For forty-two years, the International Socialist Organization (ISO) was the main vehicle for the politics of International Socialism in the U.S. The ISO attempted to preserve the revolutionary socialist tradition (the self-emancipation of the working class), while linking the fight against all forms of oppression to the fight against exploitation. The ISO survived and even managed to advance in a political era that witnessed the disappearance of many other revolutionary organizations in the U.S.

Why then, did the ISO dissolve itself earlier this year—in a process that took place in the months before, during and after its convention in February 2019?

This document puts forward an analysis that describes a different viewpoint from the dominant narratives that have circulated around the Internet as to how and why the ISO devoured itself in such a short period of time—many of which blamed the ISO’s demise on a crisis arising from an alleged “rape coverup” six years ago. This (false) accusation emerged weeks after the February convention, but the targets were the same grouping of long-standing comrades who had already been pilloried at the convention. We were called the “SC Minority” only because the self-proclaimed “SC Majority” had decided to marginalize us for political reasons.

The Steering Committee Majority (“SC Majority”) structured the ISO’s 2019 February convention as an entirely internalized event, dubbed an “internal reckoning.” The name “Trump” was barely mentioned during the three-day meeting, while the wrath that comrades normally reserve for our ruling class enemies was instead directed at other ISO members—specifically at some of us who had built the organization from its beginning. To those of us on the receiving end of this abuse, the convention had the flavor more of a show trial than a flowering of democracy. It wasn’t clear why we were targeted for such hostility, since all of us had already declined to run for any leadership position specifically to avoid a destructive faction fight that could harm the organization.

Simply put, the SC Majority set the wheels in motion for the circular firing squad that rapidly consumed the ISO. A section of the ISO leadership aimed to advance itself (and its rightward political course) by destroying those who would stand in its way. The SC Majority cynically employed identity politics in one of its most primitive and damaging forms—known as “callout culture” or “privilege checking”—to achieve its objectives. But that tactic backfired, badly. While Jen R. and Todd C. from the SC Majority promised in a pre-convention document that their strategy for growth would recruit “hundreds and hundreds” of new members, the exact opposite occurred within a matter of weeks after the February convention, as the ISO began hemorrhaging members before the allegations of a rape coverup emerged. By the end of March, the remaining members (and many ex-members, who were invited to participate) voted to dissolve the organization entirely.

This document is written not to claim that the historic leadership of the ISO has been perfect (far from it) but rather to contest the notion that we were the devil incarnate. All human beings make mistakes, and we made plenty. We believe that our main “crime” in the eyes of our SC opponents was defending the set of fundamental politics that our organization (and the revolutionary left in the U.S. historically) was founded upon, i.e. loyalty to the political principles that guided those politics. In recent years, our leadership bodies became increasingly divided as some, in our opinion, accommodated to liberalism and social democracy, and more recently, identity politics. This assertion requires a certain amount of background to explain the ISO’s crisis.

The rise of a new social democracy in the U.S.

The rise of social democracy (albeit of the peculiar U.S. variety) has been a welcome development after decades of a shrinking and embattled socialist left, and retreat and setbacks for the working-class struggle. The growing popularity of “socialism” as an alternative to “capitalism,” especially among young people (measured through opinion polls) was initially a response to the massive class and social inequality produced by the Great Recession of 2008. As the economy recovered and entered a boom in the years that followed, corporate profits soared yet income inequality grew, and more and more young people have been drawn to the need for a socialist alternative. Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign was a result of already leftward moving consciousness, but it also served to inject new confidence in building a socialist project.

At the same time, U.S. society has also become increasingly polarized between the right and left. The politics of right-wing populism have gained a hearing more broadly, and Trump cohered a nationalist and xenophobic following during his 2016 campaign. Trump’s election to the presidency helped to fuel a revival of the organized far right, including its fascist elements, polarizing U.S. society yet further.

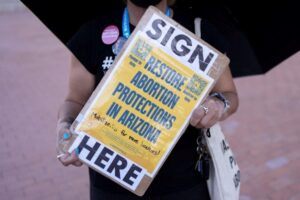

Trump’s election introduced a new sense of urgency to building a socialist alternative, and the DSA grew from a long-standing but small organization to the large and vibrant force (numbering more than 55,000) it has become today. The DSA has broken from the margins of U.S. politics into the mainstream, as prominent elected officials such as Congressperson Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have succeeded in changing the national conversation on a range of subjects, including the Green New Deal. This is, of course, an extremely positive and long-awaited development.

Unfortunately, however, the DSA today has not broken as an organization from a strategy of working to elect candidates running inside the Democratic Party—one of the two ruling class parties that together run the U.S. electoral system. The Democrats and Republicans have a long-standing power sharing agreement that has thus far prevented all but a few third-party challengers from even gaining ballot access. Sanders, a self-declared “independent,” chose to run as a Democrat in 2016 and is again doing so in 2020. Likewise, Ocasio-Cortez and other DSA members who were elected last November ran as Democrats and operate within the confines of the Democratic Party.

The pull of the Democratic Party and the ISO

The Democratic Party is a far cry from a labor or social democratic party. It operates in the interests of the corporate class, just less stridently than the Republicans. The differences between the Republican and Democratic parties are far smaller than what they share in common. But the Democratic Party’s softer rhetoric has historically allowed it to absorb social movements into its fold, not to advance them but to disarm their radical elements. For this reason, the U.S. revolutionary left has historically referred to the Democratic Party as “the graveyard of social movements.” The class composition of today’s resurgent Democratic Party is no different from that of its heydays of the past: led by an elaborate pro-corporate machine but supported by progressives as the lesser of the two “evils” on offer.

Had Sanders run as an independent rather than a Democrat in 2016, the ISO would not have hesitated to support and enter his campaign, whatever our criticisms of his politics.

Understandably, many ISO comrades became frustrated that the ISO did not join the Sanders campaign and those of other democratic socialists running as Democrats. In the short term, the meteoric rise of DSA made the ISO seem irrelevant compared to the much larger DSA in the eyes of a significant layer of ISO comrades. These are valid concerns, and a variety of opinions were debated on these subjects in SocialistWorker.org and pre-convention bulletins over a period of eight months before the ISO’s February 2019 convention. (This willingness to debate our differences has long been a practice in the ISO.)

Within the ISO SC, a shadow debate emerged but was never fully or explicitly spelled out. Instead, the SC Majority chose to adapt to this pro-Democratic Party sentiment—while deriding as “sectarian” and “defensive” those of us who reasserted the revolutionary left’s long-standing principle of non-participation in the Democratic Party.

It was not until well after the ISO’s February convention, on March 15, that the newly elected SC issued a revealing statement on the “actions” it would undertake, published at SocialistWorker.org: “[Forming an] Elections Committee to support independent candidates and ballot initiatives, and study how the ISO can relate to socialist campaigns run on Democratic ballot lines.” [Emphasis added.] In this way, the new SC slid further toward support for Democratic Party candidates after the February convention.

To us, the debate over support for Democrats involved the only political principle at stake among all of the issues up for consideration at the convention. That discussion could have been fair and productive, with the convention’s elected delegates voting on a clear resolution one way or the other. But the SC Majority and the other leading currents explicitly argued against such a resolution at the convention.

In the months leading up to the February convention, the SC Majority chose to rally its troops not through political argument aimed at resolving the ISO’s position on Sanders and other socialists running as Democrats but rather through a rumor mill that worked overtime, often amounting to character assassination—with the sole purpose of marginalizing this small number of long-standing members it labeled as the “SC Minority.” The problem with rumors is that they take place behind the scenes, which prevents their targets from challenging their accuracy —and when repeated often enough, such rumors then parade as “facts.” The bits of gossip that made their way to us were appalling, but none of them appeared in any of the 45 pre-convention bulletins that were published ahead of the convention.

Nevertheless, the rumors and gossip achieved their purpose well before the convention even took place: vilifying long-standing members of the leadership as “bullies” who “shut down debate,” maintaining an “undemocratic culture” which was claimed to be “toy Bolshevism.” The ISO was caricatured as emblematic of the “Trotskyist ghetto,” satisfied with its isolation—contrary to everything the ISO has stood for in its history, reaching out to anyone and everyone willing to struggle alongside us. In our eyes, our main offense was our willingness to engage in sharp argument when major issues were at stake. One aspect of women’s oppression is that strong and confident women are often derided as “b****es.” This sexist trope has been used to claim that I was key in fomenting the allegedly “toxic” culture of the ISO—because I confidently argued for the working-class politics that were foundational to the ISO.

One might reasonably ask why these rumors held sway among so many members before, during and after the February convention. The reason is straightforward: the SC Majority replaced the so-called “undemocratic culture” of the ISO with “callout culture”—which is much less democratic and far more toxic than anything that came before. We are far from alone in our opinion about callout culture, which is shared by many activists concerned with building movements that are as broad and united as possible. Widely respected Black feminist scholar and activist Loretta Ross published a New York Times op-ed on August 17, 2019 titled “I’m a Black Feminist. I Think Call-Out Culture Is Toxic.”

Ross wrote,

Call-outs happen when people publicly shame each other online, at the office, in classrooms or anywhere humans have beef with one another. But I believe there are better ways of doing social justice work…

But I wonder if contemporary social movements have absorbed the most useful lessons from the past about how to hold each other accountable while doing extremely difficult and risky social justice work. Can we avoid individualizing oppression and not use the movement as our personal therapy space? Thus, even as an incest and hate crime survivor, I have to recognize that not every flirtatious man is a potential rapist, nor every racially challenged white person is a Trump supporter…

I believe #MeToo survivors can more effectively address sexual abuse without resorting to the punishment and exile that mirror the prison industrial complex. Nor should we use social media to rush to judgment in a courtroom composed of clicks. If we do, we run into the paradox Audre Lorde warned us about when she said that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

We can build restorative justice processes to hold the stories of the accusers and the accused, and work together to ascertain harm and achieve justice without seeing anyone as disposable people and violating their human rights or right to due process. [Emphasis added.]

“Callout culture” and anarcho-liberalism

As Ross describes, callout culture has dominated the activist left for several generations running in the U.S. The results are usually disastrous for organizations of every stripe, conducive not to building broad movements but to splits and dissolution, as activists within the same organizations call attention to potential divisions between them rather than building upon the common interests that unite them. Callout culture has much more in common with postmodernism than Marxism, with an emphasis on language, individual “differences” and “microaggressions” (interpersonal behaviors), which in practice supersede the importance of fighting the system as a whole.

There is a common ritual involved in callout culture: First, a specially-oppressed person or persons (or people who are not specially oppressed but have appointed themselves as spokespersons) voice an accusation against another individual or individuals. As Loretta Ross describes,

Call-outs are justified to challenge provocateurs who deliberately hurt others, or for powerful people beyond our reach. Effectively criticizing such people is an important tactic for achieving justice. But most public shaming is horizontal and done by those who believe they have greater integrity or more sophisticated analyses. They become the self-appointed guardians of political purity. [Emphasis added.]

Those who have been accused then have two choices: either to apologize or attempt to defend themselves. If they choose to defend themselves, they are labeled “defensive,” merely compounding their transgressions in the eyes of the rest of the group.

The notion of “due process,” or the right to defend oneself, is disparaged within callout culture—deemed a “bureaucratic” obstacle standing in the way of “justice.” Those seeking “justice” rely on their own moral outrage to prove their commitment to fighting oppression—which is judged interpersonally rather than by any part they have played in struggling to combat the oppression produced by the system.

In some ways, it is understandable that callout culture has replaced due process in the eyes of many young radicals—simply because, whatever its claims to the contrary, the U.S. court system perpetuates injustice. Women who accuse men of raping them are often interrogated as if they are to blame for their assaults, by dressing in certain ways or giving nonverbal approval even if clearly they say “no” to sex. People of color are routinely jailed and/or brutalized for crimes they did not commit. Black people are routinely murdered by police simply for being Black.

Of course, the entire left must believe survivors, who have overwhelmingly been ignored and/or vilified in capitalist society.

But the corruption of the legal system does not eradicate the importance of due process—including on the radical left—because assuming guilt when an individual accusation is made is as undemocratic as assuming innocence. If we automatically assumed guilt or innocence, there would be no need for a grievance process. In each case, both the accuser and the accused must be given the opportunity to submit evidence on their own behalf. This has historically been common sense on the left, as is immediately apparent from the DSA’s current grievance process.

Over many years the ISO’s leadership fought hard to prevent callout culture from overtaking the ISO—engaging in sharp argument when necessary. We did so because we had seen organizations much larger and stronger than the ISO destroyed by the circular firing squad of identity politics. When members of the SC Majority chose to embrace this interpersonal approach to combating oppression, claiming that the ISO’s internal culture was “undemocratic” and “racist,” they set the ISO on a collision course that took on a life of its own, which would inevitably lead to the destruction of the ISO.

“Anarcho-liberalism” (radical in form; liberal in substance) has been a key influence on activists in the U.S. since even before the Occupy movement of 2011, and callout culture has been one of its components. One of its other components is a preference for horizontal organizational structures rather than elected leadership bodies. The standard norms of democracy are an anathema to horizontalists. Alongside this preference for anarchist-based structures, however, most anarcho-liberals continue to support and vote for Democrats when election time comes.

At the February convention, the ISO adapted to the politics of anarcho-liberalism without acknowledging doing so: First, by adopting callout culture; second, by electing members to the SC who support the strategy of campaigning for socialists running in the Democratic Party—including Bernie Sanders in 2020; third, by decentralizing organizational authority into self-selected and autonomous “working groups” while denigrating the need for a national leadership united around key principles. The convention did not hold an open debate about changing our long-standing organizational norms but rather established “facts on the ground” that effectively undermined the established organizational practices of the ISO.

Was the ISO racist?

Since its inception as a tiny organization, the ISO has a proud history of fighting against racism, including our long-standing participation in the Campaign to End the Death Penalty, initiating the Midwest Network to Stop the Klan, organizing against police killings in our localities, building the Black Lives Matter movement, building immigrants’ rights organizations, organizing against Islamophobia, combatting fascists, and much more. But none of that mattered once the focus turned inward, and categorical judgments were made on the basis of alleged interpersonal behaviors rather than the commitment to campaign and struggle against the roots of racism as a lifelong project.

Nevertheless, for example, accusations of “Islamophobia” were unleashed against some comrades from the SC Minority at the February convention—merely because of political arguments they had made years earlier during debates over the character of the Charlie Hebdo attacks—which denounced the strategy of terrorism while also condemning the main enemy as imperialism. How is this “Islamophobia”? (Perhaps ironically, members of the SC Majority, including Socialist Worker editor Alan M., took the same position as we did at the time.) Another accusation of “racism,” stemmed from a debate centered only in New York City in 2010 and again in 2013, which were both withheld from the rest of the organization, including its leadership. How is the national leadership then held culpable in the outcome of this New York City-centered debate?

To be clear: We have no doubt that the complaints by individual comrades of color at the February convention about their treatment in the ISO are true, and socialist organizations should aim for much higher standards than capitalist society as a whole in combating all internal vestiges of oppression. But intention also matters. Those who are committed to fighting against racism and all other forms of oppression are clearly not enemies in the same mold as political reactionaries or those who actually run the capitalist system and sustain the forms of oppression that maintain it. One of the central tenets of Marxism is the need to overthrow the capitalist system in order to create the material conditions that can even begin to uproot racism and other forms of oppression in society at large.

But that requires a foundation of solidarity among all those who are exploited and oppressed, who all have an interest in working-class power. All of us are damaged by capitalism, and we are all a far cry from the people who will live in the society that we hope to create. Unfortunately, callout culture, intentionally or not, centers everything that divides us from each other to the detriment of building movements that are as broad and influential as possible.

At the ISO convention and afterward, some comrades of color accused other comrades of color of perpetuating racism in the ISO. Surely, we must do better than that if our aim is truly to build a multiracial organization.

Loretta Ross’ words are especially insightful in this context:

These types of experiences cause me to wonder whether today’s call-out culture unifies or splinters social justice work, because it’s not advancing us, either with allies or opponents. Similarly problematic is the “cancel culture,” where people attempt to expunge anyone with whom they do not perfectly agree, rather than remain focused on those who profit from discrimination and injustice…

Call-outs make people fearful of being targeted. People avoid meaningful conversations when hypervigilant perfectionists point out apparent mistakes, feeding the cannibalistic maw of the cancel culture. Shaming people for when they “woke up” presupposes rigid political standards for acceptable discourse and enlists others to pile on. Sometimes it’s just ruthless hazing. [Emphasis added.]

Rape coverup in 2013?

The ISO has fought against sexism from its beginning—including organizing the defense of abortion clinics and activist opposition to all forms of sexual assault and domestic violence. But none of this made a difference when an anonymous former member (“FM”) issued a statement accusing the 2013 SC of covering up a rape in the ISO, singling me out as the main perpetrator (the “Supervisor”) and another SC member as the “representative”). FM’s statement fails to even mention that a different SC member, a comrade of color, was on the Appeals Committee that actually made the decision to take no disciplinary action in the 2013 case. Nevertheless, FM’s accusation (widely distributed on the internet) has been treated as a statement of fact. It is not. Rather, it is an act of slander.

I have never, and could never, cover up a rape. There are two sides to this story—and I was denied the right to tell my side by the newly—elected SC. A close comrade shared the early, unredacted version of the letter by the Former Member (who signed the letter with their personal initials at that time). As soon as I received it, I contacted Todd C and Jen R, from the SC Majority and the newly elected SC writing, “I have just finished reading [FM’s] letter. It contains many glaring omissions and inaccuracies.” I requested that the SC circulate, with FM’s accusations, a letter of complaint received by the SC in 2013 from a group of witnesses stating that the National Disciplinary Committee (NDC) had violated numerous disciplinary procedures—which the SC had been required to investigate at the time. In the process of that investigation, we discovered the other violations of due process by the NDC—which required the SC to intervene. This was the only motivation for our/my intervention into the disciplinary process in 2013.

A member of the 2013 Appeals Committee that ultimately decided the case also wrote to Jen R. and Todd C. upon receiving FM’s statement, asking them to contact her because she had pertinent information on the case. They never gave her the courtesy of a reply.

I wrote to Jen R. and Todd C. a second time to say, “In addition, [FM’s] letter is about much more than alleged mistreatment by [XX] and me. I documented some of the omissions and inaccuracies in my earlier email to you. I believe that it would be irresponsible to simply circulate FM’s document without comment–thereby implying that everything in it is true.” Instead, the newly-elected leadership shared the document far and wide, with the SC’s endorsement of its accuracy and without allowing me or anyone else the opportunity to refute the charges.

Without allowing any rebuttal, FM’s slanderous charges, many based on FM’s wild imagination and asserted without evidence, were accepted as fact by most of those who read it. One such charge is, “Throughout the history of the organization, The Supervisor [the name FM assigned to me] had been handling the organization’s sexual assault cases. The Supervisor did this largely based on their own behavioral assessment of individuals. If The Supervisor thought you were a decent person and you insisted that you were innocent, then The Supervisor believed you. If you left the ISO, or said you were innocent but abandoned the process, then your behavior was suspect and The Supervisor believed the victim. Minimizing chaos in the branches seemed highest on the (sic) The Supervisor’s priority list.”

Besides the fact that FM offers zero evidence for these claims, they erase my life-long commitment to women’s liberation on every level. A year ago, I (along with Todd C on behalf of the SC) expelled a member who resigned from the SC when a serial rapist was named by survivors in an ISO branch. We expelled that former SC member for using his leadership status to maintain an abusive and grossly sexist climate in the branch. Does anyone wonder how I could both alledgedly cover up a rape and expel a member of the SC for abuse? I am the same person now that I was in 2013 and 2018, with the same principles that guide my life.

It is astonishing to me that comrades who have known me (and other members of the 2013 SC) for decades chose to believe the account of an anonymous ex-member when I/we were never given the opportunity to respond. I also received a flow of hate mail (including a physical threat) by numerous ISO members since the letter was sent to the membership by the SC. But callout culture holds the right of due process in contempt, preferring universal condemnation on the basis of an accusation rather than letting actual facts stand in the way.

To be clear: I have never disparaged any member of the NDC who heard the 2013 case and will never do so. Just a few weeks after our 2013 convention elected an independent National Disciplinary Committee (NDC) we were all faced with the first rape accusation it would be required to investigate. None of us was prepared—especially after the British SWP scandal that involved a possible cover-up of a rape by the SWP national organizer against someone who worked for their organization. Before the rape accusation against an ISO member emerged, we thought that we would have a few months to think through many aspects of the new NDC and its mission. Instead, we were forced to scramble for a set of disciplinary guidelines.

We did the best we could under the pressing circumstances we faced. We also understood that the SC was responsible for developing a disciplinary process that would set precedents for all future sexual assault cases. Would we have done things differently in 2019 than we did in 2013? Absolutely! We were inexperienced back then, and adapted our disciplinary process as comrades on the disciplinary committee gained experience. But for what it’s worth, although comrades adapted aspects of the initial disciplinary procedures as they gained more experience, especially with sexual assault cases, most of these procedures—including the insistence on due process—remained intact until the ISO dissolved itself in 2019.

The two key political issues at stake in 2013: Due process and confidentiality

Maintaining the integrity of a disciplinary process on sexual assault cases requires 1) the right to due process, and 2) confidentiality.

It does not surprise me that the 2013 NDC “corroborated” FM’s version of the conflicts that took place during their deliberations on that case. We had political disagreements that are lost in FM’s account, which I will outline below. To be clear, tempers flared on both sides of the conflict, not just mine, so the idea that I alone was a “bully” is outlandish.

1. The right to due process as key to democracy. One of the 2013 SC’s “crimes” according to FM’s narrative, was defending the right to due process. FM treats the right to due process as a key element of the alleged “coverup”: “The SC’s misguided obsession with legalistic due process contributed to [the accused’s] exoneration.” So now we are to believe that the entire 2013 SC wanted to cover up a rape and used the right to due process as an excuse to do so? In addition, the accused was not “exonerated” as FM claims; the independent Appeals Committee only found that there was insufficient evidence to discipline the accused—specifically because the accuser refused to participate in the disciplinary process. The details appear below.

To be clear, I did instruct the Appeals Committee (after the NDC debacle) “The statements constitute evidence in and of themselves, but cannot BY THEMSELVES constitute sufficient evidence for a finding.” This directive, however, was for this case only, because the accuser refused to participate in the disciplinary procedure in this specific case—that is, refusing to communicate with anyone on the NDC or the Appeals Committee, even through their chosen representative, during their investigations. If they had not refused to do so, this cautionary statement would have been unnecessary. So, these recommendations were not meant for all disciplinary cases moving forward. Again, we did everything possible to convince the accuser—even through their chosen representative—to participate in the process, but we were not successful.

Due process is foundational to any genuine democracy and is a crucial component of what separates our tradition from Stalinism, which vilified and punished Trotsky and his supporters in the 1920s and 1930s and has continued to use this undemocratic method ever since. I did not take a position for or against the accused member in 2013 (and never had access to the witness evidence collected either by the NDC or the Appeals Committee). I only sought to defend the right to due process–which since then became well established in our disciplinary procedures. I am proud of that fact, and do not agree that I did anything wrong in defending the right to due process for both parties in our disciplinary procedures.

And for the record, I had no access to the specific evidence procured by either the NDC or the Appeals Committee, which eventually decided the case. In addition, I did not “promote” the accused member toward leadership positions in the ISO because I remained doubtful of his integrity as he was elected to leadership positions in the New York City district in recent years. In this, as in other respects, FM’s claims are false.

In reality, due process has proven to be crucial in defending the integrity of our disciplinary procedures. After Todd C and I expelled the former SC member on behalf of the SC last year, that ex-member filed an appeal objecting to their expulsion. The Appeals Committee rightfully examined in detail whether we had followed the disciplinary guidelines and offered due process to the former SC member who was expelled. Because we had followed the disciplinary guidelines, the expulsion was upheld by the Appeals Committee.

In the context of their embrace of callout culture, described above, it is not surprising that the newly-elected ISO leadership denied the right to due process to me and other former SC members who were targeted for suspension, based on a single statement issued by Alan M, who was also on the 2013 SC. Alan’s “recollection” of the 2013 case singled me and two other SC members out for having been “more responsible” than others from the SC at the time (including, not surprisingly, Alan M!). Alan’s statement (without evidence) resulted in our immediate suspension from membership.

But our suspension letter did not even tell us what the charges were, while informing us that our membership status would be determined by an upcoming “investigation.” Not only were we denied the right to defend ourselves, but we were not even informed what charges we faced.

Before any “investigation” could take place, the suspended SC members were condemned with the speed and ferocity of an angry mob in a house-to-house search. This strikes me as a continuation of the purge that took place at the 2019 ISO convention.

2. Confidentiality. FM’s detailed public exposure about the 2013 case (especially its earlier, unredacted version), which has circulated widely on the Internet, contains identifying information that could easily re-traumatize the accuser—who explicitly and emphatically requested anonymity, and which we promised to them. I never learned or asked for the complainant’s name, out of respect for their request.

I have continued to honor the accuser’s request for anonymity since FM’s statement appeared in March—even though I have all the emails and other information that could clear my name. I could not in good conscience contribute to the violation of confidentiality that has already taken place.

Far too much information and disinformation now floating around the internet compromises the ISO’s commitment to confidentiality in this and all sexual assault cases. If an accuser wishes to make their case public, that is their choice. But many accusers request confidentiality, and their requests should be respected. If the ISO could not guarantee confidentiality, others would be discouraged from filing a complaint in the first place. It is also the case that the complainant can go elsewhere to seek justice if they choose.

FM, however, has no respect for the complainant’s request for either anonymity or confidentiality, freely admitting, “Though the other investigator and I were not supposed to learn who the Complainant was, towards the end of the case we had to figure it out in order to confirm some details of her testimony.” In so doing, the investigators violated the complainant’s request for anonymity during the investigation, and FM has done so again, by circulating this information publicly with personally identifying information.

FM refers to confidentiality as “secrecy,” as if it were imposed by the SC, alleging, “But the membership never knew about the case. All information was quashed; in part, because the SC was embarrassed, in part, to protect the accused’s reputation and to appease the district where his friends resided.” Once again, FM engages in slander while disrespecting the complainant’s explicit request for anonymity.

For those who agree with FM that respecting the right to confidentiality amounts to “secrecy” and deception, it is worth reading a recent memo issued by the DSA’s leadership on the importance of maintaining confidentiality in disciplinary cases, which appears below—demonstrating that confidentiality was not some manipulative quirk of the ISO, but an essential component of due process:

The Resolution 33 process was initiated at the 2017 DSA convention. The Resolution 33 process is intended to be confidential. To avoid conflicts of interest and to make the consideration of all grievance appeals as fair and impartial as we can make it, the NPC adopted procedures including delegating authority to the NPC Steering Committee to address grievance/appeal matters under Resolution 33.

… Then a summary report will be generated with a recommendation for adjudication by the NPC. The reports will not identify either the individuals involved or their chapter. While NPC members may have independent knowledge of the behavior and/or conflict at the heart of an individual grievance appeal, are expected to review the reports and recommendations fairly and impartially. The facts will be kept confidential as will the recommendations. [Emphasis added.]

Then vs. now

Back in 2013, the NDC, not the SC, declared a mistrial in the case, stating,

On June 15, 2013, the disciplinary committee finds that this hearing has ended in a procedural mistrial. After coming to a unanimous decision, we now rescind our votes, our verdict, and our recommendations on account of these very serious procedural errors . . . A hearing simply never took place.

According to the guidelines distributed to the Disciplinary Committee, the Respondent and presumably the witness, a hearing was supposed to be convened after our initial investigation. The Respondent was supposed to have been given the right to call witness in front of the Panel to address the entire Panel and to rebut charges and allegations of witnesses to the Panel.

No hearing was ever convened. The Respondent (a) never had the opportunity to address the Committee, and attempt to convince them of his innocence and; (b) the Respondent never had the opportunity to rebut witness testimony.

—The 2013 Disciplinary Committee

In addition, although FM now claims, “I don’t know the rest of the story. I left the organization in disgust” after the NDC case, they stuck around long enough to publish a document on the ISO’s disciplinary procedures for the 2014 convention, the following year. That document read, in part:

The Steering Committee and the Rules commission have worked very hard to develop a reasonable, effective, just, and democratic disciplinary process. I think we should be proud of what our organization is trying to accomplish. But I also think we need to recognize the significant organizational, social, and political challenges created by the process we set into motion at the 2013 Convention. I wish I could offer solutions and resolutions, but right now all I can offer is the best assessment I’m capable of giving. I hope these comments will contribute to a constructive and productive discussion.

[FM], PCB #13 ISO Convention 2014

There is zero evidence that anyone coerced FM to submit that document.

End of an era

I have shared here some of the most relevant information that I hope sheds light on the politics behind the ISO’s collapse. It is never good news for the left when socialist organizations dissolve—whatever political disagreements others may have about specific aspects of their politics. Just as the exponential rise of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) in recent years has benefited the entire U.S. socialist movement—representing a stronger and forward moving left—the demise of the ISO as part of its revolutionary socialist component narrows the left’s political capacity as a whole.

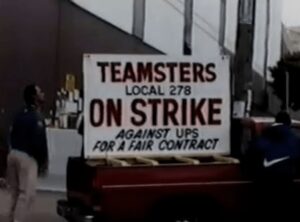

It is nothing short of tragic that the ISO, an organization based on the self-emancipation of the working class, imploded just as the class struggle began to revive in the U.S. over the last year. The ISO was founded in 1977, precisely at the time that the U.S. ruling class launched its neoliberal project in the form of a frontal assault on the working class and the oppressed. The class struggle entered a downward spiral that lasted for the following 40 years and receded into a distant memory for those of us old enough to remember it and unknown to younger generations of ISO members.

Most of us had high hopes that the return of class struggle would impact the ISO in a positive way. It is too late for that, and much is yet to be written that can place the ISO’s destruction in an international context, as part of the larger crisis for the revolutionary left.

But the question remains: Couldn’t those who wished to join the DSA have simply done so without destroying the ISO? Hopefully, when the history of the ISO is written and cooler heads prevail, the architects of this disaster will be held accountable for their own role in destroying one of the largest and most viable revolutionary socialist organizations in the heart of US imperialism. That accounting should include their contempt toward those who dedicated our entire adult lives to building the revolutionary socialist movement and now find our lives ruined—ironically, in the name of “justice.”

Sharon Smith is the author of Subterranean Fire: A History of Working-Class Radicalism in the United States (Haymarket, 2006) and Women and Socialism: Class, Race, and Capital (revised and updated, Haymarket, 2015).