It’s common today to hear pundits declare that the U.S. is facing an “unprecedented” crisis of democracy.

Liberals at the MSNBC network have banged on for years about how “Russian interference” in the 2016 and 2020 presidential election poses an existential threat to U.S. democracy and sovereignty.

At a speech at George Washington University in September, Sen. Bernie Sanders said about the 2020 presidential election: “This is not just an election between Donald Trump and Joe Biden. This is an election between Donald Trump and democracy – and democracy must win.”

And the main strategy to “save” U.S. democracy from “fascism,” they argue, is to vote for Joe Biden and a Democratic Congress: “blue no matter who.”

There are plenty of reasons to lament the state of democracy, even in the limited form—elections, legislatures, courts, and the rest—that it is exercised in the U.S. today. But many of the liberal critics make it seem as if the main threat to U.S. democracy is Trump or his Russian paymasters.

Yet even by a definition of democracy that has pretty low standards—relatively free and fair elections, where voters can participate with little threats to their personal safety—only about 12% of the world’s people are considered to be living under “full democracy,” according to the 2010 Economist intelligence unit’s Democracy Index. Three times as many of the world’s people live in Authoritarian regimes, as the EIU defines them.

In 2010, the U.S. ranked 17th in the list of “full democracies.” In 2020, the U.S. had dropped to 25th place and out of the ranks of “full democracies” to the ranks of “flawed democracies,” behind “full democracies” South Korea, Spain, Portugal and Chile—all of whom emerged from military dictatorship in the last generation.

Trump is certainly a tinpot authoritarian wannabe. But we only have to ask ourselves how he got to where he is now to uncover the true crisis in U.S. democracy. In 2016, Trump eked out a close victory in the Electoral College while losing the popular vote by over 2 million votes. He was the second Republican president in this century to “win” while getting fewer votes than his opponent.

In fact, Trump’s election in 2016 marked the fifth time in U.S. history that the presidential winner got fewer votes than the loser.

This wasn’t a fluke. It was by design, and it goes right back to the founding documents of the U.S. republic.

The Constitution that both liberals and conservatives venerate was, in fact, not much more than a pact between the leading merchants and slaveholders in the early U.S., designed to cement the rule of an elite for perpetuity.

The U.S. Declaration of Independence from Britain in 1776 uses some fairly radical language: “all men are created equal”; governments derive “just powers from the consent of the governed”; “the right of the people to alter or to abolish” government, and so on. The colonial elite used this sort of rhetoric to mobilize the broader mass of the population to cast their lot with independence from Britain.

But the founders, mostly drawn from the leading merchants and plantation owners, weren’t about to turn their newly independent state over to artisans and farmers. One of the most class conscious of them, Alexander Hamilton, the first treasury secretary and main writer of the Federalist Papers, a series of popular essays justifying the Constitution, put it pretty succinctly: “that power that holds the purse strings absolutely must rule.”

However, given that the colonial population had fought a revolution to win independence, the founders realized that it was impossible to simply junk democracy. So, they came up with a system under the constitution that institutionalized the role of the rich and “well-born” to control the passions of what they quite often referred to as “the Mob.” The formula enshrined in the Constitution was that of “Representative Government,” where the people would vote for a limited number of representatives, but where the representatives would be chosen from the ranks of the rich.

Hamilton made this explicit in Federalist Paper #35, where he argues that “artisans and mechanics” (18th century terminology for workers) will be inclined to vote for “merchants and those whom they recommend” as their “Natural patron or friend.” And the fact that the merchant must be elected is enough to keep them true to the interests of ordinary people.

The other key point that concerned the founders was to make sure that the government did not provide opportunities for the mass to unite to threaten the property of the few. One of the events that precipitated the colonial elite to scrap the original weak government of the Articles of Confederation and replace with the strong federal government implied in the Constitution was Shay’s Rebellion, an armed uprising of western Massachusetts farmers against confiscation of their property to pay state debts.

General Henry Knox, writing to George Washington, said of the rebels: “Their creed is that the property of the United States has been protected from the confiscation of Britain by the joint exertions of all, and therefore ought to be the common property of all.” “This dreadful situation has alarmed every man of principle and property in New England,” Knox continued. “Our Government must be braced, changed, or altered to secure our lives and property.”

Knox’s comments may have been alarmist, but much of the constitutional convention and many of the Federalist papers are taken up with this question of preventing the majority from asserting its will. And judging by their results, the founders were largely successful.

They created a system in which, initially, only one part of the government (the house) was directly elected. Until only about 100 years ago, states appointed U.S. senators. The senate was meant to include the leading citizens of the state who would cool the passions of the mob in the House. Today, U.S. voters still don’t directly elect the president.

The structure of the government is set up to fragment power, with two houses of Congress, elected at different times, for different terms. With powers divided between localities, states, and the federal government. With power divided between executive, legislative and judicial branches. All of this aimed, as James Madison put it in Federalist #10 to guard against, among other things, “A rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property, or for any other improper or wicked project.”

Perhaps left unsaid here was the key “improper or wicked project” that ultimately amounted to the largest expropriation of wealth in U.S. history: the abolition of slavery. Madison, of course, hailed from the Virginia elite whose economic and political power was based on chattel slavery.

For this reason, other features of the U.S. system, such as the Electoral College and the equal representation of states regardless of size or population in the U.S. Senate—even the state-based regulation of voting in federal elections—represented “compromises” with the slave power that even the Civil War didn’t eliminate.

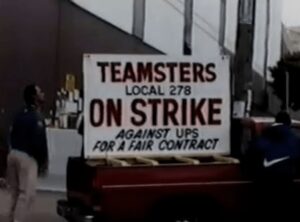

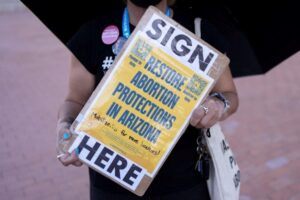

This of course isn’t the end of the story of democracy in the U.S. The range of democracy has been expanded through mass struggle, the most important of which is the overthrow of slavery, the agitation for women to win the right to vote, the struggle for referendum, the recall and the direct election of senators from the Populist and Progressive movements, and the fight for union rights in the 1930s and for civil rights in the 1960s.

It’s only through these struggles—most often in opposition to the ruling class and “well-born” people—that the range of formally recognized democratic rights in the U.S. was widened beyond what the founders intended. Nevertheless, the results of the 2000 and 2016 presidential elections, where the loser of the popular vote, “won” the election should be a reminder that the structure of the US government remains biased against the majority and biased toward conservatism.

James P. Cannon, one of Founders of American Trotskyism, once said that “[Socialists] should recognize [the worker’s] demand for human rights and democratic guarantees, now and in the future, is in itself progressive. The socialist task is to not to deny democracy, but to expand it and make it more complete.” He added: “in the United States, the struggle for workers’ democracy is preeminently a struggle of the rank and file to gain democratic control of their own organizations.”

That’s the important point. The periods in U.S. history when democratic rights have been expanded are the same periods when masses of people were organizing to fight for their own interests. They were engaging in the process of “gaining democratic control” over their own organizations, training thousands of ordinary people to become activists on their own behalf.

The great peoples’ historian Howard Zinn (a recent target of Trump’s rantings) put it well:

“The Constitution gave no rights to working people; no right to work less than 12 hours a day, no right to a living wage, no right to safe working conditions. Workers had to organize, go on strike, defy the law, the courts, the police, create a great movement which won the eight-hour day, and caused such commotion that Congress was forced to pass a minimum wage law, and Social Security, and unemployment insurance….Those rights only come alive when citizens organize, protest, demonstrate, strike, boycott, rebel and violate the law in order to uphold justice.”

That’s a lesson that our movements need to take to heart, no matter who sits in the White House or on the Supreme Court.

Lance Selfa is the author of The Democrats: A Critical History (Haymarket, 2012) and editor of U.S. Politics in an Age of Uncertainty: Essays on a New Reality (Haymarket, 2017).