Manuel Garí, a member of Anticapitalistas in the Spanish state and member of the advisory board of the socialist publication Viento Sur, reflects on the results of elections to the regional parliament in Madrid, held on May 4. The election produced a landslide victory for the right-wing People’s Party, whose leading candidate Isabel Díaz Ayuso,ran a Trump-like campaign against “socialism” and for “opening the economy” in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. As Garí argues, this election is the opening round for future elections leading to a showdown with the Spanish state government, currently occupied by an alliance of the Socialist Party and Unidas Podemos. The results in Madrid pose many critical questions for the left. This article appeared originally on May 7 in VientoSur and was translated by the ISP. It also appeared in Alencontre.org.

The results in the Madrid regional parliament elections are the “first round”in the forthcoming elections on the level of theentire Spanish state. They laid bare some basic political problems that afflict both the traditional social liberal left and the new populist left that emerged from the mobilization of the indignados of 15 M (May 15, 2011). At the same time, there are increasing problems in the conservative People’s Party (PP). The leadership of Isabel Díaz Ayuso seemingly came from nowhere to challenge the party’s Secretary General Pablo Casado who, in turn, is trying to take advantage of the victory in Madrid. Ayuso, as she is known, is a creation of political marketing that has crystallized into a “brand” that tilts the internal balance of the PP towards harder neoliberal and right-wing positions. Those may be drawbacks if she and PP aspire to govern the country as a whole. The results in Madrid—given the specific political, economic and social characteristics of the region—cannot be mechanically extrapolated to the Spanish state as a whole. But, undoubtedly, the Spanish state “government of progress” formed by the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) and Podemos (UP, Unidas Podemos) has taken a major hit.

More seriously, the electoral result is bad news indeed for the subaltern classes, and for workers—in short, for the left’s constituencies. Trump-like neo-liberalism road-tested in Madrid improved the PP’s electoral standing in a critical social context. The health and economic situation created by the pandemic has been added to the previous factors that make up a deep “state of malaise” that crosses the whole of society in the Spanish state, as it happens in many other countries.

A dramatic situation

In the Spanish case, this malaise is aggravated for a working class that suffers unemployment —according to official records, although in reality it is higher—of 3,949,640 people in March of this year, which means 15.3 percent of the active population. Among people younger than 25, that number reaches 37 percent. At the same time, the number of workers benefiting from the extraordinary measures of the Expediente de Regulación Temporal de Empleo (ERTE, unemployment insurance for temporary layoffs) reached 638,283 people by the end of April. The food lines in front of the public, private and popular soup kitchens are a painful reality. The “social shield” measures of Pedro Sánchez’s government—such as the miserable Minimum Vital Income created for extreme cases—many times don’t come through, are delayed and are insufficient. The Spanish economic structure—with a tourist services sector that accounted for almost 13 percent of GDP in 2019 before COVID-19—and the network of bars, taverns and restaurants that employ local people, has suffered harshly from the effects of the pandemic.

In these conditions, the Spanish government, with an increase in public debt approaching 130 percent of GDP, is banking on the European Union’s Next Generation Funds, loans and subsidies that will go right into the pockets of big business while ignoring the public sector. The PSOE-UP coalition government maintains a neoliberal economic policy governed by economics minister Nadia Calviño. It doesn’t try to implement fiscal reforms that would strengthen the public sector, and its approach to social problems offers weak welfare payments without tackling the root causes of poverty.In short, the popular classes do not see a solution from the left on the horizon. Meanwhile, inequalities between capital and labor, rich and poor, workers with decent jobs and workers with precarious jobs, men and women, over 35 and under, inhabitants of the big financial centers and citizens of the depressed regions, are increasing. Just as in poorer countries, with obvious differences aside, there are broad strata of the population that have found themselves faced with the dilemma of getting sick from COVID or suffering from a lack of income. This is key to understanding the popular mood and consciousness.

Another very negative factor accompanies this objective situation for the working class: demobilization and passivity in the face of the situation. The big trade union federations follow a policy of collaboration with the bosses that weakens the correlation of forces by the day. And despite a lot of talk, the unions have not forced the government to defend the value of retirement pensions, to increase the promised minimum professional wage, nor to repeal the labor legislation that has left workers without many their rights and the unions themselves without the capacity for effective collective bargaining. There are defensive and scattered struggles in companies threatened by closure and pockets of social resistance for the right to housing or public health, but we are far from the mass mobilizations of 2011 to 2015 when the “mareas” brought tens of thousands to the streets. [Note: The “mareas” (“tides” in Spanish) were mass demonstrations where participants wore similar colors, such as white for the healthcare workers, green for the teachers, etc.]

Most activists have hovered around the left regional governments, and, above all, the Spanish state coalition, and many of its components have been coopted in one way or the other into the governing apparatus and work inside institutions. The result is that an important source of movement energy in struggles over housing, the environment, women’s rights and anti-racism has declined while activists looked to legislative solutions that haven’t materialized or became broken promises, all leading to demoralization. At the same time, the cycle of mobilizations for national rights in Catalunya has entered, at least for now, a phase of retreat. The main conclusion that we can draw is that the political cycle that opened after May 15 of 2011 (the movement of the Indignados) has ended, and we find ourselves in a new phase of popular organization worse than it was before the formation of the Socialist-UP government.

Votes and first considerations

The elections of May 4 were the result of a snap election. The incoming regional parliament will have a term of two years, as it fills out the remainder of a four-year term. The PP’s Ayuso engineered the snap election to take advantage of her increased prestige following a bizarre maneuver the Socialists pulled off in another regional government (Murcia). That maneuver doesn’t deserve an explanation here, other than to say that it stemmed from Pedro Sánchez’s (the prime minister and leader of the Socialist Party) political operation under Iván Redondo, a Twenty-first century Rasputin, who has advised multiple parties.

In the event, the People’s Party (PP) obtained an excellent result, winning 65 of the 136 seats that make up the chamber, surpassing all of those the left won (58). Together with the 13 seats the far-right Vox won, the right, including the far right, will have 78 seats, 20 more than the whole left. With a record turnout for a regional election of 76.2 percent—which, theoretically, was supposed to benefit the left—the right won 57 percent of the popular vote against 42 percent for the left. An unmitigated catastrophe.

The PP had been governing the Madrid government for more than two decades, but on May 4, it won almost all towns and cities in the region (except in two small and marginal municipalities). It won all the electoral districts in the city of Madrid, including the neighborhoods and towns of the traditionally left-of-center“red belt.”

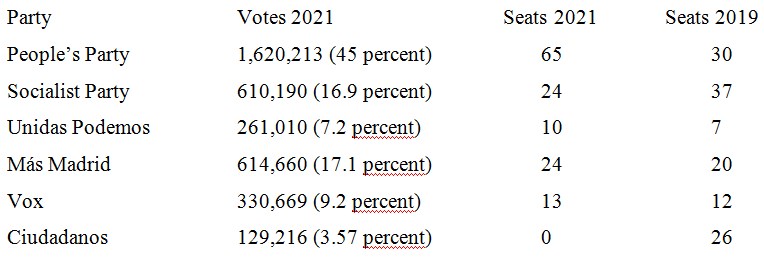

The following table with the provisional data is significant:

It’s clear that President Díaz Ayuso’s Trump-like “Texas-style”rhetoric that put business profits ahead of public health, has support among wide swathes of society. Certain business sectors benefit, but, at the same time, a narrow and selfish conception of consumerist “freedom” has advanced among the middle classes. And more seriously still, many workers with very precarious jobs and at-risk incomes faced the dilemma of choosing between two risks: health or hunger.

It was surprising that the PP began its campaign by running on “Socialism or Freedom” which later became“Communism or Ayuso”. It was surprising to hear thousands of people shouting the word “Freedom” in front of the PP headquarters on election night. It is a politically empty expression but it manifests an individualistic sentiment that identifies “freedom” with private business and leisure. As with Trump, to whom the real economic and health figures did not matter, Ayuso generated a parallel reality that permeated popular sectors. Despite having a very negative record on managing the pandemic and the economy, Ayuso achieved three goals with the help of the media and a very organized party in line with its social bases:the Catholic Church, private schools subsidized with public money, and the companies benefiting from the privatization of health care. In the first place, it substituted its “truths”for reality by means of lies. Second, it created the idea of a Madrid-style “way of life” (grotesque as it may seem) whose identity was under threat from the Spanish government. Third, and most importantly, it determined the framework in which the political debate, the campaign and the key issues unfolded, ensuring that it was not just a regional matter but Spanish in scope. True, this hides the reality of a region in which construction companies (both public works and real estate) have received important perks and injections of money from the government, but a web of interests has been created around private education and health, strongly supported to the detriment of their decaying public sector counterparts.

The PP’s victory is complemented by a strong showing for the extreme right-wing Vox led by a parasite on the public trough, Santiago Abascal, whose adult life has been spent in various legislative positions and other publicly-subsidized jobs, and Rocío Monasterio, a businesswoman with a history of fraud in the exercise of her profession. Vox is an advanced disciple of (former Trump adviser Steve) Bannon. It is made up of an explosive combination of authoritarian neoliberals, those nostalgic for Francoism, parasitic rentier classes, members of the police and military, and bully-boy gym rats.

Both Vox and the PP have expressed their intention to collaborate. With the disappearance of Ciudadanos (the Citizens party)—a neoliberal party that boasted of being centrist, but whose supporters shifted to the PP—from the Madrid parliament, the Spanish nationalist right has been reconfigured. This will affect other regions as is the case of Andalusia,where the PP and Ciudadanos co-govern. But there is no doubt that, while Vox represents a potential danger that already shapes cultural debates and policies on some issues, the real explosive and toxic danger is already posed in the here-and-now by the authoritarian (“libertarian”) neoliberalism of the Madrid PP. As in a hunting pack, there are those who bark and those who bite: Monasterio yaps and Ayuso, between silly and stupid phrases, promotes effective reactionary policies, both material and ideological.

It deserves special mention that for years the whole spectrum of the Spanish right in its different versions and from its affiliated media have focused all their revanchist hatred on the person of Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias, subjecting him to personal, family, media and judicial harassment. Harassment that, during the electoral campaign, reached the point of mafia-like death threats, which have been spreading to other members of the Spanish government. This is a campaign that can only be described as abominable and dangerous.

Reconfiguration within the left

The Socialist Party had its worst electoral results in Madrid since 1977. Without a political program, its candidate, Ángel Gabilondo, made suicidal pledges such as that he was not going to raise taxes, in a regional government whose revenues have dropped by tens of billions of Euros due to the years of PP rule, or that in the fight against the pandemic he would not have adopted preventive measures such as the closing of the hotel industry different from those adopted by Ayuso. With this, Gabilondo and his boss Pedro Sánchez were trying in a failed attempt to win over the “centrist” electorate.

Más Madrid, a split off from Podemos that defines itself as green and feminist but which was even willing to govern with a party like Ciudadanos,has four years of work at the municipal level under its belt. It managed to surpass the Socialist Party by 4,000 votes, making it the main party of the conventional left. It ran an intelligent campaign, headed by Mónica García, a doctor who continues to work in her hospital and who was almost the only voice of opposition to the PP’s public health policies in the Madrid legislature. Her clear message on concrete issues around health and public health permeated the left-wing electorate. But Más Madrid’s own political and programmatic orientation—a liberal social-democratic Green party that sees itself in the image of the German Die Grünen—also shows its limits as an alternative environmentalist and socialist left capable of changing the current political situation.

Unidas Podemos is a special case because it represents what remains of the breath of fresh air on the left that Podemos projected in 2015. Anticapitalistas contributed decisively to the creation of that Podemos and worked within it until its anti-democratic internal regime forced us to leave. The UP coalition increased its representation from seven seats in 2019 to 10 in 2021. But from a political point of view, this modest improvement is another failure. The result forced its leader, Pablo Iglesias, to resign from all his internal and institutional posts. Iglesias was the exciting new political figure who burst on the scene in 2015. But in his strength also lay his weakness. Lacking a political project with a strategic horizon, he built a party, Podemos, in which he had the first and last word. This meant that he carried out a systematic exclusion of any other political position, making it impossible to create a democratic and participatory party structure that would have a firm organic link to the working class. It put all its chips on entering the Sánchez government. But far from strengthening its position, Podemos subordinated itself to social liberal policies. And rather than challenging the bipartisan political regime created in 1978, as it proposed to do at its founding, it ended up defending the Spanish Constitution and leaving its criticismsof the monarchy for declarations and speeches.

After his failure in the government, Iglesias, fearful that his party would not surpass the 5 percent threshold for entering the parliament in Madrid, resigned as minister of the Spanish government and vice-president to Sánchez and headed the candidacy of Unidas Podemos in the regional elections. He tried to boost the fortunes of his party, which was polling poorly, and he also wanted to be able to determine the policy of the left in Madrid as a member of the regional government. During the campaign he focused his efforts on polarizing the debate with Ayuso and Vox by posing the choice as“Fascism or Democracy”. This was the old Popular Front approach that hid a Eurocommunist orientation as it searched for the old Stalinist identity from the Spanish civil war.This appeal had no relevance to the concerns of the mass of the population nor to today’s real situation for which the Europe of the 1930s had no resonance. What was even more ridiculous, UP based its anti-fascist appeal on the Constitution of 1978, which was product of the pact between Francoists and reformists. That constitution guarantees that the king, heir to one Franco appointed, is the head of state. It preserves the market economy, facilitates the educational and economic privileges of the Catholic Church, prevents the right to self-determination and sovereignty of nations with the Spanish state and confers to the army the role of guarantor of the unity of Spain.

Podemos, Izquierda Unida and the Communist Party (PCE) today form a confused post-communist amalgam under the brand of UP led absolutely by Iglesias, with no activist weight behind it and without a political program distinct from the Socialists. Iglesias’s last episode of resigning all of his positions left Podemos in a deep internal crisis that portends a ferocious power struggle. It’s a crisis that will also have consequences inside UP. But his resignation is, more than anything, an expression of the failure of a populist orientation with no program nor proposal for society, and of actions based on one-person rule in the model of an anti-democratic party. And above all, it shows the failure of the left proving its ability to govern, that old Eurocommunist obsession of entering governments or taking ministerial posts as a sine qua non condition for survival.

One last consideration. The revolutionary Marxist left also has important problems to solve. The first and not the least of them is its scarce social, political, and electoral influence. It has the obligation to reinvent itself. A political cycle has ended but the tasks ahead are more complex than they were at its onset. We must combine the patient work of reconstruction of popular organizations and social resistance, the elaboration of a new ecosocialist program, the construction of a solid anti-capitalist political pole of attraction and of new social and political alliances. We must discuss electoral experiences that will allow the revolutionary left to play an active role in the recomposition of the movement and to prevent it from falling into irrelevance.

But we can leave this question for another future article.