist-antiracist movement, remains a “guide” to confront this ultra-reactionary and menacing political current.

Trying to interpret this new political landscape, some analysts are led to theories about a generalized “conservatization” of Greek society. Such easy generalizations have a questionable value for sociologists and journalists, but nothing creative for activists on the social movements and the Left. These theories are not confirmed as valid if one takes into account all aspects of social reality.

The actual class balance of forces, the political balance of forces and the electoral balance of forces are different quantities and qualities to measure. They are interrelated and they influence each other, but they are not identical.

A few weeks before the May 21st election, after the train crash at Tempi, over 2.5 million people participated in a succession of strikes and protests. Research institutes affiliated to trade-unions, but also (mainstream) poll companies, agree on the estimate that this was a peak of expressed working class and popular anger, that can be compared only with the militant mood that prevailed in the stormy period of 2010-13. This force didn’t emerge out of the blue skies. Neither did it evaporate into nothingness. The defeat of the Left in the May elections should and could be explained by the choices made by the political parties, and especially SYRIZA, when trying to express this force in terms of political tactics and electoral choices. As far as we are concerned, we insist that the sight of strikers and protestors last March in Greece retain a decisive political importance and should not be forgotten because of the adverse electoral results in the ballot boxes.

The result of May foreshadows, to a certain extent, the result of the next election on June 25th.

Unless some disruptive surprises occur (not foreseen for now), Mitsotakis will win a parliamentary majority for a new single-party government. There is no doubt that such a government will be aggressive, fully committed to capitalist greed. But it is worth noting that the end of fiscal “relaxation” and the restart of the obligation to debt repayments mark 2024 as a crucial turning point for Greek capitalism.

The European Commission already informed the next government (and the public) that according to the 2018 deal between Greece and the creditors and the “midterm” evaluations of Greek economy, the electoral promise of Mitsotakis to raise the average workers wage (by abolishing the freeze that was imposed on “wage maturation/progression” during the Memorandum) should be considered out of the question. Thus, one should not underestimate the fact that there are voices in the mainstream Press that insist on the need for “broader consensus”, despite the electoral victory of Mitsotakis.

In SYRIZA, the question that will be posed is whether it will retain an hegemonic place in the ranks of the opposition. The reflexive reactions of Tsipras after the result were worse than his electoral tactics. When the Central Committee of SYRIZA convened to “inspect” the reasons of the crushing defeat, members of the CC were not allowed to make contributions and speak, instead they were confined to listening a very long speech by the Leader. This degeneration of the party, that could make a hard-core Stalinist blush, could never produce something decent: Tsipras declared that “he shall remain at the helm of the party” and he put the blame for the defeat on… proportional representation and the mistakes of PASOK, the Communist Party and MERA25, for refusing to acknowledge his decisive role in the “change” he was pursuing.

PASOK will seek to shrink the electoral gap between itself and SYRIZA. A process of “social-democratic recomposition” involving PASOK and SYRIZA (a project with some serious supporters inside both parties), will have to proceed at a slower pace and in the context of a new balance of power between the two parties.

The size of a left-wing opposition in parliament will be determined by the scale of the electoral strength the Communist Party will eventually record and by the question of whether MERA25 will enter parliament or not.

In the coming period, the most dangerous enemy for Mitsotakis will be action “from below and from the left”. The confrontation with this adversary will determine the resilience and eventually the viability of the government that will emerge after the polls on June 25th.