The G7 leaders meet this weekend in Hiroshima, Japan, the site of the first atomic bomb holocaust dropped by American bombers on the city in August 1945, leading to the deaths of at least 100,000 citizens. But the G7 leaders’ main deliberations will not be about that, but instead on how to ‘contain’ China and ‘protect’ Taiwan from Chinese ‘aggression’ through further militarization of the island as a thorn in the side of Chinese leaders. It’s a form of what the British police call ‘kettling’, namely to surround and contain demonstrators in public protests. It is no accident that, with the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) is now expanding its role into Asia, that Ukrainian leader Zelensky has been invited to address the G7 leaders. As a counter, the Chinese are holding a conference of central Asian states in Xian. Such are the machinations of the intensifying geo-political conflict.

But this blog deals with economics and the G7 meeting is an opportunity to consider the state of world economy five months into 2023. My post last December on the economic prospects for 2023 was entitled “the impending slump”. And I said that “Never has an impending recession been so widely expected. Maybe that means it won’t happen – given the record of mainstream economic forecasters! But this time the consensus looks set to be right.”

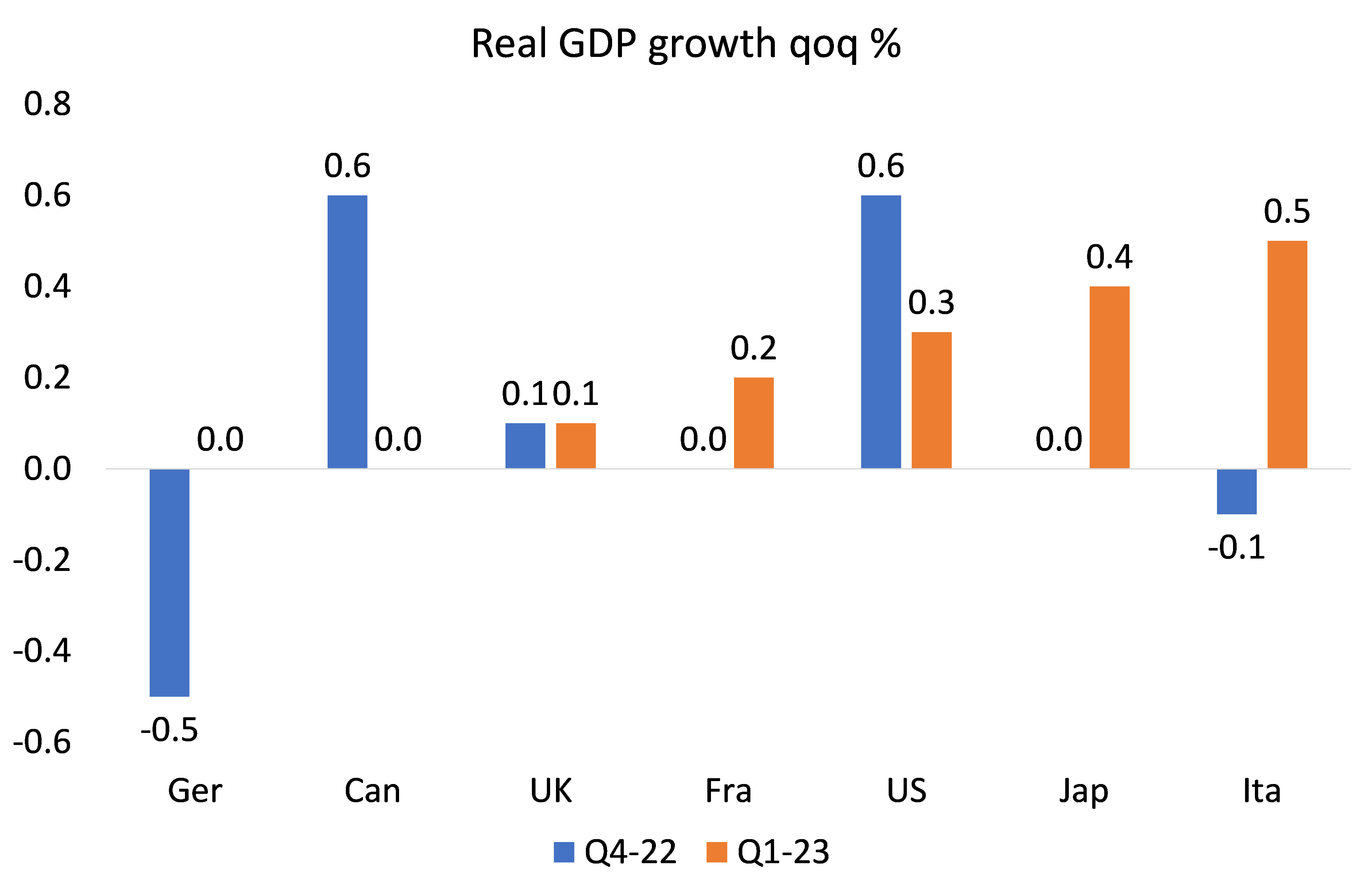

Well, five months in and there has been no slump – at least, not by the very crude definition of mainstream economics of a ‘technical’ recession, where an economy’s real GDP contracts for two successive quarters. Several G7 economies have been pretty close to meeting that criterion of a slump: Germany and Italy recorded a contraction in Q4-22; Germany and Canada stagnated in Q1-23 and the UK barely grew in both quarters. France was not much better and the US, the best performing G7 economy, halved its growth rate in Q1-23.

The US National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is the body usually referenced to decide whether there is a slump in the US – its criterion covers many more economic indicators. Here is how the NBER defines it:

“Because a recession must influence the economy broadly and not be confined to one sector, the committee emphasizes economy-wide measures of economic activity. The determination of the months of peaks and troughs is based on a range of monthly measures of aggregate real economic activity published by the federal statistical agencies. These include real personal income less transfers, nonfarm payroll employment, employment as measured by the household survey, real personal consumption expenditures, wholesale-retail sales adjusted for price changes, and industrial production. There is no fixed rule about what measures contribute information to the process or how they are weighted in our decisions. In recent decades, the two measures we have put the most weight on are real personal income less transfers and nonfarm payroll employment.”

So the NBER’s definition of a slump is more judgement than a rigid set of indicators. Most important of those is whether real personal incomes are rising or falling and whether employment is rising or falling. In the last two quarters, US real personal income rose 0.2% in Q4-22 and just 0.05% in Q1-23 (that is basically flat). So no contraction there yet, but slowing nearly to a halt.

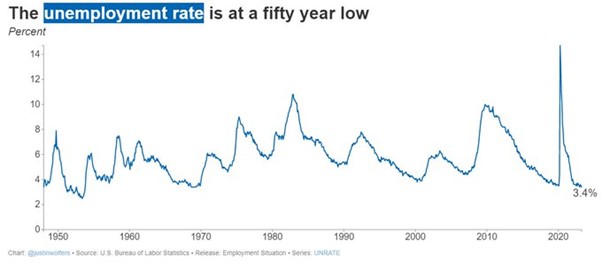

As for employment, although slowing in growth through much of 2022, employment rose by 0.6% in Q4-22 and at the same pace in Q1-23. Indeed, much is made of the low unemployment rates in the US and the rest of the G7. In the US, the rate is at a 50-year low. And it’s the same story in the other G7 economies, if at different levels.

However, both these key NBER indicators are lagging indicators of a slump. They are confirmations of a slump already in progress. Rising unemployment and falling incomes only happen when a slump is underway, which is why the NBER uses them. But these indicators are no guide to whether there is “an impending slump”. Under capitalist production, if companies are reducing investment and laying off their workforce and so reducing the overall wage bill, sales revenues will have been falling and profits declining well before that. So we must look elsewhere for leading indicators.

Marxist economic theory suggests that slumps will happen when the profitability of capital starts falling; eventually leading to a fall in total profits in an economy. Those profits can further be squeezed by increases in the cost of capital i.e. interest costs on borrowing.

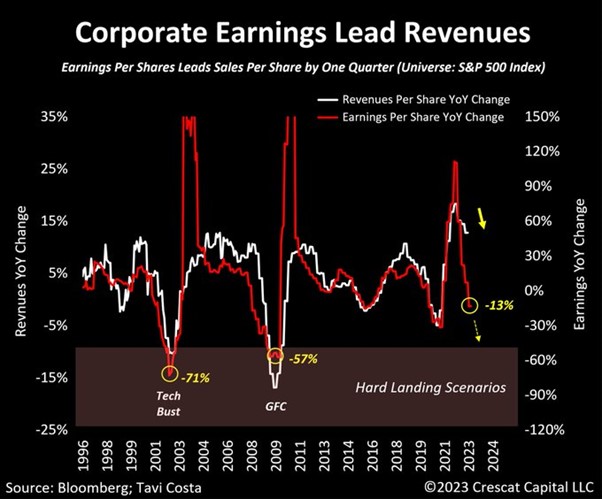

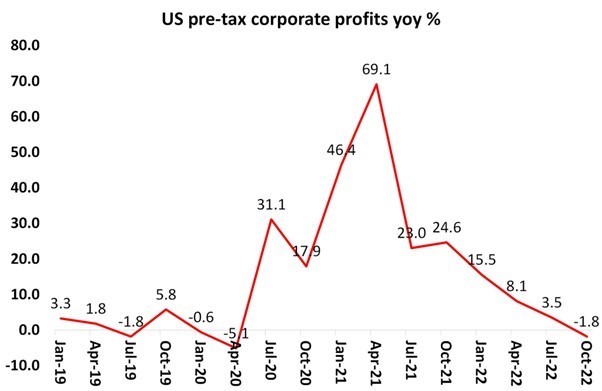

And on these criteria, the signs are rising of an impending slump. US corporate profits are suffering the biggest downturn in seven years. With the Q1-23 corporate earnings season over, the profits of S&P 500 companies are estimated to have dropped 3.7% on average compared to a year ago. This is the second straight quarter of earnings declines and forecasts for the current Q2-23 that we are now in is for a further fall of 7.3%, with no better in Q3-23. This suggests a longer profit recession than during the pandemic. An earnings drop of more than three quarters was last seen in 2015-16, when the Federal Reserve started its last interest-rate hiking cycle.

According to historical data, changes in earnings tend to precede changes in sales revenue by approximately one quarter. As corporate earnings have fallen 13% in the last two quarters, we can expect sales revenues to follow.

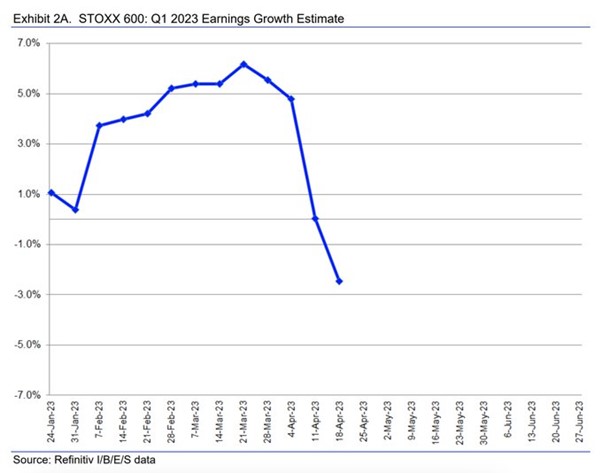

The corporate profit drop is not confined to the US. In Europe, estimates for corporate earnings are for a fall of 2.5% yoy in Q1-23, 5.4% in Q2-23 and 7.4% in Q3-23.

In previous posts I have pointed out that all the recent talk (understandable) of record high corporate profits and the hiking of margins as the main cause of rising inflation is now out of date. If the current cost of living crisis starting in 2022 was caused by ‘greedflation’, as some argue, it won’t be the case during 2023.

Profit margins (profit per unit of production), having reached historic highs last year, are falling back and total corporate profits are now going south. In Q4-22 non-financial corporate profits fell 5.4%.

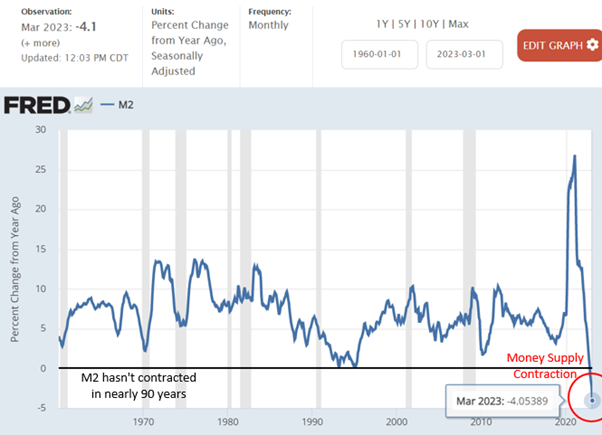

Then there is the rising cost of borrowing to fund production and investment as the Fed and other central banks hike interest rates and tighten credit at an unprecedented pace, supposedly to ‘control’ inflation in prices. US money supply is contracting for the first time in 90 years.

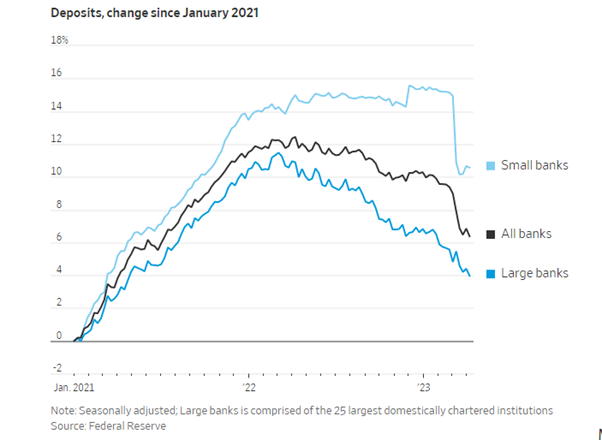

The result of these interest-rate rises has been a smouldering banking crisis in the US and Europe, as smaller and weaker banks become insolvent because the value of their assets in bonds have dropped sharply and depositors have fled to better yielding institutions or because companies and households need to spend their savings to meet rising bills.

Higher funding costs for banks will squeeze profits. Economists at Goldman Sachs estimate every 10% decline in bank profitability reduces lending by 2%. If the share of Fed interest-rate changes that are passed on to bank deposit rates, sometimes called “deposit betas,” reach levels seen in 2007—the last time the Fed raised rates close to current levels—that could lead to a 3-6% decline in lending in the US. Goldman expects that could reduce economic output by 0.3-0.5 percentage points this year, pushing the economy into recession.

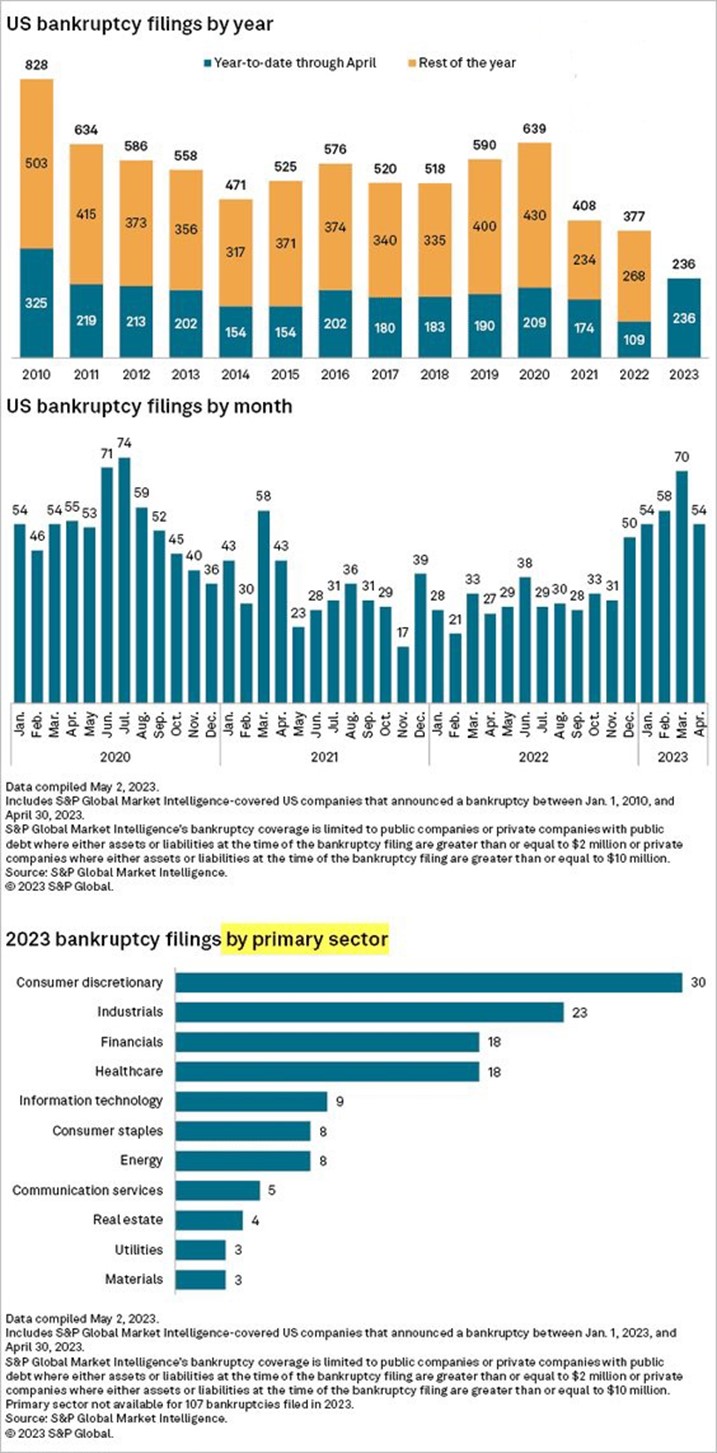

That’s the banks. Behind them is the growing crisis in non-financial companies. Since 2000, non-financial corporate debt across America and Europe has grown from $12.7trn to $38.1trn, rising from 68% to 90% of their combined GDP. The rising costs of servicing this debt is pushing the weaker corporate ‘zombies’ and ‘fallen angels’ into bankruptcy.

Whether the major economies go into an outright slump in 2023 is a moot point. Economic growth will be feeble at best, while ‘sticky’ inflation rates reduce real wage growth to very low rates (or into continued falls). In the US, the average decline in real wages was just over 2% year-on-year in the third quarter of 2022. In Europe, Germany and Spain saw even more pronounced declines in purchasing power, with real incomes falling by just over 4% and 5% respectively. Real wages in the Eurozone have fallen by 8% since the end of the pandemic slump in 2020. In Germany, real earnings have plunged by 5.7% in the last year, the largest real wage loss since statistics began.

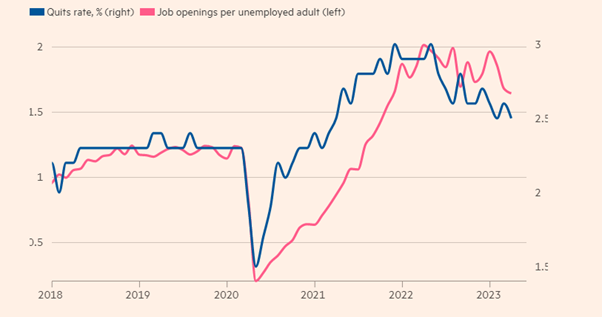

And there are signs too that the ‘hot’ labour market is cooling. The post-Covid expansion of jobs (if mainly low paid and part-time) saw high vacancy and quit rates in the US. They are now dropping, if still above pre-pandemic levels.

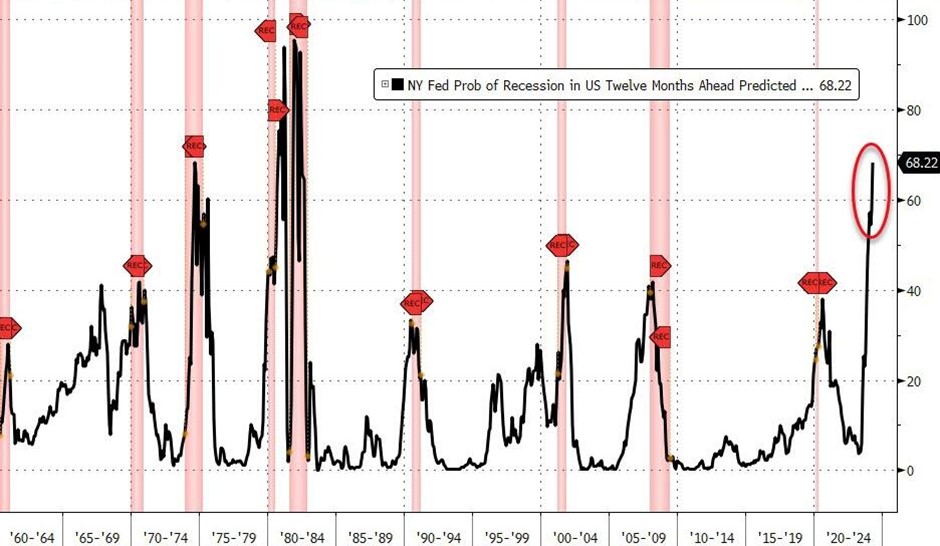

The odds that the US will fall into a recession at some point over the next 12 months have risen to a 40-year high, according to a probability model from the New York Federal Reserve. The probability that the country will enter a recession within the next year has risen to 68.2 percent, which is the highest level since 1982. Indeed, the Fed’s recession risk indicator is now greater than it was in November 2007, not long before the subprime crisis, when it stood at 40 percent.

What won’t be discussed at the G7 meeting this weekend is the accelerating debt and currency crises in the Global South. I have reported on this before and will return to the issue in another post. But that debt disaster will ensure that any slump in the G7 economies will spread quickly to the rest of the world.

Michael Roberts

Michael Roberts worked in the City of London as an economist for over 40 years. He has closely observed the machinations of the global capitalism from within the dragon’s den. Since retiring, he has written several books. The Great Recession – a Marxist view (2009); The Long Depression (2016); Marx 200: a review of Marx’s economics (2018): and jointly with Guglielmo Carchedi as editors of World in Crisis (2018). He has published numerous papers in various academic economic journals and articles in leftist publications.