This weekend, the leaders of the ‘free world’ are flying (and helicoptering) into Cornwall, at the tiny end of England, for the first physical meeting of the G7 nations. As they increase the carbon footprint sharply through extensive fossil fuel activity, the G7 agenda will include dealing with climate change, global ‘action’ on the COVID pandemic and the state of the world economy.

Crowding into the holiday resort of Carbis Bay, the G7 leaders will not be joined by the likes of China or Russia, who are excluded from the deliberations but as hosts to this jamboree, the UK has invited like-minded leaders from Australia, India, South Africa, and South Korea.

The leaders arrive as all the talk is of a fast-growing recovery in the major economies as they come out of the COVID lockdowns and vaccination rates rise. – According to investment bank JPM Morgan economists, “The global economy is on track for a boom in the current quarter, with the all-industry output activity index jumping to a new high and with continued robust gains in manufacturing joined by a stunning surge in services sector activity.” JPM reckons this points to near 5% annual growth in global GDP this year.

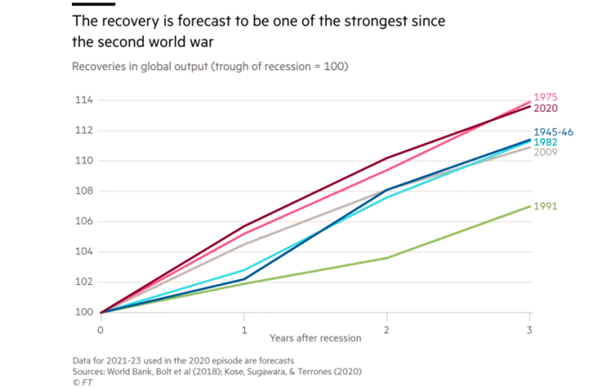

In its half-yearly outlook report, the World Bank forecast the world economy to grow at 5.6% this year, in a sharp upgrade from previous estimates it made in January of 4.1%. It said this would mark the fastest post-recession recovery in 80 years, with growth forecasts of 6.8% in the U.S. and 8.5% in China.

But these headlines hide the details. The World Bank is only projecting 2.9% growth among low-income countries, the slowest in the past 20 years (when setting aside the steep fallout of 2020). So the recovery is fuelled by growth in just a few major economies where rapid progress with the Covid-19 vaccine has enabled a faster return to relative normality. However, most ‘developing nations’ will continue struggling with the virus and its aftermath for longer, worsening divisions between rich and poor nations. Sounding the alarm over the uneven recovery, the World Bank said about 90% of rich nations were expected to regain their pre-pandemic levels of GDP a head by 2022, compared with only about one-third of low-income countries. This recovery is unusually narrow in per capita terms, with only 50 percent of countries expected to exceed their pre-recession peaks in 2022.

David Malpass, the bank’s president appointed under Trump’s presidency, said: “Globally coordinated efforts are essential to accelerate vaccine distribution and debt relief, particularly for low-income countries. As the health crisis eases, policymakers will need to address the pandemic’s lasting effects and take steps to spur green, resilient, and inclusive growth while safeguarding macroeconomic stability.”

But the Bank and the G7 leaders make no demand for the suspension of intellectual property rights by pharmaceutical companies to deal with supply shortages. Last month, the US backed a temporary suspension of such rights for Covid-19 vaccines, leaving the UK and the EU as the main opposition to such a move. Malpass said the World Bank did not support the lifting of IP rights because to do so could jeopardise spending on research and development. “The World Bank supports the licensing and transfer of technology to developing countries to bolster global supply,” he said. “A very critical part of the supply chain is the invention and creation of manufacturing techniques. Above all, as we go into the booster stage, it will be vital that [research and development] flows continue to increase so that we can create vaccines that apply to new variants.” Similarly, G7 host nation Britain is refusing to waive Covid vaccine patents. In other words, vaccines cannot be made and supplied unless big pharma makes a profit from it – no ‘people’s vaccines’ from the G7, even though much of research and development was funded by public money.

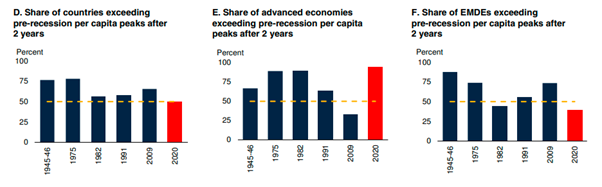

And what about global inequality? While hundreds of millions have been driven into poverty during the COVID pandemic slump, the extreme rich have got even richer.

And they continue to pay very little tax on their wealth. The richest 25 Americans reportedly paid a ‘true tax rate’ of 3.4% between 2014 and 2018, according to an investigation by ProPublica, despite their collective net worth rising by more than $400bn in the same period. It found that in 2007 Bezos, the founder of Amazon and already a billionaire, paid no federal taxes. In 2011, when he had a net worth of $18bn, he was again able to pay no federal taxes – and even received a $4,000 tax credit for his children. Last year, Bezos’s net worth topped $200bn. By contrast, the median American household paid 14% in federal taxes, ProPublica reported. The top income tax rate is 37% on incomes over $523,600 for single filers, having been reduced from 39.6% under Donald Trump.

ProPublica found that Buffett, founder of the investment firm Berkshire Hathaway, paid $23.7m in taxes from 2014 to 2018, on a total reported income of $125m. But Buffett’s wealth grew by $24.3bn, meaning he had a “true tax rate” of 0.1%. The rates expose the failures of America’s tax laws to levy increases in wealth derived from assets in the way wages – the prime source of income for most Americans – are taxed. Buffet commented “I continue to believe that the tax code should be changed substantially,” as “huge dynastic wealth is not desirable for our society”. But don’t worry, Buffett, said that 99% of his wealth will eventually go to philanthropy “during my lifetime or at death”. He added: “I believe the money will be of more use to society if disbursed philanthropically than if it is used to slightly reduce an ever-increasing US debt,” So the answer to grotesque wealth inequality is not even proper wealth taxes on the rich but instead to rely on their ‘good offices’ to spend their money where they can help. “The ultra-wealthy get to pick and choose when and how they’re taxed,” said one campaign group. “This is exactly why we need a strong, unavoidable wealth tax now.”

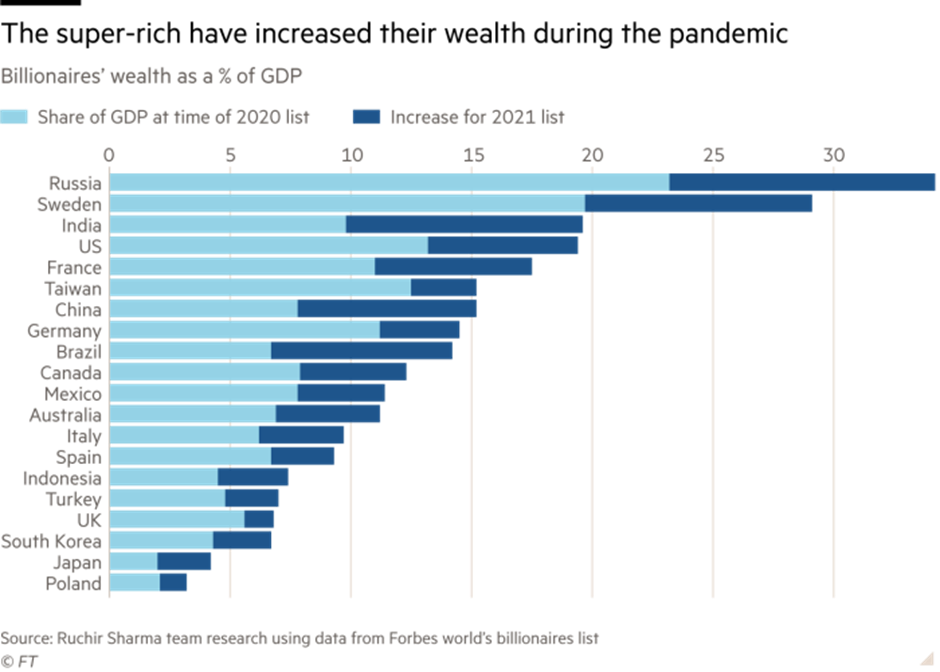

That brings us to the poster headline for the G7 meeting – the deal reached among G7 governments for a ‘global minimum corporate tax rate’, to be signed off at this week’s G7 meeting and then taken to the G20 summit later this year. The claim is that the deal will go some way to getting multi-national companies to pay tax where they make their profits rather than hiving them off to ‘tax haven’ countries.

But again, like the economic recovery, the devil is in the detail. The deal is far from the desperately needed overhaul of the global tax system and fails to limit the damaging use of tax havens – which are estimated to cost low-income countries $200bn each year. Under the deal it was agreed that G7 countries would set a minimum 15% corporate tax based on where the company made its sales, regardless of whether they had a physical presence in that country. But this agreement is full of holes.

First, most countries have higher rates than 15%, so it does not affect them. “It’s absurd for the G7 to claim it is ‘overhauling’ a broken global tax system by setting up a global minimum corporate tax rate that is similar to the soft rates charged by tax havens like Ireland, Switzerland and Singapore,” said Oxfam’s executive director Gabriela Bucher. “They are setting the bar so low that companies can just step over it.”

Second, the pact supposedly will make companies pay more tax in the countries where they are selling their products or services, rather than wherever they end up declaring their profits, thus curbing the use of tax havens by corporations. But that only applies to profit ‘margins’ above 10% and accounting tricks can ensure that breaking this threshold can be avoided. And anyway, only 20% of any margin above 10% will be reallocated.

Moreover, it seems that ‘sales’ will be defined as where they are exported not where they are consumed, thus hitting poorer countries and actually boosting profits to G7 nations. Ironically, a 15% minimum tax means that Biden in the US will now not proceed to raise corporate taxes in the US as originally promised!

As part of the deal, digital services taxes that have been introduced by several G7 countries to tax the mega tech companies will be dropped. TaxWatch, a think-tank, has calculated that Big Tech companies will pay less tax in the UK under the G7 plan than they currently do under the country’s digital services tax. Based on 2019 revenues, Amazon, eBay, Facebook and Google would pay £232.5m less in tax under the G7 plans. TaxWatch calculated that the tax take from Google would fall from £219m a year to £60m under the G7 plan. Facebook’s taxes would drop from £49m to £27.7m and eBay’s taxes would decline from £15.7m to £3.8m. TaxWatch added that eBay might even fall out of the scope of the G7 plan, which is designed to capture about 100 of the biggest global companies. As for Amazon, it currently pays £50m under the UK’s DST. It is not yet clear how it would be captured by the G7 plan, because its profit margins are below 10 per cent. TaxWatch estimated Amazon Web Services, its cloud unit, would pay £10.1m under the G7 proposals.

Then there are demands for exemptions that could scupper any tax revenues for governments. UK wants an exemption on financial services. And Paris, Berlin, Copenhagen and Luxembourg are also trying to persuade the EU commission support exemption for their banks.

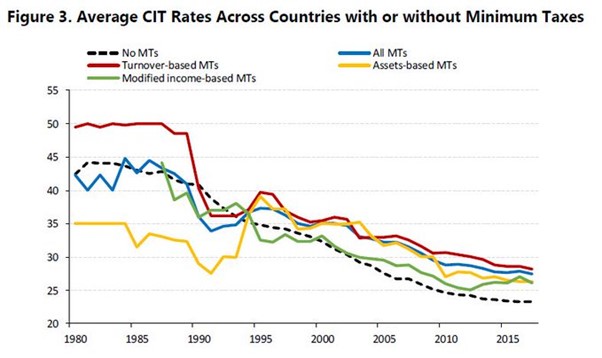

This deal will do little to reduce inequality and establishing fairness. The IMF chart below groups together 196 countries with the same type of corporate income tax (CIT) system (there are several) & if a minimum tax (MT) rate is used. It shows that, even if some minimum international level had been set back in the 1980s, tax levels would still be way below levels in the 1980s, minimum or no minimum.

It is not higher corporate taxes that are needed; it’s ownership and control of the multi-nationals and the closure of tax haven operations. Of course, there is no G7 deal on that.

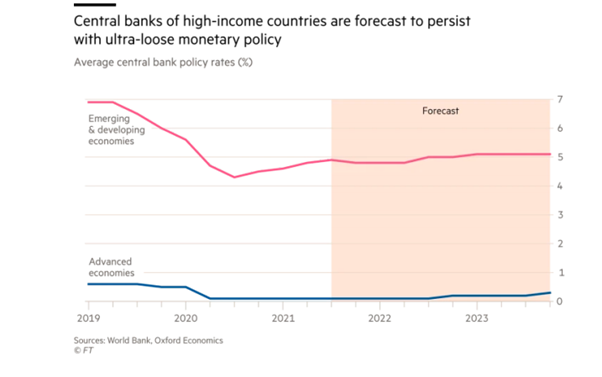

Economic recovery may be under way now as businesses reopen, fiscal spending is boosted and monetary largesse from central banks continues, but this is really only creating what some have called a ‘sugar-rush economy’.

And even on these criteria, emerging and developing countries are far behind. Quantitative easing has averaged 15 per cent of GDP in high-income countries against 3 per cent in emerging and developing countries. Fiscal support averaged 17 per cent in high-income countries against 5 per cent in emerging and developing countries.

Moreover, half of all low-income countries are in debt distress. And the record level of debt around the world, particularly among emerging and developing countries, is a threat to economic stability as global financial system is now vulnerable to a sudden increase in interest rates. But the G7 will do nothing about debt cancellation.

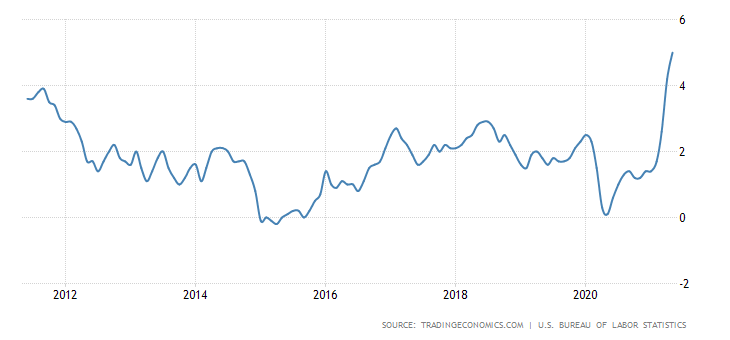

The risk of significant consumer price inflation is rising as bottlenecks in global supply chains build up. US consumer price inflation rate jumped to 5% in May, the highest rate since August 2008 due to soaring commodity prices, supply constraints, and higher wages. The core index jumped 3.8% in May, the largest increase since June 1992.

There could be stronger inflation over the next six to 12 months, especially in import prices and if international supply chains are weakened, we could see a rise in prices over a period of time. Inflation in the late 1980s was immense. In most advanced countries, it was in the double-digit percentage range. Over the last two decades, inflation in these countries has, broadly speaking, been around 2%. But we could see the inflation rate for the next 12 months between 3-4% until production can catch up with increased demand.

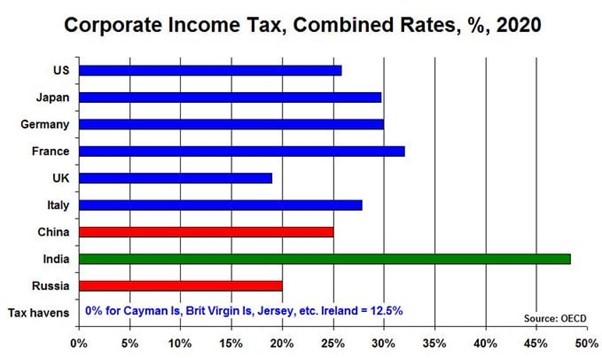

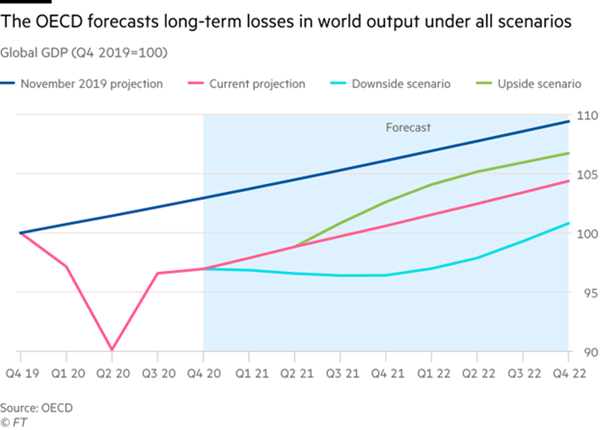

Indeed, it is likely that after the initial burst of economic expansion after the end of COVID pandemic this year and into next, the world economy, led by the G7 nations, will fall back into the previous crawling pace of economic growth experienced before the pandemic. That will mean that most major economies will not return to even the previous trajectory of weak real GDP growth (the blue line in the graph below).

The global economy was already growing very weakly in 2019. That’s because capitalism grows sustainably and strongly only if profitability increases. However, average profitability was already very low before the pandemic, and in some countries, it was at the lowest level since the end of the Second World War.

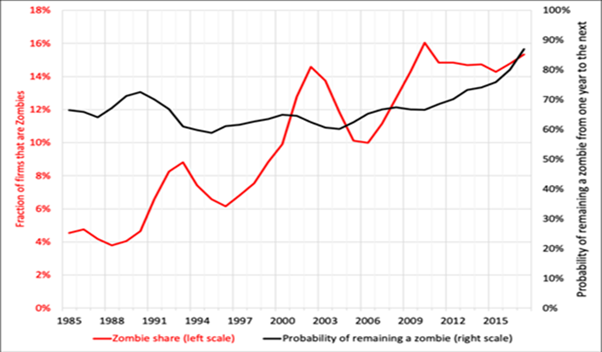

Profitability would only revive if some rotten layers of capital were removed in what is called ‘creative destruction’ of the weak to help the strong. Instead, up to now, cheap money and fiscal support have kept alive the ‘living dead’, so-called zombie companies, which make little profit and can only just cover their debts. In the advanced economies, about 15-20 percent of companies are in this situation. These companies keep overall productivity low, hindering the more efficient parts of the economy from expanding and growing.

And what if they should collapse? These zombies are “a ticking time bomb” whose explosive effects will be felt if governments and central banks withdraw measures that have helped keep them alive during the pandemic.

Apart from restoring profitability and investment long term, the other challenge facing the G7 leaders is global warming and climate change. A recent UN report found that far too little was being done and funded to save the planet. Out of the $14.6 trillion the world’s 50 largest economies announced in fiscal spending in the wake of COVID-19, just $368 billion (or 2.5 per cent) was being directed towards ‘green initiatives’. That needs to at least triple in real terms by 2030 and increase four-fold by 2050 if the world is to meet its climate change, biodiversity and land degradation targets, says the UN. This acceleration would equate to cumulative total investment of up to USD 8.1 trillion and a future annual investment rate of USD 536 billion. The UN hopes that private investment will step up tot the plate. Fat chance! Up to now, of $133 billion/year invested in ‘nature based solutions’ to global warming public funds make up 86 per cent and private finance 14 per cent.

There is little chance that G7 nations will add to this. And the G7 has no intention of reducing subsidies to fossil fuel industries, let alone bringing them into public ownership in order to plan the phasing out of these carbon emitting companies. Instead, heavily subsidized private oil companies enjoy the profits of oil extraction while the rest of us pay in tax dollars, human rights abuses and an unliveable climate.

Of course, public ownership by itself does not guarantee that we can fully replace oil and gas with renewable energy in time to avert the worst impacts of the climate crisis. After all, three-quarters of the world’s oil reserves are already owned by states rather than private companies. But if companies like Shell or ExxonMobil were nationalized with a mandate to wind down their assets, it would be a start.

Instead, the G7 as the globe’s imperialist bloc is much more interested is finding ways of isolating China and Russia in order to maintain its hegemony. The problem for the G7 is that, whereas in the 1970s the G7 nations accounted for some 80% of world GDP, that is now down to about 40%.

Courtesy Michael Roberts Blog

Michael Roberts

Michael Roberts worked in the City of London as an economist for over 40 years. He has closely observed the machinations of the global capitalism from within the dragon’s den. Since retiring, he has written several books. The Great Recession – a Marxist view (2009); The Long Depression (2016); Marx 200: a review of Marx’s economics (2018): and jointly with Guglielmo Carchedi as editors of World in Crisis (2018). He has published numerous papers in various academic economic journals and articles in leftist publications.