Chicago is hurtling to an April 4 runoff election pitting right-wing, law-and-order politician Paul Vallas against Brandon Johnson, a Cook County commissioner with a close connection to the Chicago labor movement. Whatever happens in this one-party Democratic Party city—the third largest in the country and one of its leading transportation, manufacturing, and technology hubs—will have national implications.

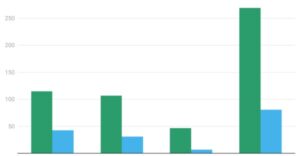

Chicago voters ousted the incumbent mayor, Lori Lightfoot, in the February 28 first-round election that set up the contest between Vallas and Johnson. Vallas placed first, with about 33 percent of the vote, to Johnson, who drew about 22 percent of the vote. Vallas, with the backing of the Fraternal Order of Police and millions from big business, hammered on the issue of “crime in the streets” to take a lead he never relinquished.

It’s tempting to call Vallas the “white backlash” or “great white hope” candidate. Some might even compare him to Bernard Epton, the sad sack Republican running on the racist slogan “Epton: Before It’s Too Late” who almost beat Harold Washington, Chicago’s first Black mayor, in 1983. While Chicago remains among the most segregated large cities in the U.S., the racial political dynamics in the city have changed since 1983. One would have to explain why Vallaswon most Asian-majority precincts by large margins, either won or came in second in most Latino-majority areas, and why mainstream Black political figures like former Illinois Secretary of State Jesse White and conservative businessman Willie Wilsonendorsed Vallas. Even J’aMal Green, who gained 2 percent of the vote in the first round—and who had posed as an activist critic of Johnson from the left—endorsed Vallas. (That’s no credit to Vallas—that’s a discredit to Green.)

What’s also interesting about the February 28 first round of voting is the contradictory messages that the results seemed to send. The mayoral race tossed out Lightfoot, the unpopular incumbent, and delivered a clear first-place finish for the conservative, pro-cop, pro-business challenger Vallas. The 50 city council races generally delivered good news to incumbents, including reelection(or near-reelection) of most of the worst political hacks on the council. In most cases where Chicago Teachers’ Union (CTU)- or Democratic Socialists of America(DSA)-backed challengers faced off against incumbents, they lost—many overwhelmingly. On the other hand, the elections to the newly created police oversight board resulted in a majority or plurality of those elected identified as police critics, from “abolitionists” to civil rights advocates.

But reading what that means is difficult, given that almost two out of three eligible Chicago voters didn’t vote. The turnout for the mayoral runoff between Vallas and Johnson isn’t expected to be much higher. That’s probably a negative for Johnson, since the voters he needs to turn out for him voted at some of the lowest rates around the city on February 28.

Although Chicago’s election is nominally non-partisan, it’s clear that the mayoral race represents a face-off between two wings of the Democratic Party: the pro-business, neoliberal, Richard Daley/Rahm Emanuel wing and the liberal wing grouped around the main city’s public sector unions and social service non-governmental organizations.

No one on the left should have the slightest idea of entertaining support for Vallas. He has long record as a neoliberal hit man from his stints as Daley-era Chicago budget director and schools CEO, to “disaster capitalism” privatizer of the schools in Philadelphia, New Orleans, Bridgeport, Conn., Chile and Haiti. He has a history of wreaking havoc on working-class families and then departing his position before the bills come due. He is a perfect example of someone who “fails upward” because he carries water for the right people.

But he is in the pole position to win the mayor’s race for two reasons. One, he is riding pro-cop “backlash politics” against Chicago’s pandemic-related spike in crime. In the first round, he won the oldest, most conservative and most affluent voters tending to live in the city’s white majority (or near majority) areas.

Two, he has corralled the lion’s share of millions from the most politically engaged business interests determined to keep a union-affiliated challenger out of the mayor’s office. Not only does he have the support of individual capitalists, he has the support of their organizations. The Chicagoland Apartment Association, Chicagoland Chamber of Commerce, Illinois Hotel & Lodging Association, Illinois Manufacturers’ Association, and the Illinois Retail Merchants Association have all endorsed Vallas.

Representing the liberal wing is Brandon Johnson, a one-time CTU-member teacher, a long-time CTU staffer, and currently Democratic Cook County Commissioner. He represents sections of the majority-Black west side of the city, the liberal white majority city Oak Park and Black majority cities of Maywood and Bellwood, among others. And in case anyone was in doubt about what his political affiliation is, Johnson recorded a straight-to-the-camera ad in which he proclaimed himself “the real Democrat for mayor”.

Johnson is running on a generally liberal platform including several fiscal and tax reforms reminiscent of that of Democratic Party liberal Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), who endorsed him. (In the 2020 election, Johnson endorsed Warren—not Bernie Sanders—in the Democratic primary for U.S. president. A few days after Warren endorsed Johnson, Sanders followed suit.)

In a race that the issue of crime and public safety has dominated, Johnson stood out as someone who at least had a platform that included elements besides policies on crime and policing. But he is hardly the police “defunder” that his critics (or supporters) make him out to be. In fact, he has spent months distancing himself from statements supporting “defunding the police” he made in the wake of the 2020 George Floyd uprising. In a March 14 debate with Vallas, he said: “I said [defund the police] was a political goal. I never said it was mine.”

Johnson positions himself as “tough, and smart” on crime. Indeed, if one simply observed the opening frames of one of his ads, showing Chicago crime statistics, one could mistake them for one of Vallas’s ads. He has said he supports“Treatment, Not Trauma,” a proposed city ordinance to reopen mental health clinics and to deploy mental health professionals, rather than police, in non-violent crisis situations. This policy, modeled on the “CAHOOTS” program that has operated for three decades in Eugene and Springfield, Ore., may be commonsensical. But it’s hardly radical. CAHOOTS is fully integrated with the police in Eugene, and it reports that its interventions take the place of only 3-8 percent of calls to the police.

He has pledged to hire 200 more detectives and to deploy the police more efficiently. “Brandon’s plan for public safety is a comprehensive, wide-ranging policy that gets smart on crime by maintaining the current CPD budget [emphasis added] while making the department more efficient and providing new investments in additional public safety initiatives outside of the police department, including new teams of non-personnel first responders for mental health crisis calls,” Johnson’s spokesperson Ronnie Reese told the Chicago Sun-Times. As a county commissioner, he voted for two straight increases in the sheriff’s department budget so that, currently, the department has its largest budget ever.

Some of his union backers might be willing to look the other way as Johnson slides right on the issues of crime and police, because they are hoping to have a pro-worker, pro-union voice in the mayor’s office. They may want to look again.

In his first debate with Vallason March 9, Johnson made clear: “I have a fiduciary responsibility to the people of the city of Chicago, and once I’m mayor of the city of Chicago, I will no longer be a member of the Chicago Teachers Union.” Later, he added, “Look, it’s not just the CTU. As a member of the Cook County Board of Commissioners there was an ally that supported me to become a Cook County commissioner. They had a job action and I stood with Cook County government. An arbiter decided county government was right. I had to deliver, you know, that news to people who were friends of mine.” He extended this same logic to the CTU in the event that CTU demanded what the city “may not be able” to provide.

To date, Johnson has run a fairly conventional campaign, collecting endorsements from Democratic politicians, liberal NGOs, and public-sector and social service unions. Perhaps his most significant political endorsement came from his first-round rival, Democratic U.S. Rep. Chuy Garcia. Garcia showed strength in the city’s Latino neighborhoods on February 28. But whether Garcia’s endorsement can deliver the votes Johnson needs to win isn’t clear. At the same time, Johnson may need as much as 80 percent of the Black vote.

Vallas has also run a conventional Chicago Democrat campaign—pulling in endorsements from mainstream Democrats (including most city council members who have issued an endorsement to date), businesspeople, conservative church leaders and building trades unions expecting a “pro-business” mayor to “keep the cranes up” along the downtown skyline. The result on April 4 will tell whether this kind of status quo politics has staying power.

With few exceptions, most of the Chicago left and activist groups have lined up behind Johnson. For the CTU and SEIU Health Care, their allied non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and their political vehicle, United Working Families (UWF), this is no surprise. This political alliance, forged in the wake of a major defeat—Mayor “1 Percent” Rahm Emanuel’s closure of 50 schools in the year following CTU’s victorious 2012 strike—has essentially become an organizing center for the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, its rhetoric about “independence” and “working class politics” aside.

Even Rampant magazine, whose motto is “revolutionary politics—Chicago style,” took a break from arguing for the goal of smashing the capitalist state to praising UWF for choosing “union militant” Johnson to run for mayor. (“UWF’s September 2022 decision to put forward one of its own, Brandon Johnson, for mayor represents a step forward toward independence from its 2015 campaign for Chuy García.” “The UWF has achieved a tremendous amount by bringing together a cross-section of the city’s organized left and working-class organizations.”) Praising UWF, while voicing some criticisms of the record of the candidate for which UWF is “all in,” is a way of backing Johnson without saying as much.

This seems to be a trend on the Chicago left, as both Rampant and Midwest Socialist have published articles taking the tried-and-true “lesser evil” approach. These articles emphasize the disaster that will befall Chicago if Vallas were elected, urge their readers to do what they can to prevent it, without saying the obvious: “Vote Johnson”. In Rampant’s case, this may be a vestige of a waning commitment to independent politics. In the case of the Democratic Socialists of America, the sponsors of Midwest Socialist, they may just be following the advice of their founder Michael Harrington, quoted in Doug Greene’s recent biography, who told presidential candidate Jesse Jackson in 1988 that “We raised the problem with Jackson that we want to support you but we don’t want to support you in a way that would harm you.” What would Vallas do with a statement from “the socialists” supporting the “radical” Johnson?

Given the enthusiasm for Johnson on the left, one would think that an activist or radical with union experience running as a Democrat for the mayoralty of a major city is a new phenomenon. Hardly. Jean Quan, a former member of the Communist Workers Party, was mayor of Oakland, Calif. While in that position, Quan deployed that city’s brutal police force against the 2011 Occupy encampments and demonstrations. Antonio Villaraigosa—the mayor of Los Angeles (and later Democratic Party kingpin as chair of the Democratic National Convention in 2012)—was a student leader of the radical Chicano organization MEChA, a well-respected organizer for the United Teachers of Los Angeles (the CTU’s sibling local, currently involved in a major strike) and president of the LA local of the American Federation of Government Employees. Coleman Young, the long-time business-friendly mayor of Detroit from the 1970s to the 1990s, was an activist in the United Auto Workers, and a member of the Young Communist League who defied the House Un-American Activities Committee in the McCarthyite witch hunts of the 1950s.

Chicago itself is no stranger to the phenomenon of radicals and activists transforming themselves into mainstream Democratic Party politicians. The Harold Washington campaign was the entry point into mainstream politics for a generation of 1960s/1970s radicals—people like former U.S. Reps. Bobby Rush, Luis Gutiérrez and Ald. Helen Shiller. By the time each of them had retired, they had become cogs in the Daley/Emanuel machine, however much they want to rewrite that history today. Rush punctuated that with his endorsement of Vallas.

Radicals and socialists who know this history should be skeptical of claims that Johnson would somehow chart a different course if he was elected into a position that is instantly wired into the networks of finance, business development and political influence reaching to the White House. Frank L. provides a dose of reality to those who might entertain the illusion that Johnson as mayor could play “organizer in chief” for a broader working-class mobilization:

With no concrete plan for beating the capitalist class that rules our city the option available to progressives that win will be limited to managing the affairs of the city within confines already determined by the capital. Progressives would have to be content with minor adjustments to police budgets, with courting “equitable” gentrification dollars, and scoring symbolic victories. In that scenario the progressive left risks fracturing further, as some loyalists strive to paint any minor reform as far greater a victory than it really is, while the rest of the working class becomes disillusioned with an administration that continues to, willingly or not, be forced to court international investment, to rely on privatization to provide social services, and fails to tax the rich and deliver the city that we desperately need and deserve.

Could Johnson win? Sure. Polls reported as of this writing on March 23 suggest a toss-up. Nevertheless, the record of both the CTU and the UWF in the last two mayoral elections—when their favored candidates lost decisively—isn’t encouraging.

The grubby deal-making and political backsliding on display today feels far removed from the time in 2012 when CTU’s industrial action electrified the city, injected working-class and racial justice issues into everyday discussion and dealt a blow to the city’s establishment.

Lance Selfa

Lance Selfa is the author of The Democrats: A Critical History (Haymarket, 2012) and editor of U.S. Politics in an Age of Uncertainty: Essays on a New Reality (Haymarket, 2017).