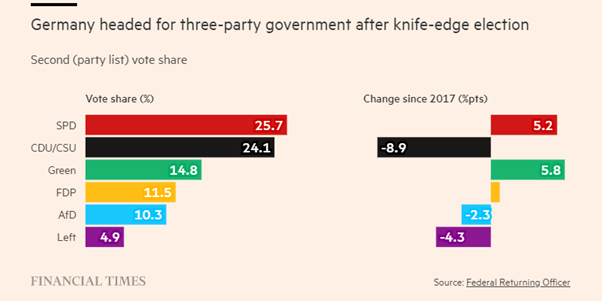

The result of German Federal election was almost exactly as the opinion polls predicted. The Social Democrats (SPD) got the largest share of those voting (25.7%), up 5.2% pts from the 2017 disaster. The Christian Democratic and Christian Social Union (CDU-CSU) vote share slumped to 24.1%, its lowest vote share since it was formed. The Greens polled 14.8%, less than previous polls forecast, but still the best result ever for them (up 5.8% pts). The small business, free market Free Democrats (FDP) took 11.5% (up slightly from 2017).

The leftist Die Linke suffered badly, dropping to just 4.9%, down from 9.2% in 2017. It seems that many leftist voters switched to the SPD in order to defeat the CDU-CSU. The anti-immigrant Alternative for Germany (AfD) also lost ground, dropping 2.3% pts, although it held its voter base in the poorer parts of eastern Germany.

The overall turnout was 76.6%, up just 0.4% from 2017. This sounds high compared with elections in the US or the UK, but actually it’s low by German standards even after the annexation of East Germany in 1990, where voting is lower.

As forecast by me, the share of the vote for the two major parties fell below 50% for the first time in the history of the Federal Republic. And given the turnout, it meant that both parties gained less than one-fifth each of the 61m eligible votes – hardly a mandate. German politics has fragmented – not good news for the German capitalists as it has become more difficult to ensure ‘continuity’ for the interests of capital.

No one party has a clear majority in the Bundestag so there will be months of wrangling. SPD leader Olaf Scholz must be favourite to form a governing coalition, but potential partners, the Greens and the FDP, do not agree on economic and social policies, and the ‘free market’ FDP would prefer a coalition with the CDU-CSU. The SPD and the Greens want to form a coalition but the FDP will have to be persuaded by offering them the finance ministry and therefore stopping any rises in taxes or regulation on business and not allowing government debt to rise further i.e a degree of ‘austerity’. The Greens want to accelerate Germany’s move towards reducing carbon emissions, but they don’t have any credible policies to achieve that within the restrictions imposed by German capitalism. Hiking minimum wages and reducing the speed limit on German motorways is about as far as it will go.

Germany is the EU’s most populous state and its economic powerhouse, accounting for over 20% of the bloc’s GDP. Germany has preserved its manufacturing capacity much better than other advanced economies have. Manufacturing still accounts for 23% of the German economy, compared to 12% in the United States and 10% in the United Kingdom. And manufacturing employs 19% of the German workforce, as opposed to 10% in the US and 9% in the UK.

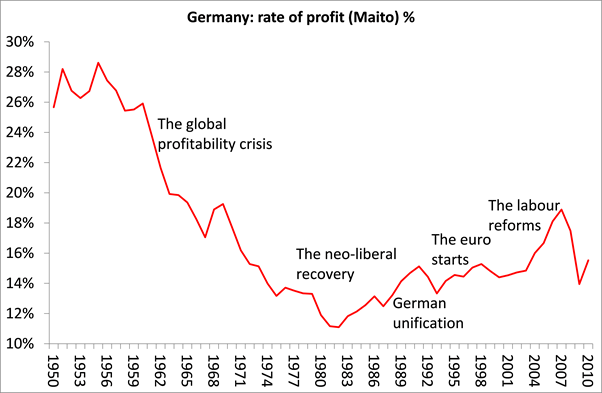

German capitalism’s relative success compared to other major European economies has been based on three factors. The first is that German industry used the expansion of the European Union to relocate its key sectors into cheaper wage areas (first, Spain and Portugal, and later in nearby Eastern Europe). This counteracted the sharp fall in the profitability of capital experienced in the 1970s (as in many other major capitalist economies).

Second, German capitalism benefited most from the setting-up of the single currency zone, placing it in strong competitive position in trade within the Eurozone and keeping capital purchases abroad cheap.

Finally, the so-called Hartz labour reforms introduced under the last SPD government created a dual wage system that kept millions of workers on low pay as part-time temporary employees for German business. This is a modern version of what Marx called a ‘reserve army of labour’. It laid the basis for the sharp rise in the profitability of German capital from the early 2000s up to the global financial crash.

About one quarter of the German workforce now receive a “low income” wage, using a common definition of one that is less than two-thirds of the median, which is a higher proportion than all 17 European countries, except Lithuania. A recent Institute for Employment Research (IAB) study found wage inequality in Germany has increased since the 1990s, particularly at the bottom end of the income spectrum. The number of temporary workers in Germany has almost trebled over the past 10 years to about 822,000, according to the Federal Employment Agency.

So the reduced share of unemployed in the German workforce was achieved at the expense of the real incomes of those in work. Fear of low benefits if you became unemployed, along with the threat of moving businesses abroad into the rest of the Eurozone or Eastern Europe, combined to force German workers to accept very low wage increases, while German capitalists reaped a big profit expansion. German real wages fell during the Eurozone era and are now below the level of 1999, while German real GDP per capita has risen nearly 30%.

However, even German capitalism, the most successful advanced capitalist economy in the world, could not escape the downward forces of the Long Depression. Since the global financial crash in 2008-9, German profitability has stagnated and then began to fall from 2017, even before the COVID slump hit in 2020. Profitability is now near the lows of the early 1980s.

The COVID slump was a disaster for the fortunes of the Merkel government. The COVID death rate may have been lower than in France, Italy or Spain, but it was way higher than in Scandinavia (excepting Sweden). And just as in the UK, right-wing politicians took advantage by investing in private COVID equipment firms to make money. The government then failed to manage the hugely damaging summer floods which affected millions. The Germany economy still has not recovered to pre-pandemic levels.

And productivity levels are lower than ten years ago.

Germany’s energy-driven manufacturing sector faces serious problems in trying to meet global warming targets. Its main export destination after the US is China; and China is slowing down, while the US is demanding that Europe reduce its trade and investment connections with China. And the European Union is no longer the milch cow for German capital. The next four years for German capitalism is going to be much more difficult than the last four.

Contrary to the general impression, Germany is not an equal society. Regional disparities are large (between west and east) and, although inequality of incomes is not large by international standards, inequality of wealth is among the worst in Europe.

The SPD has won (narrowly) because it gained the votes of many on the left. These voters will expect some changes: more and better public services; taxes on the rich; higher wages. And within the SPD, there is a rising left-wing, particularly in the youth section, that wants action. Scholz is going to find it difficult to meet the demands of his rank and file and stay in a coalition with likes of the FDP.

Courtesy Michael Roberts Blog

Michael Roberts

Michael Roberts worked in the City of London as an economist for over 40 years. He has closely observed the machinations of the global capitalism from within the dragon’s den. Since retiring, he has written several books. The Great Recession – a Marxist view (2009); The Long Depression (2016); Marx 200: a review of Marx’s economics (2018): and jointly with Guglielmo Carchedi as editors of World in Crisis (2018). He has published numerous papers in various academic economic journals and articles in leftist publications.