This article first appeared as a document in ISO preconvention bulletin #43, February, 2019. It more or less accurately predicts that the then-current trajectory of the ISO could lead to its liquidation into the DSA/Democratic Party. Though the ISO collapsed before this outcome came about, a month after this article was written the ISO national convention voted to incorporate into its leadership several supporters of Bernie Sanders, and approved a “special convention” to discuss whether or not to endorse his presidential bid. Dozens of individuals who won leadership at the ISO convention and facilitated its dissolution have since abandoned revolutionary politics and joined the Democratic Socialists of America.

“As someone who has been active in socialist politics for more than 20 years, I have participated in several heated debates over issues concerning electoral politics. In each instance, the debate centered on whether and to what extent it was appropriate for socialists to work for candidates running within the Democratic Party. Each time those whom I debated were convinced that their support for a specific candidate represented a strictly tactical response to the exceptional circumstances of that particular election. They further insisted that they remained critical of both of the establishment parties and, in general, that they were still revolutionaries who believed in grass-roots militancy as the only path toward socialist transformation. Despite these protestations, in each case the decision to back certain liberal Democrats soon led to a fundamental shift in strategic perspective. Indeed, each of these sets of socialists became fervent advocates of strengthening the broad liberal coalition within the Democratic Party, and they proceeded to chastise those of us who presented alternative strategies for being ultra-left sectarians.” — Eric Chester, Socialists and the Ballot Box

I want to make three key points in this document.

First, to briefly restate the centrality of the principle of class independence and the operational position which flows from this—no support for candidates of the two main bourgeois parties. A significant number of our members who now back Sanders, et. al., while insisting that they accept the principle of class independence and consider working inside the Democratic party to be merely a strategic detour that will lead in the future toward independence, are in fact abandoning the principle of class independence, regardless of their beliefs or intentions.

There is, however, also a much larger layer of members, including a significant portion of the current ISO leadership, who accepts the self-identification of the pro-ballot line minority as having only strategic differences with the ISO’s stand on the Democrats. This layer is “not convinced” that it is a strategy we should adopt, and attack as sectarian those who hold the position that the ballot-liners are departing from principles. Sanders’ supporters in the ISO are, says this grouping, revolutionaries who seek the same goal via a different path. This grouping, in addition, wants to treat self-identified socialist congress members like Tlaib and Ocasio-Cortez as if they are a kind of socialist trojan horse working for “our” side whom we consider to be our allies and comrades in congress. This second position represents an accommodation toward the ballot-line position.

The reduction of principled differences to strategic differences has organizational implications for the ISO. If both supporters and opponents of supporting Democratic Party candidates in the ISO have merely strategic differences, then a logical conclusion is that the ISO should make room (or, in current parlance, be “open”) to including in its ranks both proponents and opponents of supporting socialists running inside the Democratic Party. If this step is taken, then the ISO will cease to be a revolutionary organization found on the key principles outlined in the Where We Stand and become something else: a more “plural” organization whose boundaries are widened to include those who are willing to engage in tactics that undermine the project of building working-class political independence along with those who remain committed to it. As such, it will become increasingly indistinguishable from a “broad tent” organization like the DSA. If this happens, the ISO can no longer consider itself to be a revolutionary pole of attraction on the left, let alone within a larger socialist party were we to enter or build one.

We should openly and clearly air all of our differences, and shades of differences, as fully and clearly as possible, and as comradely as possible—as many documents have noted. This can only be to our benefit. But we should not confuse free and open debate with what Lenin referred to as “freedom of opinion,” which is not the same thing. The former helps us clarify our views. The latter involves tolerance of differences. As Lenin noted in 1899, as he was attempting to unite the disparate local organizations into a single Russian socialist party, full discussion and debate was necessary in order to gain clarity on the programmatic differences in the movement: “The polemic will be of benefit only if it makes clear in what the differences actually consist, how profound they are, whether they are differences of substance or differences on partial questions, whether or not these differences interfere with common work in the ranks of one and the same party.”

Why principles matter

A number of documents by Lance S., Keith R., Megan B., Alessandro T., and others have not only made strong cases that we reject support for socialists running as Democrats, but also that it is one that involves basic principles and not merely competing strategies. The position has never been one that we simply state and consider settled. Where We Stand is a merely distillation of our points of unity, not the arguments as to why we hold to them.

In the runup to the 2017 ISO national convention, Danny K. wrote a document titled, “Why principles matter” in response the view among some ISO members at the time that, in his words, “our opposition to the Democratic Party isn’t in fact a matter of principle at all, but is purely strategic.” He took up the argument that it was “moralism” and reflective of “call out culture” to assert our principles on the Democratic Party. This is how he answered: “I imagine that some comrades who think it sounds moralistic to talk about our opposition to Democrats as a matter of principle might not mind talking about their ‘principled’ opposition to sexism or imperialism.”

Danny, in asserting the importance of principles, did not simply believe that our job as socialists was merely to walk around citing our principles:

We can’t win people to the politics of class independence simply by asserting it as a Marxist principle…. We’re…doing ourselves a disservice if we don’t explain or publicize that our strategies flow from a 150-year-old tradition of principles that have stood the test of time far better than our opponents. The decision not to endorse a left-wing Democrat wasn’t just a strategy we decided on this year—and by coincidence every other year it’s come up. To present our line in purely strategic terms deprives us and our audience of the larger context for understanding our position.

The fact that since Danny wrote these words the substantial growth of the DSA, and a Democratic Party shifting, at least in part, in a more liberal direction to absorb the growing forces of the left, makes these arguments more, not less, important.

Honest opportunism

Does this mean that the comrades who call for supporting Bernie Sanders are insincere when they say that they consider themselves to be upholding the principle of class independence? Not at all. They are all, to my knowledge, sincere. But we do not judge a political position based on what claims are made for it. One does not prove a commitment to “the principle of class independence” simply by repeating the phrase over and over again. The question is: do socialists running on Democratic Party ballot lines, or supporting candidates like Bernie Sanders, AOC and Tlaib reinforce class independence or class subservience to the Democratic Party? If the latter, then as a “strategy” it violates the principle of working-class independence, and therefore, whatever claims are made for it, or the intentions of its promoters, it constitutes a strategy toward a quite different goal.

Rarely in the history of the Marxist movement has a departure from a central tenet of Marxism in the movement been presented as a theoretical or principled departure. More often it is presented as an innovation, a fresh application of our politics to new circumstances. Those who disagree and hold to “tradition” are painted as “dogmatic,” uncritically clinging to old, outmoded formulas. Defense of a central tenet is depicted by the advocates of the new as hindering our “freedom” to explore, to be critical, and so on.

Many comrades are making a similar set of arguments today to back their support for Sanders and the ballot line. Their argument is that we live in an unprecedented moment in which it is possible to build a socialist movement that operates both outside and inside the party, and that this strategy will prepare us (and these candidates, apparently despite their own currently-held views) for a future break out of which will come an independent socialist or Left party. They insist that they remain revolutionaries, but that extraordinary and unexpectedly new developments—the growth of DSA, the popularity of Sanders—requires us to enter the Sanders campaign, and that not to do so would be sectarian and put us on the sidelines of the new socialist movement. They are fully aware of the risks of operating inside the Democratic Party, but also argue that the benefits of being inside outweigh the risks.

This approach sacrifices the future of working-class independence for the sake of short-term political gains that actually works against that future. It is not a question of doubting the sincerity of these comrades. What is at issue is what their politics actually mean in practice: the subordination of the working class to bourgeois politics in the name of independent politics. Engels was not wrong when he wrote in a different context:

This forgetting of the great, the principal considerations for the momentary interests of the day, this struggling and striving for the success of the moment regardless of later consequences, this sacrifice of the future of the movement for its present, may be “honestly” meant, but it is and remains opportunism, and “honest” opportunism is perhaps the most dangerous of all![1]

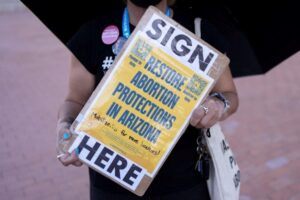

It reveals either an unconscious or willful lack of historical insight to claim, as Hadas T. and Dorian B. do, that the Left that enters the Democratic Party can only be coopted by it in a period of movement decline, and that it is possible to avoid this in a period of rising class struggle. Their own shift in political outlook proves otherwise. The examples of the absorption and destruction of the Populist Party in 1896, and the deliberate derailing of a labor party in the 1930s, which had widespread support among workers at the height of the class struggle, through the creation of fake, nominally independent labor nonpartisan leagues, are just two examples of periods of rising struggle where the Democrats successfully coopted Left and third-party initiatives. And in the 1930s it was done with the assistance of the largest party on the Left, the Communist Party.

Independence from the Democratic Party is an absolute precondition for the creation, in any form, of working-class politics that is able to free itself from subordination to capitalist parties in the US. The formation, and success, of such an independent political party, capable of running its own candidates that challenged the two-party status quo, would represent a tremendous advance in the US context. But such a party cannot be built so long as the left allows itself, in the name of practical expedients and “realism,” to be lured into the Democratic Party.

In this regard, Marx and Engels 1879 circular skewering a group of German socialists who wished to convert the party into one of mild social reform and to look to the “possible,” makes a highly relevant point. These socialists argued that the party “concentrate our whole strength, our entire energies, on the attainment of certain immediate objectives which must in any case be won before there can be any thought of realizing more ambitious aspirations.” To this, Marx and Engels replied: “The program is not to be relinquished, but merely postponed — for some unspecified period.”

Staking a middle ground

As already noted, there is a substantial layer of members, including members of the SC majority and of the NC, who accept many of the arguments made by the pro-Sanders group within the ISO. Though they currently do not support the ballot line position (the current popular phrase is that they “are not convinced”), they insist repeatedly that the difference between supporting and not supporting socialists on Democratic Party Ballot lines is a difference over strategy not principle. Their interventions in the current debate spend very little time making a case against endorsing Sanders and the ballot line, and instead direct most of their criticism at those who want to maintain ISO’s principled stand on the Democratic Party. They propose that we postpone a decision whether or not to endorse Sanders in 2020 to a special convention, despite the fact that the ISO has had months of debate on this question and had a clear and effective position in 2016. Alan Maass writes in his document on US politics, for example:

I’m not convinced that we should change our position on the ballot line strategy or supporting Democratic candidates. I am persuaded that this discussion shouldn’t be concluded before it is had out, nor before we see more of how the 2020 election period takes shape.

Some have argued clearly, on paper and in debate forums like the NBC call, that our differences on the Democratic Party within the ISO are differences between revolutionaries over how to strategically get to an agreed-upon goal. Natalia T., for example, writes in Bulletin #3 that “Comrades on all sides of the debate agree that the objective is to become strong enough to oppose the Democratic Party from outside of it. There is a continuum of arguments about how to go about this strategically.” This position has been repeated in various debate venues by others.

Todd C., going one step further, posted a FB response to my article last October on the Philadelphia District Attorney in which he wrote that “I am still not convinced supporting campaigns within the limits of the Democratic Party makes sense”—the “still” implying that he is weighing the question before he makes a final determination.

Jen R., on the other hand, in her polemic with Lance Self in Bulletin #11, begins by apparently agreeing with Lance:

I agree with the principle that the working class must have its own political representation independent of capitalist parties. I also agree that in this country this principle is operationalized as opposition to the Democratic Party as a capitalist party. I have not been convinced that socialists can attempt to use the Democratic Party in order to advance a path towards independence through strategic use of its ballot without necessarily sacrificing its principles and class independence.

Some members of the ISO today claim to “use the Democratic party to advance a path toward independence.” According to Jen, this position will actually sacrifice the principle of class independence—the same argument Lance, I, and others have been advancing. And yet, after this good, albeit somewhat equivocal statement (“I have not been convinced”) of our standard views on the question, she negates everything she has just written: “Is Lance seriously arguing that comrades who have spent 15, 20 or 30 years building a revolutionary organization have suddenly developed a difference in principles?”

I am not in a position to assess how gradually or suddenly these differences developed. The unfortunate truth, however, is that the history of our movement is full of people who traversed this terrain. If it is possible for people who are radicalizing to move from illusions in electing better Democrats to becoming revolutionary socialists, the opposite path is also possible—and not uncommon in the history of the Left. A whole layer of revolutionaries who in the late 60s and early 70s became committed to overthrowing capitalism ended up in union administrations and the Democratic Party.

One has only to read Alan Wald’s The New York Intellectuals to see this: Max Schachtman, Sidney Hook, Max Eastman, and Irving Howe, all began as revolutionaries and ended up as right-wing, pro-Democratic Party social democrats. Wald writes that Irving Howe, like many others, went from being a Trotskyist in the Young People’s Socialist League who supported neither Washington nor Moscow, to becoming an “ethical” socialist whose definition of “democratic socialism” included a defense of Western “democracy” against Stalinist “totalitarianism.”

Over the years the call for this ethical socialism was replaced by the demand “to extend the welfare state,” and eventually Howe, like Hook, came to identify true socialism as being essentially a militant wing of liberalism. This shift was facilitated by the vagueness of the term “democratic socialism,” to which Howe was able to attribute a different political content at each phase of his development.

Our “comrades” in Congress?

Our position regarding the Democratic Party—that it is one of the two parties of US capitalism, and hence also a party of imperialism—has never been based on the argument that these parties are identical. On the contrary, we have always argued that the Democratic Party, broadly speaking, is the more liberal party, and that historically it has, when necessary, shifted its language, and its policies, in order to absorb and contain the discontent of the exploited and oppressed; to confine it within the boundaries of capitalism, and to prevent the formation of viable labor and left third-party alternatives. Throughout much of the ISO’s history, it has been a rightward-moving, neoliberal party. Most of our members have joined in this period.

But we always understood that it was capable of adaptation (as in the 1930s and the 1960s) given rising struggle and discontent, in order to attract and absorb oppositional movements and campaigns. The reality is, that even in its neoliberal phase the party has shown its capacity to adapt. The party remains a staunchly, center-liberal party, but it has always had a layer of officials who are able to extend their influence into the ranks of trade unionists and social-movement activists, who have protested, gotten arrested even, and attempted in other ways to associate themselves with social movements.

We often talk of the gravitational pull of the Democratic Party, but we sometimes forget that it is organizations and individuals that are the agents of that process. We also forget sometimes how this process works. The Democratic Party could not have had such success in demobilizing and absorbing forces to its left—the populists and the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party, sections of the Civil Rights movement leaders, and even of the revolutionary left, for example—if it were not a highly adaptable party that knew well how to maintain and nourish, a progressive, left tail. This fact perhaps was more hidden as a result of the party’s adaptation to neoliberalism, but this tail (as any activist in a major city knows) has always existed. As we well know, the tail does not wag the large and powerful dog. Whoever grabs the tail gets dragged by the dog, even though they sincerely believe they are doing something else.

Tlaib and AOC are the most radical members of congress and raise criticism of corporate control of the party. Both come from activist backgrounds and appealed to that background as part of their campaigns—that real change couldn’t come without movement support. Both also were involved in Democratic Party politics well before their congressional runs. Their election is an extremely positive development, showing that political conditions are creating an opening for socialism, however vaguely defined, and that there is dissatisfaction with the Democratic Party’s pro-business centrism. But we should be cognizant of the other side of this picture—their role in fluffing up the party’s left tail.

While many seem to think the election of Tlaib and AOC represents something entirely new, this isn’t true. The path from participation in radical social movements to Democratic Party politics has been tread many times and in many eras of US history. Those who have done it don’t see this path as selling out, but as a logical step in a process of trying to make a difference.

Take one example, Luis Gutierrez, who served as a US representative for US 4th Congressional district for Illinois from 1993 to 2019. As his Wikepedia entry states:

Of Puerto Rican descent, he is a former supporter of Puerto Rican independence, and the Vieques movement. Gutiérrez is also an outspoken advocate of workers’ rights, LGBT rights, gender equality, and other liberal and progressive causes.

I have personally seen Luis Guttierez deliver speeches that are every bit as radical as Tlaib or Ocasio-Cortez. Some comrades seem to think that AOC’s attendance at rallies and sit-ins is something new. It is not. Progressive and liberal Democrats have been doing it for a long time. Jesse Jackson has been attending protests, and getting arrested at them, for decades. Luis Gutierrez was arrested several times in protests and civil disobediences—in protests on the island of Vieques, PR, in protests and marches for amnesty for undocumented immigrants, and in defense of the Dream Act and other immigrant rights issues. His most recent arrests were in August and September of 2017 at the White House and at Trump Tower in Chicago.

That of course didn’t prevent him from being a strong backer of Chicago mayor Rahm Emmanuel and Hilary Clinton in her 2016 election bid. Being the consummate political maneuverer, his last act being an end of the wire announcement of his retirement in order to ensure a quick succession without challenge to allow Jesus Chuy Garcia to take his place.

The background, verbal radicalism, and progressive positions, of politicians like Gutierrez, Tlaib and AOC doesn’t alter (but in fact help explain) the objective role they have played in revitalizing the party’s image among activists. The idea that their work complements social movements rather than contradicts them is a common one in the long history of the relationship between activism, social movements, and the Democrat Party. We have continuously to have patient arguments with those who see no contradiction between engaging in struggle and voting for and supporting Democrats. The argument parallels the one put forward by DSA and some of our members, that AOC and Tlaib’s presence in congress as Democrats assists us in building the “new socialist movement.” Again, we have to argue that while their presence in Congress is a good sign, and that it helps raise the profile of socialism, we must also understand that they are helping to put a left face on a capitalist, imperialist party and derail the building of an independent socialist movement.

And yet, Candidates like AOC are now being openly discussed by some comrades as if they are our chosen representatives in Congress. Alex S. recently referred to “our democratic socialist representatives in congress” on a Facebook post. In a January 8 post, Todd C. argued that in the past “the Democratic Party has succeeded in bringing opposition to heel. The practices and organizations we develop, and our ability to rewrite the rules of the game will determine our movement’s fate.” The clear implication is that AOC might defy, with our help, the “rules of the game” and operate inside the party without lending illusions in it or being coopted by it.

In another thread, Todd C. weighs in on the question of how we hold various candidates like Ocasio-Cortez accountable, whom he refers to as “electeds,” writing of her as if she is our chosen representative in congress whom we can directly influence, work with, and make demands on, as a peer, and that this connection we develop with her will insulate her (and others like her—that is left wing Democrats) from the dangers of cooptation.

“We want to get to the point (in the coming years where electeds like AOC 1) know that once a month they have to attend organized party/community forums 2) socialist/organizers/coalitions should have a direct phone line to her office with designated liaisons,” he writes. These hypothetical liaisons will criticize her for mistakes, and ask her to join various delegations, support, publicize and speak at various actions, etc. Todd writes of not underestimating “the importance…of leading activists developing peer to peer relations with the electeds.” The “key dynamic,” he writes, “is creating a movement that refuses to accept the ‘insulation’ of the electeds from the movements, which includes elected realizing (which I personally think AOC understands) that the ‘insulation’ is not only a danger for the ‘base’ but also the electeds themselves.”

It isn’t clear how the ISO, let alone the DSA—which has no clear mechanism for holding the candidates they endorse accountable—would be able to make such demands on these politicians. How precisely does Todd propose that we create disciplined organizational ties in which socialists inside the Democratic Party are expected to attend meetings and phone calls in which we criticize, make demands, requests, etc. Doesn’t this imply conditions that don’t pertain to the example: These politicians are more disciplined by their own party, the Democrats, than by the left. We have always argued that struggle, public criticism, and demanding that politicians act according to their promises and stated intentions (insofar as we support them), is the way that movements exert influence on politicians of the Democratic Party. Now we are being told that we can not only have deeply collaborative relationships with left Democrats, but that we can establish organizational relations of accountability with them.

Some have even argued that we can only hold such “electeds” accountable if we are part of their campaigns, or, as Todd puts it, that we have “peer to peer relations” with them. This contradicts our political history of understanding social changes as developing from social movements, not personal connections, as a means to hold politicians accountable.

It is as if, in the words of another poster on this thread, James Hoff, Ocasio-Cortez “is some kind of unfinished project who just needs time to become more class conscious,” when in fact she has already shown herself to be a polished speaker and politician. She has already positioned herself as a loyal part of the party’s left wing, praising John McCain for being a great American, throwing her support behind Cuomo and “all” Democrats in the midterms, and voting for Pelosi as House Speaker. In a recent impressive speech, she did denounce Trump’s border policies, demanding that ICE not be funded until it behaves according to traditional liberal American values of inclusion. At the same time, she did not criticize her own party, whose alternative to Trumps physical wall is a better, more secure, “smart” wall. No doubt, she will often vote the right way on different policy proposals, and will continue to deliver good speeches and tweets; but this should not blind us to the fact that, in joining and working inside the Democratic Party, she is more “theirs” than she is “ours.” And yet, Ocasio-Cortez is being made to seem as if she is something akin to a Bolshevik deputy in the Tsarist Duma.

As a long-standing member, Todd C. knows well that the reason the ISO has not supported Sanders is not based on our criticisms of his support for building a fighter jet in his home state, or because his radicalism doesn’t reach very far beyond support for a stronger welfare system, but because he is running as a Democrat and is helping to increase the electoral fortunes of that party. It is therefore indicative of a political shift that he can write in an October 18 FB post that, “I campaigned for Ralph Nader twice, and he was far more objectionable than AOC in all sorts of ways.” That may be true, but our position on Democrats is not conditioned by their political positions, but on the party they represent.

This unprecedented shift in orientation could lead logically toward supporting Bernie Sanders in 2020? Taken in context, the refrain that “I am still not convinced of the ballot line” could become a kind of prelude (at a future special convention) to a decisive shift toward Bernie Sanders, after the organization has been sufficiently softened by talk of our “comrades” in Congress with whom we can develop close organizational and political collaboration, and so on.

This is not an argument against any collaboration with liberal, progressive, and left democrats around specific movement demands and issues. And we should defend candidates like Bernie Sanders, Ocasio-Cortez, and others, against attacks on them by both Republicans and mainstream Democrats—as we also defended Obama against racists and Hilary Clinton against sexist attacks.

We have worked with Democrats around certain campaigns in the past—for example, with Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow-Push coalition in the Campaign to End the Death Penalty. Of course, in this sense we can occasionally make common cause with politicians for the purposes of specific campaigns and demands in order to project and promote them more widely. But we never once considered Jackson a reliable, consistent ally; and we always understood, and criticized his role politically as a supporter and promoter of the Democratic Party as a home for progressives and the Left.

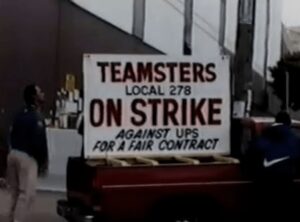

James Cannon explanation of the Trotskyists attitude toward Minnesota Farmer-Labor Governor Floyd Olson during the 1934 Minneapolis Teamsters’ strike is instructive:

The strike presented Floyd Olson, Farmer-Labor governor, with a hard nut to crack. We understood the contradictions he was in. He was, on the one hand, supposedly a representative of the workers; on the other hand, he was governor of a bourgeois state, afraid of public opinion and afraid of the employers. He was caught in a squeeze between his obligation to do something, or appear to do something, for the workers and his fear of letting the strike get out of bounds. Our policy was to exploit these contradictions, to demand things of him because he was labor’s governor, to take everything we could get and holler every day for more. On the other hand, we criticized and attacked him for every false move and never made the slightest concession to the theory that the strikers should rely on his advice.

Bernie Sanders, AOC, and Tlaib are self-described socialists (of a very moderate variety), but they are not even identified with a nominally independent labor party, as Olson was when he was governor of Minnesota in the 1930s. They are fully and openly committed to the Democratic Party. We should definitely demand things of them; but we should also not make the “slightest concession” to their politics (improve the party, draw in the left, close ranks around Democratic candidates to “beat the right”) or fail to attack them for “every false move.” Neither should we place ourselves in the position of taking responsibility for their politics (which are largely left-liberal, New Deal politics). Can we collaborate with them on specific campaigns or demands? That is entirely possible. But we must do so carefully, and without any illusions that they are “ours.”

Democrat like AOC (and Ron Dellums, who for years was the lone socialist in Congress as a DSA member) can well have a stellar voting record in congress by left standards, but the fact remains that they are members of a party of US capitalism and imperialism, and that they close ranks around “party unity” to get Democrats elected, and, by promoting working inside the party to change it, reinforce illusion in the party and help prevent the formation of independent alternatives. So while we can, and have, collaborated with politicians on specific campaigns—like the campaign to end the death penalty worked occasionally with Jesse Jackson operation Push—that has never led us, until now, into considering such politicians our “comrades” or our “allies” in Congress.

If the ISO decides now that we can campaign closely with these Democratic Party politicians on such an organized, ongoing basis, without jeopardizing our independence; and if, as Todd C. argues, this relationship will help them change history and allow them to resist cooptation, then it isn’t clear why it is that we did not endorse them and campaign for them when they were running for Congress in the first place.

Implications for our organizational forms

We can see from all of this the role that discussions of the ISO’s culture and organizational norms cannot be separated from these political developments. They are clearly intimately connected.

The point being made here is not that there haven’t been cases where members have stifled discussion or read too much into questions, even if inadvertently, by aggressively asserting a position—this has happened more often than all of us would like. But for every one of these cases one could also cite the problem of experienced and confident members evading debate and creating an atmosphere of gossip and distrust because of their unwillingness to openly declare their views. These legitimate issues, that should be openly discussed and sorted through in their specifics, are being hitched to another question, however: that of how open the political boundaries of the ISO should be.

The question of how we elect our leadership bodies—slates versus individual candidature, or how we conduct debates in order to elicit full participation, are important and necessary discussions. But they are being connected to, and conflated with, the question of how we politically define what political ideas are permissible, or acceptable, within the ISO.

Jen R. makes this clear in the reprint of her speech notes for a NYC district meeting, which appeared in bulletin 6:

There was not a much of a debate at NBC about the Democratic ballot line, but it was acknowledged that it is a debate. I think we need to argue that this is not “just a NYC question” and I think we need to take seriously the question some comrades are posing about whether there is space in the ISO for people who hold different positions. This relates to issues of our internal culture of debate.

This is in fact, a crucial question, though, to my knowledge, no subsequent document has raised it. On the contrary, Jen R. and others have since denied that the questions of our political culture have any connection to our debates around the Democratic Party.

The way these issues have been connected by the “majority” is to say that the ISO has insisted on too much political unanimity, and that the ISO ought to make more space for differing opinions. On one level, I agree with this. The ISO, for example, need not have a line on intersectionality, or a line on Political Marxism, or whether or not there is a tendency for the rate of profit to fall, and many other questions. These can and should be debated, researched, discussed, considered and reconsidered.

However, the ISO should retain points of unity based on Marxist theory and our historical experience of the working class struggle—self-emancipation of the working class and the oppressed; the centrality of the Black question in the US; the need for a revolutionary party for socialism to be possible; opposition to all forms of oppression; no parliamentary road to socialism; the right of oppressed nations to self-determination; principled opposition to all forms of US imperialism, and so on. Aaron Amaral writes that we should not demand “ideological unity” on questions of “perspectives, strategy and tactics.” I fully agree. We only expect “ideological homogeneity,” he writes, around “principled parameters which we all agree upon.” Here I also agree, though as I’ve noted, there are plenty of political questions that do not fall within the parameters of perspectives and strategy that we need not take an organizational position on.

However, if this argument is used to make “space” in the ISO for members to advocate positions that violate our basic principles—for example, people who now support Bernie Sanders—then what is being proposed is not a culture of free debate within the parameters of our basic principles and program, but a culture of toleration for fundamental differences. It means the ISO should be able to contain within its organizational boundaries positions that pull in diametrically opposite directions—toward independence and away from it. We are all “comrades” fighting for the same thing, then why not make room for those who support running (and backing) socialists on Democratic ballot lines; even though this is a policy that by Natalia, Jen, Alan, and others’ own admission leads toward accommodation to the Democratic Party (“The great danger of any left presence inside the Democrats is that it fails to resist the gravitational pull that seeks to contain and neutralize it,” wrote Alan M.) Clearly, if these conceptions of the ISO take hold, then it will have has ceased to be a revolutionary organization; we take a shift toward a more social-democratic, broad-based conception of socialist organization—and we do so under the protective covering that Alan, Jen and others are giving to our members who have fallen into opportunism toward the Democrats.

Conclusion. Whither the ISO?

To summarize how I see the current situation in the ISO:

Some comrades propose that we support Democratic candidates like Sanders and AOC, insisting that this proposal remains firmly within the principle of class independence, and is merely a strategic adjustment to take advantage of new opportunities and conditions. In response, some of us argue that this represents the abandonment of fundamental principles and that whatever these comrades believe to be upholding, they are in fact turning their backs on the principle of class independence, which necessarily includes a refusal to back Democratic Party candidates or work inside this capitalist party—that doing will lead, whatever the claims to the contrary, to adaptation and absorption by the party.

A whole layer in the middle, so to speak, which includes many members of our Steering Committee, direct their fire not at the comrades who support Bernie Sanders, but at those of us who are defending our basic principles, ostensibly on the grounds that by insisting on principles we are somehow closing off debate, when in fact we are simply putting forward one side of the debate. In short, while they claim to want to have the debate, they themselves barely engage in it, caution against hasty decisions, express moral outrage that anyone could be “accused” of abandoning our principles, and so on. That is, they convert the importance of rigorous debate over this crucial question into a position in favor of conciliation, toleration, and smoothing over of fundamental differences.

If this state of affairs continues to develop in the direction it has, the ISO will have ended its historical reason for being: to organize a revolutionary organization that can be a constituent element in the future building of a revolutionary party in the United States. Instead, it will be an organization that is indistinguishable from the broad left more generally, one that is incapable of providing a left pole of attraction within it.

[1] Engels, Critique of the Draft Social-Democratic Program of 1891

Paul D'Amato is the author of The Meaning of Marxism and was the editor of the International Socialist Review. He is the author of numerous articles on a wide array of topics.