Is inflation coming back in the major capitalist economies? As the US economy (in particular) and other major economies begin to rebound from the COVID slump of 2020, the talk among mainstream economists is whether inflation in the prices for goods and services in those economies is going to accelerate to the point where central banks have to tighten monetary policy (ie stop injecting credit into the banking system and raise interest rates). And if that were to happen, would it cause a collapse in the stock and bond markets and bankruptcies for many weaker companies as the cost of servicing corporate debt rises?

The current mainstream theory for explaining and measuring inflation is ‘inflation expectations’. Here is how one mainstream economic paper put it in relation to the US: “Over the longer-term, a key determinant of lasting price pressures is inflation expectations. When businesses, for example, expect long-run prices to stay around the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent inflation target, they may be less likely to adjust prices and wages due to the types of temporary factors discussed earlier. If, however, inflationary expectations become untethered from that target, prices may rise in a more lasting manner.”

But expectations must be based on something. People are not stupid; businesses and households’ expectations of whether prices are going rise (faster) depend on some guesses or estimates of how prices are moving and why. Moreover, expectations of price rises do not explain the price rises themselves.

There is a reason why mainstream economics has been driven into this ‘subjective’ corner in explaining and forecasting inflation. It’s because previous mainstream theories of inflation have been proven wrong. The main theory of the post-war period was the monetarist one, which I have discussed before. Its basic hypothesis is that price inflation in the ‘real’ economy occurs and accelerates if the money supply rises much faster than production in an economy. Inflation is essentially a monetary phenomenon (Milton Friedman) and is caused by central banks and monetary authorities interfering in the harmonious expansion of the capitalist economy.

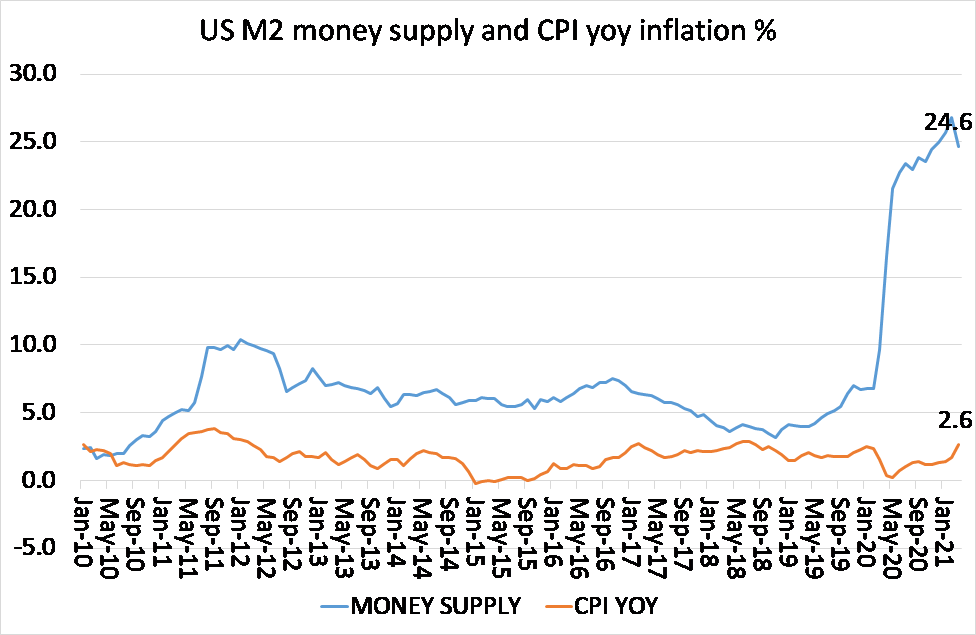

But the monetarist theory has been proven wrong, particularly during the COVID slump. During 2020, money supply entering the banking system rose over 25% and yet consumer price inflation hardly budged and even slowed.

Monetarist theory has been proven wrong because it starts from the wrong hypothesis: that money supply drives prices of goods and services. But the opposite is the case: it is changes in prices and output that drives money supply.

Take the monetarist formula: MV=PT, where M is the money supply; V is the velocity of money (the rate of turnover of money exchanges); P = prices of goods and services and T = transactions or actual real production activity.

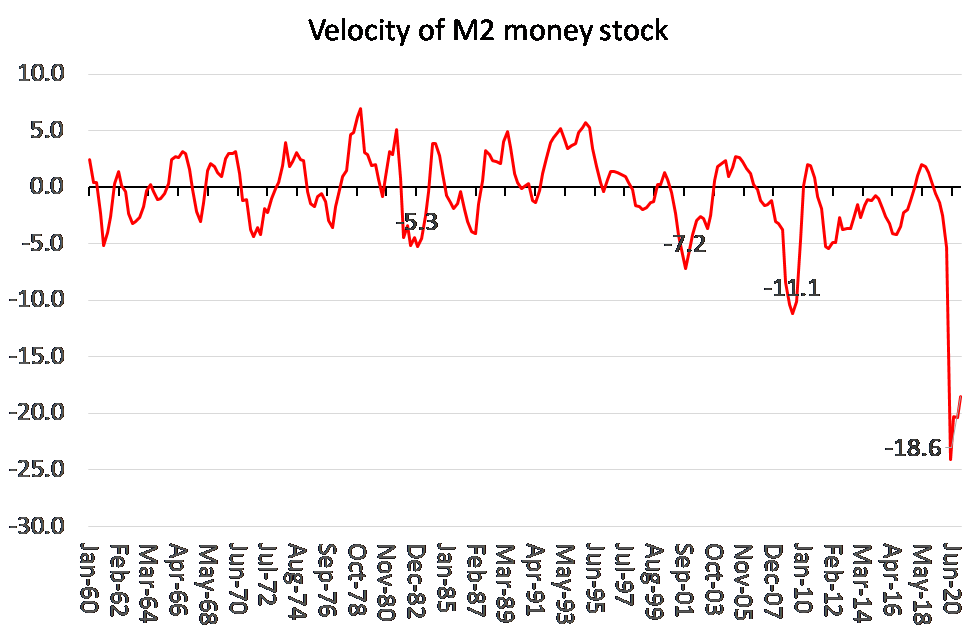

Monetarist theory assumes that the velocity of money (V) is constant but this is just not true, especially during slumps and the COVID slump in particular.

The huge rise in money supply (M) has been dissipated by the unprecedented fall in the velocity of money (V). So MV, the left-hand side of the monetarist equation, has not moved up much at all. Contrary to monetarist theory, prices of goods and services have not been driven by the money credit injections.

But has this money disappeared then? No, it’s still there, but the money injections by the Federal Reserve and other central banks, mainly achieved by ‘printing money’ and purchasing huge quantities of government and corporate bonds, as well as making loans and grants, have ended up, on the whole, not in the hands of businesses and households to spend, but in the deposits of banks and other financial institutions. This money has been hoarded or used to fund speculation in financial assets (a booming stock market and investment in hedge funds etc). So the velocity of money (V) in goods and services transactions has plummeted.

The alternative mainstream theory of inflation is the Keynesian one. This is fundamentally a ‘cost-push’ theory, namely that companies push up their prices when their costs of production rise, particularly wages, the largest part of costs of production. In effect, Keynesian theory is a wage-push theory. Inflation depends on the relative demand for and supply of labour forcing up wages. So the argument goes: the lower the unemployment rate and the higher the demand for labour relative to the available supply, the more wages and then prices will be forced up. Keynesian theory sees inflation as being caused by workers getting too high wage increases (and eventually losing out in real terms as price rises eat into wage increases).

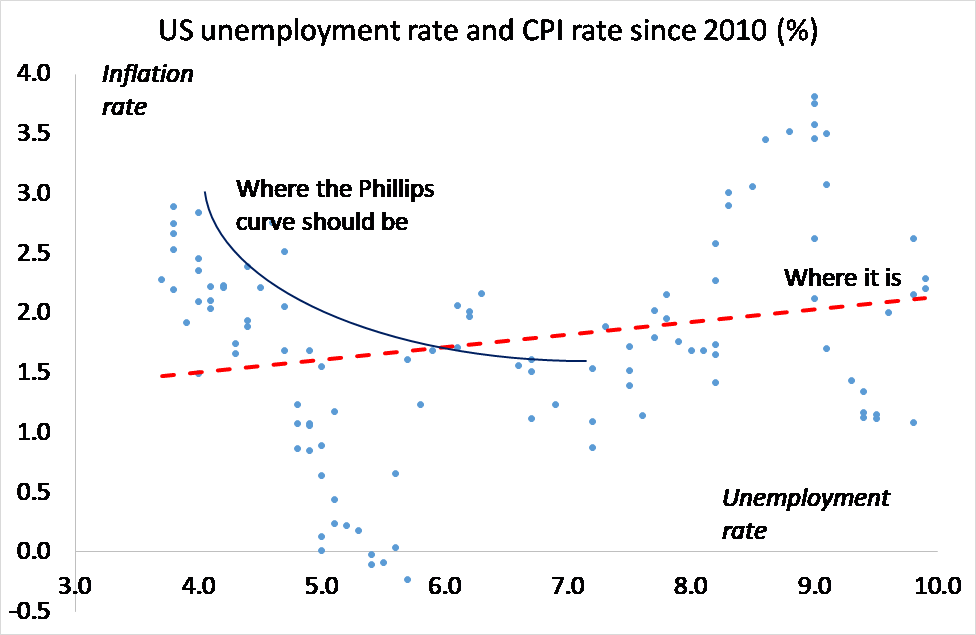

The usual Keynesian way to estimate likely changes in inflation is to use the so-called Phillips curve: the curve of the statistical relation between unemployment rate and the price inflation rate. Again, however, this theory has proven to be false. The ‘curve’ does not hold or is so ‘flat’ as to provide no guide to inflation. Indeed, since the Great Recession of 2008-9, unemployment rates in the major economies have dropped to near all-time lows and yet wage rises have been relatively moderate and inflation rates have slowed. This is the mirror image of the 1970s when unemployment rates rose to highs but so did inflation and we had what was called ‘stagflation’. Both examples show that the Keynesian cost push theory is false. In the Figure below, based on monthly data, the blue line shows where the Keynesian Phillips curve should be if it works; and the red line shows where it actually is. Indeed, the red line shows that falling unemployment leads to slowing inflation, at least since 2010!

The problem with Keynesian inflation theory is that it assumes that profits comes from investment and not from the exploitation of labour power. Keynesian theory says that S (surplus value) is the result of C (capital stock) and not V (labour power). So if C is steady, then S is steady and any price rises must come from V (wages rises). Marx’s view was different. In his speech to trade unionists in 1865, he argued against the view that wage rises cause inflation. In his view, a rise in V will generally lead to a fall in S (profits), not a price rise. That is why capitalists oppose wage rises vehemently.

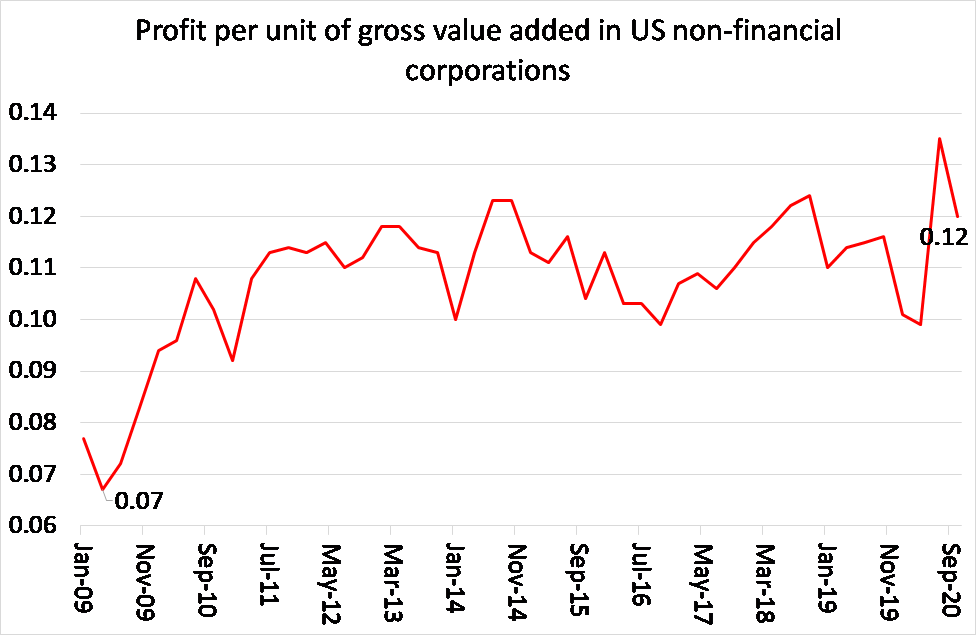

And there is no wage push inflation. Indeed, over the last 20 years until the year of the COVID, real weekly wages rose just 0.4% a year on average, less even that the average annual real GDP growth of around 2%+. It’s the share of GDP growth going to profits that rose (as Marx argued in 1865).

If there is going to be any ‘cost-push’ this year, it’s going to come from companies hiking prices as the cost of raw materials, commodities and other inputs rise, partly due to ‘supply-chain’ disruption from COVID. The FT reports that “price rises have emerged as a dominant theme in the quarterly earnings season which kicked off in the US this month. Executives at Coca-Cola, Chipotle and appliance maker Whirlpool, as well as household brand behemoths Procter & Gamble and Kimberly-Clark, all told analysts in earnings calls last week that they were preparing to raise prices to offset rising input costs, particularly of commodities.”

To really get a grip on what causes inflation and whether it is coming back after COVID, we must return to Marx’s value theory. The demand for goods and services in a capitalist economy depends on the new value created by labour and appropriated by capital. Capital appropriates surplus value from exploiting labour power and buys capital goods with that surplus value. Labour gets wages and buys necessities with those wages. Thus it is wages PLUS profits that determines demand (investment and consumption).

Going back to the monetarist formula MV=PT. If MV is unchanged as it broadly was in the COVID slump, then any change in P (prices) will depend on any change in T (the new value of goods and services produced).

Over the longer term, growth in T tends to slow. Why? Because T is based on capitalist production for profit and as capitalists tend to try and raise profits through mechanisation and the replacement of labour, there is a relative decline in new value produced (because only labour can create value, not machines). If the growth of T slows, then there is a tendency for price inflation to slow. And that is proven empirically. As the rate of profit began to fall in most major economies after the late 1990s and growth in new value dropped, particularly in the last decade, so price rises have ebbed.

Now workers don’t want inflation as it eats into real living standards. But capital does like some inflation, as price rises enable companies to expand production and increase profits at the expense of wages. Thus central banks and monetary authorities try to combat the long-term tendency for price inflation to ebb by injecting money and credit (more M). Money supply acts as a countertendency to slowing value creation. Thus the rate of inflation (P) depends on both M and T. Of course, in practice the Fed and other central banks cannot ‘manage’ inflation as it depends on what is happening in capitalist production. Indeed, for the last 20 years, central banks have failed to achieve their target rate of inflation of around 2% a year with monetary zig zags on interest rates and monetary controls.

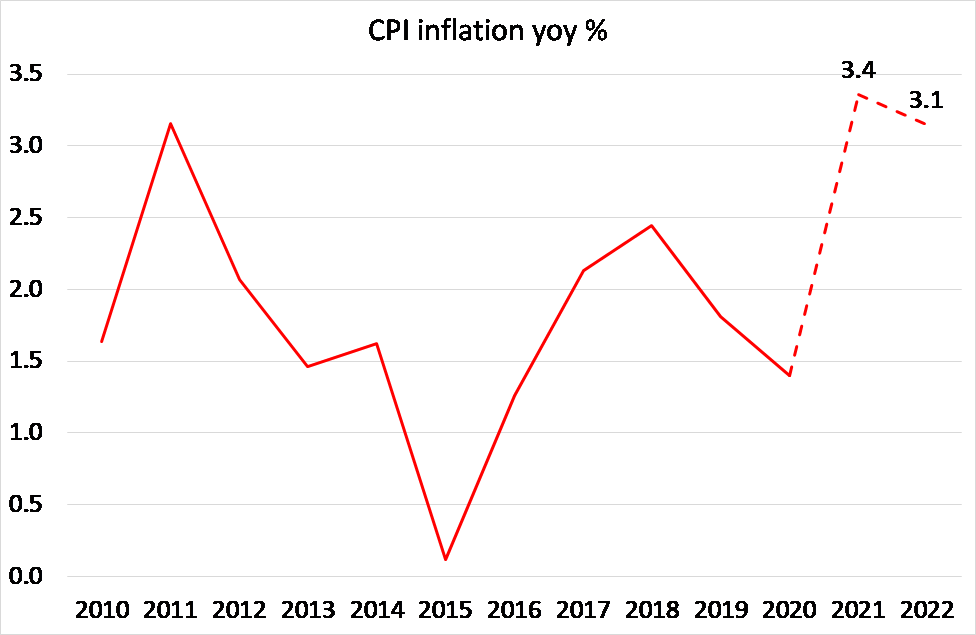

A Marxist model of inflation, which I have outlined before in a previous post, suggests that it is the movement of profits and investment demand along with money supply growth that will drive price inflation this year and next. So assuming sharp rises in profits and continued injections of money supply (if at a slower pace), this model forecasts US consumer inflation will go over 3% this year and next.

In the short term, inflation of goods and services could rise anyway because of ‘base effects’ (statistical blips), ‘supply chain’ disruption from COVID or so-called ‘pent-up demand’. But these factors are probably transitory, as the Fed Chair Jay Powell argues. But if inflation does go well above the Fed’s 2% annual target rate for some time, that could lead to a significant rise in yields (interest rates) on bonds, which are not under the control of the Fed. US Treasury secretary Janet Yellen, the former Fed chief, hinted that if inflation did pick up more than expected, the Fed would act to control it through ‘tighter’ monetary policy which would also drive up yields.

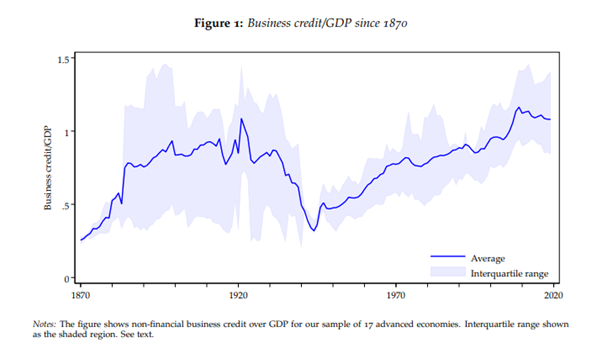

This raises the odds that weaker parts of the corporate sector in the major economies will get into difficulties and invoke a debt crisis. Remember: business debt relative to output is at its highest ever in the major economies.

In its recent Financial Stability Report, the US Federal Reserve warned that existing measures of hedge fund leverage “may not be capturing important risks”, pointing to the collapse of Archegos Capital as an example of hidden vulnerabilities in the global financial system. The Fed found that some asset valuations are “elevated relative to historical norms” and “may be vulnerable to significant declines should risk appetite fall”. In other words, a stock and bond market collapse is possible.

Borrowing cheap money hoarded by the banks to speculate on financial markets is called ‘margin debt’. According to the US Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, margin debt hit $822bn by the end of March — just after Archegos had failed. That was almost double the $479bn level of March 2020, when the pandemic lockdowns started and the Fed pumped in credit. And it’s far more than the around $400bn peak that margin debt reached in 2007, just before the financial crisis.

So any significant return of inflation in goods and services may bring down the house of cards that is the financial sector. What happens in the productive sectors of the capitalist economy still remains decisive.

Courtesy Michael Roberts Blog

Michael Roberts

Michael Roberts worked in the City of London as an economist for over 40 years. He has closely observed the machinations of the global capitalism from within the dragon’s den. Since retiring, he has written several books. The Great Recession – a Marxist view (2009); The Long Depression (2016); Marx 200: a review of Marx’s economics (2018): and jointly with Guglielmo Carchedi as editors of World in Crisis (2018). He has published numerous papers in various academic economic journals and articles in leftist publications.