On May 7, the Chilean right scored a major victory in elections to choose delegates to draft a new constitution for the country. The conservatives, who mostly want to maintain the current constitution drawn up under the Pinochet dictatorship, have more than the 60 percent support in the constitutional council they need to write the new constitution without having to offer any concessions to the left. They will start with a draft prepared by a 24-member congressionally appointed Council of Experts that also holds an overwhelming right-wing majority.

These developments marked a sharp reversal from the period of mobilization and struggle that opened in November 2019, when mass demonstrations took to the street in protest of the right-wing government of Sebastian Piñera. That period led to the election of a left-dominated constitutional convention. But Chilean voters overwhelmingly rejected its draft constitution last September. The new constitution will have to be voted on by December 2023.

This article provides essential analysis to understand these whiplash-producing developments. It appeared originally in rebelión.org and was republished in Correspondencia de Prensa. The ISP translated it to English.

The recent elections of delegates to the constitution-writing convention should be analyzed in the context of the political process inaugurated in November 2019, when the different parts of the political elite approved the Agreement for Peace and the New Constitution, to contain the popular anti-capitalist protests that threatened not only the stability of the Piñera government, but also the whole system of domination in Chile.

Indeed, this agreement, supported by the Frente Amplio (FA) to the Unión Demócrata Independiente (UDI), ceded the strategic initiative to the ruling classes and managed to redirect the popular impulse for change towards the institutional sphere. All this was in a context of profound weakness of the revolutionary social and political organizations. A weakness that, at this point, is endemic. In this sense, the defeat of reformism in the constitutional plebiscite of September 2022, showed both the political weakness of the “progressive” sectors that pushed for a change in the Constitution, as well as the programmatic shortcomings in the text that was put to the vote. The “culturalist” emphasis of the defeated text and the renunciation of deep changes in the model of class domination alienated important popular sectors.

Overcome by the electoral defeat of September and by its own incapacities in the management of the government, reformism, systematically pressured by the media at the service of the bourgeoisie, once again gave in. Thus, in March 2023, after a broad political agreement, the government announced the creation of the Commission of Experts whose members, nominated by the National Congress, came from the ranks of the different parties of the system. The experts were nothing more than the voice of the different fractions of the bourgeoisie. This Commission of Experts is drafting, behind the backs of the people, a constitutional text that will not substantially modify the economic model or the political regime.

On the other hand, the media-driven emphasis on crime—especially those involving immigrants— refocused public discussion on the security situation. Problems associated with health, education, pensions, housing, and salaries disappeared from the agenda. In fact, very few learned, in July 2022, that that the median wage in Chile remained stagnant at 457,690 pesos, according to the government’s statistical agency. Thus, with the popular forces vacating the streets, with a fragmented revolutionary left that lacked the capacity to influence the political situation, with the reformists hemmed in by their neoliberal allies and with an increasingly vociferous and aggressive right wing, the election of constitutional councilors on Sunday, May 7 took place.

In this new election, 12,858,472 people voted, which represents 85% of the total number of voters (15,150,571), a slightly lower percentage than the 85.7% that participated in the plebiscite of September 2022. The obligatory nature of the vote and the reiteration of the threat of fines for those who did not vote undoubtedly had an important impact on the massive turnout for the “celebration of democracy”.

The distribution of participation was random. In the high-income municipalities of the Santiago Metropolitan Region, such as Las Condes (76.4 percent), Vitacura (77.89 percent) and Lo Barnechea (83.09 percent), participation remained high, although lower than the national average. Meanwhile, in the working-class areas, which regularly have low participation rates, turnout was particularly high this time: La Pintana (86.77 percent), Pudahuel (88.43 percent) and Puente Alto (89.08 percent).

On the other hand, the null vote and the blank vote also increased significantly. The null vote reached 16.98 percent, while the blank vote reached 4.55 percent. Between the two, the total reached 21.53 percent. Thus, considering abstentions, null votes, and blank votes, we reached a total of 4,980,077 people who did not express any interest in the event or in the candidates. That is to say, 32.87 percent of the voters remained indifferent to the process.

But some clarifications are in order. Many of those who did not vote on this occasion did so out of indifference to the political process, and although this manifestation is a form of political rejection, it wasn’t the result of an active and organic boycott campaign, but rather a reflection of a disregard for politics. On the other hand, it is important to point out that many of the people who abstained from voting went to police stations to justify their failure to vote. We are not in the presence, as some believe, of an attitude of rebellion against the ruling class, but rather, in the presence of a growing political apathy.

However, the results of the election of delegates to the constitution-writing convention show results that go beyond the electoral situation. On the one hand, the extinction of two “centrist” parties, Christian Democracy (DC, 3.78 percent) and the Radical Party (PR, 1.58 percent), is evident. These are two veteran parties that in the last two decades have seen their electoral “niches” fade away.

Conservatives turned from the DC to the UDI and more recently to the Republicans, while the growing secularization of society has found different political expressions, ranging from the Party for Democracy (PPD) to the FA.

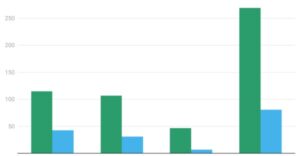

It is also interesting to note the decline of the parties that make up the Chile Vamos (broad right-wing) coalition, a phenomenon that began with the election of the Constituent Assembly members in May 2021 and then extended to the first round of the presidential election in November of the same year. Indeed, the Chile Vamos coalition, which on this occasion presented itself under the slogan Chile Seguro, obtained only 21.07 percent of the vote, and parties that until recently were hegemonic in Chilean politics, such as the UDI, obtained only 8.86 percent of the electorate. It is evident that the political organizations that formed the Concertación, the neoliberal “center left” governments that dominated Chilean politics for decades after the end of the Pinochet dictatorship, have experienced a deep attrition. So has the mainstream right, as was seen in the last presidential term of Sebastián Piñera (2018-2022).

Everything indicates that Republicans, with 35.4 percent of the vote, has become the new home of the dictatorial right. Indeed, this party, with a discourse that vindicates the preservation of the Pinochet Political Constitution of 1980, the application of harsher punitive measures against the criminal world and against popular protest and that proposes greater repressive zeal against migrants, has managed to project not only the expectations of the economic and social elites, but even that of broad sectors of ordinary people. In fact, Republicans obtained the first electoral majority in 12 of the 16 regions of the country. Furthermore, in 9 of these 12 regions, Republicans obtained a vote higher than its own national average (35.4 percent), making the regions of Tarapacá (41.19 percent) and Bio Bío (43.34 percent) its new bastions.

But we must not be confused. The Republican Party is neither a more extreme right wing nor a fascist right wing (in the historical sense of the concept). It is a right wing at the service of the bourgeoisie, just as other groupings in the same vein have been historically, and as are their peers in Chile Vamos. Indeed, the right wing in Chile has been historically conservative and authoritarian. It was so in the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, with conservatives and liberals; it was so in the 20th century with Alessandrismo and Ibañismo, and even pressured the reformist governments of the Popular Front and Eduardo Frei Montalva towards authoritarianism.

One expression of this was the successive, and widely documented, massacres of workers throughout the last century. This same right wing was the one that unconditionally supported the repressive policy of the dictatorship and, with the Concertación de Partidos por la Democracia, it was the one that implemented a policy of impunity for the repressors. There has never existed in Chile a democratic or liberal right wing and the differences between Republicans and Chile Vamos are reduced to how harsh and widespread is the repression they advocate. There is no “worse” right wing to be contained, it is the right wing as a whole, the fundamental support of the bourgeoisie, that must be defeated.

The scenario that is taking shape has the Right (with 39 of 50 constitutional councilors), as administrator of the institutional destiny of the country. That is to say: those who were resoundingly opposed to the constitutional change until October 2019, are today those who have control of the constitutional process. This even allows them to be generous with the defeated and grant them some minor demands in terms of civil and cultural rights. The objective will be to add them to the construction of the “house of all” and, in this way, to give the constitutional text the political legitimacy it should have in the exit plebiscite (December 2023). It is not unusual, following the reasoning of President Gabriel Boric on the evening of May 7, that the new constitutional charter will implement increasingly strict police powers in matters of public order and migration and that it considers a broad framework of operations for capital investments, local and foreign. In exchange, it may grant progressivism some crumbs in matters of interculturality and gender equity. In short, nothing that threatens the accumulation of capital of the bourgeoisie and, consequently, its capacity to control and repress popular protest.

Goicovic Donoso

Igor Goicovic Donoso is a contributing writer for Rebelión.