A pandemic is an epidemic stretching across multiple continents. It is therefore a worldwide public health crisis. For this reason, the only effective way to combat the Covid-19 pandemic is through global coordination aimed at advancing a collective international strategy. Yet, the capitalist world order has done precisely the opposite, slamming shut national borders while nations compete with each other to buy vital supplies and develop potential treatments within the private sector.

So many countries have closed their borders to refugees that the UNHCR and other refugee resettlement agencies halted their relocation operations last month. Nationalism on the part of political leaders has reached ludicrous proportions. President Donald Trump has repeatedly and inaccurately referred to the coronavirus as “the Chinese virus” while threatening to withhold funding for the World Health Organization (WHO), alleging that the agency has been “very China centric.”

Meanwhile, Berlin’s secretary for the interior, Andreas Geisel, also ratcheted up nationalist hysteria after 200,000 face masks ordered by the German city went missing. Claiming that the masks were ordered from a U.S. company but were “confiscated” in Bangkok before arriving in Germany, Geisel accused the U.S. government of “piracy.” Days later, the Berlin official was forced to admit that he had been mistaken, and the masks had actually been ordered from a German company.

Trump has recently banned U.S.-based companies from exporting personal protective equipment (PPE) to other nations, allegedly in order to “prohibit export of scarce health and medical supplies by unscrupulous actors and profiteers.” But the president himself set the wheels in motion for this debacle, by refusing to direct federal agencies to plan production of life-saving medical gear or even testing kits—instead relying on corporations seeking maximum profits. In so doing, Trump empowered corporations to sell to the highest bidder, thereby driving up prices exponentially. This bidding war forced different nations, U.S. states, cities, hospitals and federal agencies to compete with each other to buy desperately needed supplies.

As ProPublica reported, when healthcare workers at New York City hospitals were facing nightmarish conditions, forced to their risk lives by reusing PPE because of the widespread shortages,

New York state has paid 20 cents for gloves that normally cost less than a nickel and as much as $7.50 each for masks, about 15 times the usual price. It’s paid up to $2,795 for infusion pumps, more than twice the regular rate. And $248,841 for a portable X-ray machine that typically sells for $30,000 to $80,000.

This payment data, provided by state officials, shows just how much the shortage of key medical equipment is driving up prices. Forced to venture outside their usual vendors and contracts, states and cities are paying exorbitant sums on a spot market ruled by supply and demand…

The bidding wars are also raising concerns that facilities with shallow pockets, like rural health clinics, won’t be able to obtain vital supplies.

While this pandemic is in many respects a natural disaster there is nothing “natural” about the massive death toll. Relying on the laws of supply and demand—and the quest for profits that characterizes the capitalist system—has turned an already perilous situation into a full-blown global catastrophe.

Rich nations and poor nations

The advice offered by medical experts consists of just three basic guidelines: wash hands frequently with soap and water; stay at home, going outside only for buying necessities such as groceries or exercising; practice “social distancing,” staying at least six feet away from those not in your household. Yet these straightforward tactics are impossible to implement around the world because of the grotesque inequalities produced by capitalism and its international correlate, imperialism.

People cannot wash their hands frequently if they do not have access to clean water and soap. A report by the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF, based on 2017 figures, showed that 3 billion people lack basic handwashing facilities with soap and water in their homes, while among countries with the poorest populations almost three quarters of people do not have access to basic handwashing facilities.

It is also impossible for people to shelter at home if they do not have a home or even adequate shelter. According to YaleGlobal, which based its estimates on national reports that might well underestimate the numbers, at least 150 million people, or about 2 percent of the world’s population, are homeless, while roughly 1.6 billion, more than 20 percent of the world’s population, do not have adequate shelter.

Likewise, social distancing is out of the question in already dangerously overcrowded conditions. While the early outbreaks of coronavirus took place in wealthier countries, the virus soon spread to poorer countries with impoverished and congested urban populations, including India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Nigeria and Brazil.

Meanwhile, refugees, prisoners, migrant families held in detention, among others forced into enclosed quarters, are among those most vulnerable to coronavirus. Refugee camps, for example, not only force thousands of residents into extremely close contact but also often lack clean water and soap.

In Israeli-occupied Gaza—the most densely-populated place on earth, with 2 million Palestinians packed into 139 square miles—electricity often is available for less than half of each day and there are fewer than 100 ventilators available for the population. A local doctor acknowledged, “We don’t have enough hospitals, or ICU beds, or mechanical ventilators.” She added, “If we have a positive case in the community, it will be a disaster.”

Inequality to the fore

While the pandemic has shone a spotlight on the starkly unequal access to basic necessities and healthcare between rich and poor nations, it has also exposed the obscene levels of inequality within all nations, including the richest. There is no better example than the United States, which has long held the distinction of being not only the wealthiest society in the world, but also one of the most unequal. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), in a 2017 report on the gap between rich and poor within its 36 member states, ranked the U.S. the third most unequal, behind only Mexico and Chile.

Native Americans living on reservations inside the U.S., after suffering centuries of genocide and racial discrimination at the hands of European colonizers, face deprivation similar to poor populations worldwide. For example, almost 40 percent of those living in the Navajo Nation reservation—with a population of 175,000 and just four hospitals—live in homes without running water or sanitation, while one in ten homes do not have electricity. Despite widespread poverty, residents of Navajo Nation must pay about 13 cents for a gallon-jug of water–roughly 72 times more than the rate paid in the neighboring suburbs of Arizona or New Mexico.

In comparison to European and other wealthy societies that long ago adopted social democratic reforms—even if they have been severely eroded in the era of neoliberalism—the U.S. government has never extended to its working class even the most rudimentary social safety net. The notions of government-sponsored paid parental or family medical leave, subsidized childcare and universal access to even the most minimal level of healthcare are unheard of in the U.S. Most importantly in this pandemic, health coverage has long been dependent on whether individual employers choose to offer it as a “benefit” to its workers—a benefit which has been dramatically declining in recent decades.

In other words, healthcare has never been a right in the U.S., which is exacerbating the class consequences of this pandemic. The lower the wages earned by workers, the less likely they are to be given paid sick days or medical insurance. Those who have suddenly lost their jobs working at restaurants, bars, gyms, hair salons and a multitude of other service occupations have been left without any income at all over recent weeks.

In addition, the so-called “self-employed,” including gig workers earning poverty wages such as Uber drivers and Amazon Prime and Instacart “shoppers” who deliver groceries and other goods to those who can afford it, find themselves in an equally terrifying position. Their common plight is summarized succinctly in the following phrase: “If I don’t work, I don’t get paid.” Which means if they don’t work, they can’t eat, can’t pay their rent, can’t afford healthcare and a host of other necessities.

Although the stimulus package that was passed through Congress on March 25th and then signed by President Trump guaranteed that low-wage and gig workers were included in the rescue, CNBC reported on April 4,“A notice on the front page of Michigan’s Department of Labor and Economic Opportunity website reads: “Self-Employed Workers, Gig Workers, 1099-Independent Contractors and Low-Wage workers — DO NOT APPLY AT THIS TIME. Applications will be open in the next few days.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has therefore become a full-blown social crisis for the U.S. working class. Nearly 17 million people filed for unemployment benefits in the three weeks ending on April 9th. That figure does not include the many more who tried to file but were unable to because so many states’ unemployment websites and phones have been overwhelmed by the numbers trying to register. How many people who have lost their jobs over the last three weeks are entirely without income? No one yet knows. But the IRS announced in early April that the paltry stimulus checks of between $600 and $1,200 for individuals will take up to five months to deliver.

On March 24th, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis estimated that layoffs in the second quarter of 2020 (between April and June) will be 47.05 million, and unemployed persons will be 52.81 million—amounting to an unemployment rate of 32.1 percent. It added, “These are very large numbers by historical standards, but this is a rather unique shock that is unlike any other experienced by the U.S. economy in the last 100 years.”

At the height of the Great Depression in 1933, unemployment peaked at 25 percent. Some economists have predicted that this recession will be sharp but short. Others are anticipating a longer contraction, much like the Great Depression. Once again, no one knows. Already, the large number of people lining up to get groceries from food pantries resembles those of the 1930s.

The only thing that is known is that the capitalist system is entirely incapable of (and uninterested in) rescuing the working class from destitution.

The role of racism

Class distinctions in the U.S. have always included a strong racial component, and Black people and other people of color have never had equal access to education, decent paying jobs, healthcare and housing. A case in point: Black mothers in the U.S. die at three to four times the rate of white mothers during and immediately after childbirth, a figure that has risen in the last decade. This disparity is not a function only of poverty, but also of racism. One 2016 New York City study, for example, showed that middle-class Black women with college degrees had higher rates of maternal mortality than white women who did not graduate from high school.

During the current coronavirus pandemic, data that has begun emerging from individual states and cities shows striking racial disparities, although the federal government hasn’t yet begun any systematic attempt to gather this information.

Louisiana’s Department of Health reported that, although Black people make up just 32 percent of the population, they account for 70 percent of coronavirus deaths there. In Michigan, where Blacks make up just 15 percent of the population, they account for one third of cases and 40 percent of deaths. The figures are also staggering in major urban areas like Milwaukee and Chicago. In Milwaukee County, where Black people make up just 26 percent of residents, Blacks accounted for more than 80 percent of the reported deaths. In Chicago, with a Black population of 30 percent, Black people accounted for 52 percent of the confirmed cases and 68 percent of the city’s deaths.

Black and Latino workers are far more likely to be categorized as essential workers who cannot afford to miss a day’s pay by staying at home. Fewer than one in five Latinos can work from home, and Latino workers are much more likely to be uninsured and without any access to affordable healthcare.

Many people of color who have died from respiratory failure in recent weeks have not been counted as Covid-19 deaths because they were not tested before they died, so the official figures certainly underestimate the proportion of Black and Brown people dying.

Even following the protective measures advised by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to wear masks in public threatens the safety of Black and Brown people simply because of racism. Two Black men wearing protective face masks were thrown out of an overwhelmingly white Illinois suburban Walmart by a white police officer in March, who held his hand to his gun as he escorted them out. The video, which went viral, leaves no room for doubt about the sequence of events.

The intersection of race and class has shown itself in other ways during the pandemic. The Los Angeles school system, for example, recently reported that since it adopted online education on March 16th, roughly 15,000 high school students have been entirely absent online and have not submitted any schoolwork, and more than 40,000 have not been in daily contact with their teachers–amounting to fully one third of all high school students in the school district. The district is just 10.5 percent white, and the poorest students suffer from housing insecurity, lack of internet access and abject poverty.

The blame game

There is another aspect of racism that has been exacerbated by this pandemic: xenophobia against Asians. Trump, clearly delighted by all the attention provided by his daily press conferences, is given a speech written for him but often goes off script as he gets carried away with himself, leading him to spread misinformation—grossly exaggerating the number of COVID-19 tests available while also touting, without evidence, the anti-malaria drug chloroquine phosphate as an effective treatment for coronavirus.

He has used the press conferences to pat himself on the back for the “wonderful” job he has been doing, while blaming China for causing the virus has been a recurrent theme. (It turns out that the virus was brought to New York, the current U.S. epicenter, from Italy, not China.) Dr. Anthony Fauci, a key member of the administration’s coronavirus task force, frequently attempts to correct this misinformation, to no avail.

Other Republican politicians have repeated and even embellished Trumps’ sentiments. Texas Sen. John Cornyn blamed China for the coronavirus because of what he claimed to be a “culture where people eat bats and snakes and dogs and things like that.”

The number of hate crimes against Asians and Asian-Americans rose suddenly after Trump began calling COVID-19 “the Chinese virus.” Two-thirds of the attacks have been experienced by Asians not of Chinese descent. “Folks have been spat on, folks have gotten on public transit and the car immediately clears—everyone either goes to the other side or just leaves,” one woman told WBEZ in Chicago. “I’ve heard people be yelled at to ‘go back home’ or asked if they eat bats.” A 60-year-old Chinese-American man was jogging in a Chicago suburb when two women attacked him: one of the women threw a log at him, accused him of being sick, told him to ‘go back to China,’ and spat at him.”

President Donald Trump’s infamous response to reporters’ questions about the long-standing shortage of Covid-19 tests was “No, I don’t take responsibility at all.” This has been his persistent refrain as he went from denial (“One day — it’s like a miracle — it will disappear,” he claimed on February 27th) to blaming individual governors and hospitals for the lack of testing and PPE (On March 19th, Trump directed governors begging for PPE from the national stockpile to “get [supplies] yourself,” adding, “The Federal government is not supposed to be out there buying vast amounts of items and then shipping. You know, we’re not a shipping clerk”.)

To date, Trump’s main preoccupation seems to be restarting the economy on behalf of his corporate cronies. At his press conferences, he is periodically flanked by business leaders from companies such as Procter and Gamble, Target and United Technologies who he praises for the great job they have been doing “fulfilling their patriotic duty” when their only motivation is maximizing their profits.

To date, Trump has refused to implement a national policy of social distancing, saying, “I leave it up to the governors. The governors know what they’re doing,” Trump said. “They’ve been doing a great job.” Five states still have no stay-at-home orders: North and South Dakota, Arkansas, Iowa and Nebraska. This lack of a national stay at home policy has been likened to setting up a peeing section in a swimming pool.

What did Congress know and when did they know it?

There is plenty of blame to go around. While Trump is undoubtedly guilty of criminal negligence costing thousands of lives, leading members of Congress are not far behind. In the weeks following a January 24th Senate briefing on COVID-19, four senators— Republican senators Richard M. Burr, James M. Inhofe and Kelly Loeffler, along with Democratic senator Dianne Feinstein—sold large amounts of stocks before the stock market began its downward spiral on March 9. As the New York Times reported, Burr’s stock offload is particularly suspicious because it included most of his investments, including in two hotel chains whose stock values tanked when travel restrictions were put in place. This appears to be the only congressional “action” regarding COVID-19 that took place at that time.

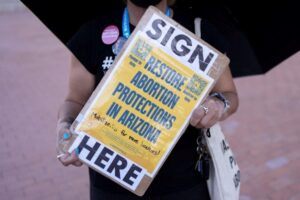

The Democratic Party establishment also did nothing to prepare the public for the emerging COVID-19 crisis. Instead, Democrats spent the period from mid-January until February 5th on its doomed impeachment hearings and trial, knowing that the Republican-dominated Senate would never find Trump guilty. After that, Democrats and their media minions dedicated themselves to a smear campaign to discredit presidential candidate Senator Bernie Sanders as a radical extremist who was “unelectable” due to his democratic socialist policies, including “Medicare for All”—likening Sanders as the left-wing equivalent of Donald Trump. Sanders went from first place in the early primaries to a far second place finish on Super Tuesday on March 3rd. Senator Joe Biden, whose campaign had been dead in the water only weeks earlier, surged into first place largely thanks to this fear mongering.

Mission accomplished! Sanders formally ended his campaign on April 7, leaving Biden, whose purported “electability” is based only on his defense of the political status quo, as the last candidate standing. But like Hillary Clinton, Biden suffers from an “enthusiasm deficit” that might keep many Democrats home on Election Day in November. One can’t help but wonder whether the experience of the COVID-19 healthcare calamity, not to mention Depression-level unemployment, will cause many more working-class people to embrace Medicare for All and democratic socialism in the coming months.

“Essential” yet expendable: frontline workers in the age of coronavirus

The ruling class has long employed a “divide and conquer” strategy, intended to pit ordinary people against each other, and this has been amplified during this pandemic, as outlined above. Yet many ordinary people, themselves suffering the trauma of sudden poverty, lack of healthcare coverage and uncertainty at every level, have performed tremendous acts of kindness and generosity to their neighbors and even strangers in these horrendous times—from delivering groceries to and checking in on those most vulnerable to make sure they are surviving.

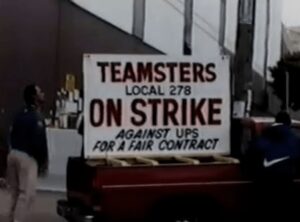

In February, the U.S. had been at nearly full employment, with a 3.5 percent unemployment rate, and wages had finally started to rise 12 years after the 2008 Great Recession began. National strike statistics had not yet risen significantly, but K-12 teachers over the previous two years had taken important strike actions, beginning in West Virginia and other “red states” followed by large urban teachers’ unions in “blue states,” including teachers in Los Angeles and Chicago.

While on the defensive, there are some encouraging signs that those workers on the frontlines, forced to risk their lives because they have been categorized as “essential” are learning creative ways to fight back in this new age of social distancing—from labor protests to safety strikes, demands for “hazard pay” and paid sick leave. So far, these have been small-scale, local actions that nevertheless point the way forward toward working-class solidarity as the social crisis deepens.

Those workers considered “essential” and therefore forced to work at this time have neither been fairly compensated nor provided with adequate PPE by either the federal government or their private sector employers, who are currently raking in massive profits in the marketplace. Frontline workers, from healthcare and warehouse workers to delivery drivers and food processing workers, regularly working mandatory double shifts, have often been denied basic protections—including masks, gloves and hand sanitizer— while forced to remain in close contact with other workers by their employers, who have continually downplayed or hidden deaths among their employees.

These workers have been deemed “essential”, yet the government and their employers treat their lives as expendable. For this reason, some of these workers have started taking action.

Nurses, doctors and other healthcare workers have held protests, standing six feet apart, around the country. At Mount Sinai Hospital and Harlem Hospital in Manhattan, healthcare workers held signs with pictures of their dead coworkers.

One group of Chicago Amazon workers staged a “safety strike” involving car caravans blocking the exits in early April, with truck drivers supporting the strike after they were told that two workers at the site had already tested positive for COVID-19—a fact that Amazon management had hidden from them. The workers demanded that Amazon shut down the facility for two weeks for disinfecting, providing the workers with full pay. While Chicago police (unsurprisingly) shut down the picket on behalf of Amazon, the strikers vowed to continue fighting.

A leader of another strike action at an Amazon warehouse in Staten Island, New York, provided an eloquent defense of his motives when he was fired by the company after he helped organize a walkout on March 30. As reported by the Guardian newspaper, Chris Smalls, a manager assistant who supervised 60-100 low wage “pickers” who take items from the shelves and place them on conveyor belts, wrote an open letter to Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon and the richest person in the world, with a net worth of $115 billion.

After learning of the first confirmed case of COVI-19 at the warehouse (which upper management demanded be kept secret from other workers), Smalls instead spread the information to other workers. He wrote,

[My co-workers and I] went to the general manager’s office to demand that the building be closed down so it could be sanitized. We also said we wanted to be paid during the duration of that time. Another demand of ours was that people who can’t go to work because of underlying health conditions be paid. Why do they have to risk catching the virus to put food on the table? This company makes trillions of dollars. Still, our demands and concerns are falling on deaf ears. It’s crazy. They don’t care if we fall sick. Amazon thinks we are expendable…

Because Amazon was so unresponsive, I and other employees who felt the same way decided to stage a walkout and alert the media to what’s going on. On Tuesday, about 50-60 workers joined us in our walkout. A number of them spoke to the press. It was beautiful, but unfortunately I believe it cost me my job.

Smalls concluded, “And to Mr. Bezos, my message is simple. I don’t give a damn about your power. You think you’re powerful? We’re the ones that have the power. Without us working, what are you going to do? You’ll have no money. We have the power. We make money for you. Never forget that.”

Attached picture courtesy The Paris Photographer

Sharon Smith is the author of Subterranean Fire: A History of Working-Class Radicalism in the United States (Haymarket, 2006) and Women and Socialism: Class, Race, and Capital (revised and updated, Haymarket, 2015).