This article was translated into English by Panos Petrou.

Victory for the right, strengthening of the far right and the end of an era for Alexis Tsipras’ SYRIZA

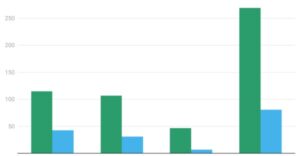

The June 25 elections in Greece confirmed, but also reinforced, the harsh negative features of the results of the “first round” of the May 21 election. In the new parliament, the sum of the right and the far-right parties reached 200 seats (out of a total of 300), thus creating a correlation of parliamentary forces that is unprecedented in the years following the overthrow of the military dictatorship in 1974.

It is impossible to interpret these results politically without taking into account the huge increase in abstention: in the June 25 elections, turnout was reduced to 52.8 percent, a historic low. Political lived experience can further illuminate the message of these numbers: the June 25 elections were the most “silent”, the most “from above” elections I have witnessed since the fall of the military junta. Every habit, symbol, color (big election rallies, local meetings and events, campaigning tours in workplaces, posters, flags, etc.) that would suggest the involvement of the masses was systematically avoided by all parties (with the exception of the Communist Party). It was a choice made by the parties, especially the main opposition, which played into Mitsotakis’ hands. In the elections of June 25, it was mainly the working and popular masses who withdrew their hopes of improving their lives through the electoral process: the swollen abstention was the result of the disillusionment and disaffection of our social camp.

Victory of the Right

In these circumstances, Mitsotakis’ New Democracy recorded a clear political victory. They won a comfortable parliamentary majority of 158 seats, which enables them to form a new single-party government. It is worth remembering that Mitsotakis made no secret—even during the period of pre-election demagoguery—that if he regained governmental power, his program would consist of a quantitative and qualitative acceleration of anti-worker, anti-social “reforms”. This is already reflected in the provocative composition of the new government, announced the day after the elections: It is composed of members of the extreme neoliberal wing of the Right, of “technocrats” who enjoy the direct confidence of the Greek capitalists, of veterans of social liberalism who have long since moved from the “modernizing” Blairite wing of PASOK to New Democracy. The determined effort for hard privatization in public education (with measures inspired by the policies of Margaret Thatcher) and the sweeping privatization in public health are decisions that have already been foreshadowed.

However, some remarks are necessary to relativize Mitsotakis’ triumphal image. a) New Democracy won 40.55 percent out of the 52.8 percent that took part in the elections, i.e. it got the “political approval” of a part of less than 30 percent of the actual population. This is the “privileged one-third of society” (ruling class, affluent middle classes, upper state officials, including their electoral influence), whose close relationship with the right-wing party is not a surprising phenomenon in Greece. The crucial question in the interpretation of the election results (and in the post-election developments) is what happened and what is happening to the remaining “underprivileged two-thirds of society”. b) It is a common secret in Greek political life that this part of the “two-thirds” has not been crushed, has not given up the militant defense of its interests. A few weeks before the elections, immediately after the tragic railway “accident” in Tempi, the strike rallies and demonstrations took on such a dimension and intensity that led Mitsotakis to a frightened search for a defensive folding. This force did not come out of nowhere, nor was it lost in the void. It is likely that it will manifest itself post-election (e.g. in public hospitals, schools…) bringing back on stage the real opponent of Mitsotakis. c) The prospects of Greek capitalism are not rosy. The governor of the Bank of Greece, Yannis Stournaras, chose to declare publicly a few days before the June 25 election that the end of “quantitative easing” and the return of fiscal discipline and debt repayment obligations constitute a particularly dangerous juncture.

All these factors together explain Mitsotakis’ attempt to prevent his cadres from celebrating and showing off arrogance. The extremely pro-government newspaper “Kathimerini” chose to warn New Democracy that “the second four-year term may turn out to be a curse”.

Strengthening of the far right

What makes the sense of the electoral results even more bitter is the strengthening of the far right.

In the June 25 elections, three far-right parties crossed the 3 percent threshold and entered parliament with a total vote of close to 12 percent. In addition to the ultra-nationalists of Kyriakos Velopoulos’ “Greek Solution”, both the religious ultra-reactionaries of the “Victory” party and the hidden neo-Nazi “Spartans” party—linked to the imprisoned former deputy leader of Golden Dawn, Ilias Kasidiaris—entered the parliament.

This political current is currently reaping the fruits of the international trend of an emboldened far-right. It is also reinforced by the racist-sexist aspects of governmental policies and the state institutions. But it is also reinforced by the Left’s concession to critical points of the nationalist agenda (armaments, Greek-Turkish competition in the Aegean, etc.) and to the racist state policies. The “fence” on the Greek-Turkish border in Evros against refugees and migrants was a central political point of conflict during the election period. The statement of Aléxis Tsípras that “the fence has already been built and now it stands as it is” was raising a white flag facing Mitsotakis, but it also signaled the disorderly retreat of SYRIZA from the tasks against racists. A few days later, the tragic shipwreck in Pylos with hundreds of drowned refugees after the criminal handling of the Greek Coast Guard highlighted the dramatic and disturbing problems in this policy.

In Greece, the far-right has not yet “recovered” from the defeat of the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn and its dissolution as a “criminal organization”. But there is no room for underestimating the danger: the far-right racists, and especially the hidden neo-Nazi Spartans, will now have the political opportunities and the material resources that their entry into Parliament brings. The antifascist-antiracist and antisexist movements will have before them as their main task to block any possibility of the far-right to make extra steps in its growth, and in particular block them from making the crucial step of rebuilding a violent force in the streets.

End of an era for Tsipras’ SYRIZA

A key issue in the 2023 elections was the electoral crushing of Alexis Tsipras.

In the elections of June 25, SYRIZA garnered only 928,000 votes and 17.8 percent of the vote, losing 250,000 votes from its low performance on May 21 (1,185,000 votes and 20.07 percent). If we compare this result with SYRIZA’s electoral influence at the dawn of this turbulent political period and SYRIZA’s electoral victory in January 2015 (2,245,000 votes), the stark realization emerges that more than 1.3 million people—mostly workers and the poor—who had pinned their hopes on Tsipras have gradually withdrawn their trust!

This picture of electoral collapse is the result of a long political mutation. In the political and electoral defeat of 2023, SYRIZA paid bills it owed from the past: the betrayal of workers’ and people’s hopes in 2015, the neoliberal policy of the Tsipras government in 2015-19, the miserable agreement with the creditors in 2018, falsely called “exit from the memoranda”, while actually perpetuating all the past anti-labor memorandum “regulations” until 2060, the deeply consensual and “respectable” opposition to Mitsotakis after 2019. But it also paid the price of the absolutely wrong right-wing policy it deployed towards the election: the “widening” of SYRIZA towards the political center, the appeal and the reference to the middle classes, the identification with European social democracy, the vaporization of the party and the absolute supreme-leader role of Tsipras, the minimal and contradictory commitments towards the demands of the workers and the poor, etc. The result was an electoral crushing defeat that constitutes above all a heavy political defeat.

A side effect of Tsipras’ social-liberal turn was the strengthening of… PASOK. Under the new leadership of Nikos Androulakis, taking advantage of Tsipras’ ideological and political retreat, PASOK won on June 25 617,000 votes and 11.85 percent of the vote. It thus returned to a level of influence that gives it prospects for some dynamic role in politics, after the era of complete marginalization imposed by the rise of the radical SYRIZA between 2011 and 2015. PASOK’s gains are small compared to SYRIZA’s losses, proving that the “comeback” of the original social democrats is proceeding “at a snail’s pace”. But they have already established that the prospect of a social-democratic recomposition (involving the two parties) is no longer a case of a “protagonist” and an “extra”. The pressures that this development was putting on the Syriza leadership were crushing.

On the evening of June 25, Alexis Tsipras announced his intention to remain as party leader and to define “changes” towards an even broader “enlargement” and an even more leader-centered party. His supporters (especially strengthened within the now smaller parliamentary group of SYRIZA) were leaking to the press plans to change the name of the party so that it would no longer include the word “Left”, change the party’s structures to remove anything that still might resemble the radical past, officially transfer SYRIZA to the Social-democratic Group in the European Parliament etc.

This direction did not last even three days. On June 29 Tsipras announced in a televised address that he was resigning “with bravery”, in order to leave the way open for “a new wave of renewal of SYRIZA”. Characteristic of the “bravery” of this self-evident decision is that earlier Tsipras had announced it only to a certain “Executive Bureau” of SYRIZA (an informal body of friends and associates that he himself has set up), avoiding even to convene the statutory governing bodies of SYRIZA (Political Secretariat and Central Committee), that will be called upon afterwards to manage this crisis situation.

The interpretation of this development is simple: On the one hand, SYRIZA’s defeat is heavy. In Parliament, it will find itself with a small parliamentary group against a strengthened Mitsotakis. On the other hand, SYRIZA’s internal situation is now a boiling pot. On election night, two former general secretaries of the party (Panagiotis Rigas and Dimitris Tzanakopoulos), disagreeing on the causes of the electoral collapse, instead of exchanging arguments, they ended up exchanging blows and flying chairs and then the incident was leaked to the Press and later confirmed. If this is the atmosphere at party headquarters, it is easy to imagine what is happening in the relationship with the organized members.

At the time of writing no one can speak with any confidence in prospects. Tsipras’ heavy dominant leading role had left no room for some younger cadres to emerge who could take on the crucial task of forming an alternative leadership. SYRIZA’s crisis is so deep that only a serious and convincing “left turn”, in conflict with all the fait accompli of the last few years, could (with many doubts of success) set a reconstruction process as a viable goal. In both of these areas (new leadership and new political direction), at least at the moment, there seems to be no elementarily credible solution.

Despite the magnitude of the defeat in the 2023 elections, the big downhill is ahead rather than behind for Alexis Tsipras’ party.

Alternative?

The great losses of SYRIZA have not been won over in support for any of the parties on its left.

The Communist Party recorded a modest growth, reaching 400,000 votes and 7.7 percent. But when compared both to the electoral performances of the CP until 2012, and to the size of Syriza’s losses, this step forward cannot be called satisfactory. The Communist Party has once again paid the price for not assuming major political responsibilities, for stubbornly refusing any unity of action aimed at fighting for concrete victories for our people here and now, for having chosen its own “snail’s pace” of its own slow parliamentary reinforcement.

The MERA25 ballot of Yanis Varoufakis, joined by the remaining Popular Unity within the “Alliance for Rupture”, narrowly failed to enter the Parliament, staying at 2.5 percent. Between May and June, it lost 25,000 votes that if it had held on to, it would have entered parliament (due to increased abstention). It thus paid mainly for the ambiguities of Varoufakis’s interventions during the election period.

The coalition group of the anti-capitalist left, ANTARSYA, in the May elections got 31,7000 votes and 0.54 percent of the vote. It estimated at the time that this was “a small but important” step of reconstruction. But in the June elections ANTARSYA was reduced to 15,900 votes and 0.31 percent, which displays a rather loose and superficial link even with this limited base of support.

A section of the radical anti-capitalist left chose not to stand in the elections, to call for votes for parties of the left beyond SYRIZA and to emphasize the need for united front action in this difficult period. This section, in the new post-electoral conditions, will have to support new beginnings, without any sectarian division towards those who have tried different electoral tactics, and with a focus on the struggles that Mitsotakis will inevitably find himself facing again.

This is also the tactic of the Internationalist Workers’ Left (DEA).