Last month marked the first 100 days of the far-right administration of President Javier Milei in Argentina. Pablo Stefanoni analyzes developments in an article republished in Correspondencia de Prensa. The ISP translated it to English.

Last December 10, on the 40th anniversary of the recovery of Argentina’s democracy from military dictatorship, the economist Javier Milei, an “anarcho-capitalist” who has expressed skepticism about democracy and who continues to consider the State a “criminal organization,” took power.

Milei strives to show that his taking power not only doesn’t make him more moderate, as expected, but motivates him to be even more radical in tearing down the system. He sees himself as a character in a sort of Atlas Shrugged on the Rio de la Plata with all of the images of an heroic capitalism from Ayn Rand’s 1957 novel, paired with messianic visions of politics of himself as the biblical Moses; or to compare his sister Karina [one of his closest aides] with Moses and to reserve for himself the role of Moses’ brother and “translator”, Aaron.

The troll president

For Milei, the national reboot means putting an end to “100 years of collectivism” that would have derailed the country from the path 19th century liberals set for it, leading it to become a huge ‘villa miseria’ (shanty town). He also wants to put an end to the political “caste.” He even revived the slogan “Que se vayan todos” (Out with them all!—a slogan similar in U.S. parlance to “Throw the bums out!”) that rang through the streets during the Argentinazo, the 2001 social rebellion. Despite this, his government is filled with career politicians, including former Peronist presidential candidate Daniel Scioli, who lost to conservative former president Mauricio Macri, in 2015. Scioli is now Secretary of Tourism, Environment and Sports.

The economic deterioration of the last years——with inflation running at more than 100 percent and with the portion of the population in poverty increasing to more than 40 percent——led voters from the middle and lower sectors to trust his appeals and to choose La Libertad Avanza, Milei’s electoral label, with a mixture of weariness for the known and hope for the unknown. At the same time, it is difficult to explain the Argentine electoral result without considering the global climate, with the rise of new radical right-wingers and supposedly “anti-establishment” politicians.

Milei delivered his inaugural address to his supporters outside of the national parliament rather than speaking in the legislative chamber, as was traditional. This action symbolized his “fight against the caste.” His recent address to the nation showed his contempt for a Congress in which his party is in a minority and depends on the right-wing Republican Proposal (Pro), Mauricio Macri’s party, and on sectors of the opposition that is willing to work with him, despite his penchant for insulting them.

“There is no room for squishes (tibios)”, said the president of the Chamber of Deputies, Martín Menem, a member of Milei’s party and one of the relatives of the neoliberal ex-president Carlos Menem (1989-1999) who are part of the new ruling party.

Milei’s fury increased in March when a majority in the Senate rejected his December emergency decree (known by its initials DNU) repealing or modifying some 300 laws in an effort to deregulate the economy. For now, however, this decision has no legal effect if the Chamber of Deputies does not also vote to reject it.

The president reposted a message on social media listing the senators who voted against the DNU alongside the letters HDRMP (similar to the English “SOB”). He had also threatened to “piss” on the provincial governors after his “omnibus bill”—with more than 500 articles and granting special powers to the president—failed in the lower house. He has called Congress as a “rat’s nest”.

Addicted to social media, Milei acts like a true president-troll, in the mold of Donald Trump. Armies of followers—both organized and spontaneous—support him with violent online attacks, using enflamed rhetoric and memes to discredit the opposition.

These include “they don’t see it” (opponents don’t see reality), “lefty tears” (leftists crying over the loss of their privileges) or “the forces of heaven” (on which the government stands), along with a variety of other memes in which Milei is presented as a roaring lion or a superhero.

Milei, reaching further for his mystical side, repeats a quote from the Book of Maccabees pointing out that, in battle, victory does not depend on the number of soldiers, but on the forces of heaven. Close to the Hasidic organization Chabad Lubavitch——even though he is not Jewish——he often tweets biblical messages in Hebrew to reaffirm that he is not leading an ordinary government. On the contrary, he’s leading a revolution that goes beyond earthly limits.

Culture war

Since his leap into politics in 2021, after gaining notoriety as an eccentric TV panelist obsessed with John Maynard Keynes——a name that literally drives him crazy——Milei began to adopt the language of the “alt right”. He first denounced the alleged omnipresence of the São Paulo Forum——a weakened network of left-wing parties in Latin America—— for plotting coups. He ended up becoming a crusader against “cultural Marxism”.

In that mindset, he denounces global warming as a socialist invention and links “radical feminism” and environmentalism with a plan to reduce the planetary population through abortion and degrowth.

Milei presents his policies as true revenge against progressives. The closures of the National Institute against Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racism and of the state news agency Télam, and the cuts in funding for Argentine cinema and the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research are celebrated as victories against cultural Marxism that bring on “lefty tears”.

Libertarian activists even celebrate worker layoffs, often at the gates of the “cancelled” institutions. “Cruelty is in fashion,” said writer Martin Kohan. A cruelty mixed with the norm-breaking characteristic of social networks and the new right.

The “anti-picketing” protocol criminalizing street blockades, adopted by the Minister of Security, Patricia Bullrich (who ran for president herself in 2023 and didn’t make it to the runoff) is similar. “Hawk” of the traditional right wing, who already occupied the same position in Macri’s (2015-2019) government, Bullrich is a key member of the government. She has made of the mano duro (law-and-order) against crime and social protest, her calling card. If the anarcho-capitalist Milei spoke critically of the “repressive forces of the State”, President Milei is “all in” on his minister’s threats of repression.

Milei’s latest provocation was to mark March 8——while tens of thousands of women were marching in Buenos Aires for International Women’s Day——by replacing the Hall of Argentine Women in the Casa Rosada (the seat of federal government) with the Hall of Heroes (Próceres). The previous hall, which included women of different biographies and ideologies, was thus changed for portraits of heroes, all male, including the traditional “founding fathers” with figures such as the controversial former President Menem, who imposed a radical privatization program in the 1990s. For Milei, Menem is just another hero.

The person in charge of this change was Karina Milei, the president’s sister, whom he calls “the Boss” and current secretary general of the presidency. The renowned historian Roy Hora characterized the change as upholding “an archaic and exclusive idea of a nation… with the smell of mothballs”.

Criticized for his misogyny, Milei responds by holding up the women in his cabinet: Bullrich, Chancellor Diana Mondino, and Minister Sandra Pettovello, at the head of the Ministry of “Human Capital” that absorbed the portfolios of education, labor, social policies, women and human rights, along with Karina.

Vice President Victoria Villarruel, a lawyer who has a long record of advocating for the military officers convicted for crimes against humanity committed during the last dictatorship (1976-1983), but whose style and interests permanently clash with Milei and his entourage, can also be added to the list.

This “culture war” places Milei in the global tribe of the political ultras. He believes that the West is in danger because it has abandoned the ideas of freedom, as he pointed out before the World Economic Forum in Davos, which he considers a club of socialists.

Having, in 2013, become a follower of the most radical version of the “Austrian school” of free-market economics——that of Murray Rothbard——the Argentine president has become an icon of the libertarian right. But his anti-progressivism (“anti-wokeism”) also connects him with the most reactionary sectors. As such, he was one of the guests at the last Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in the U.S., where he couldn’t hide his excitement at meeting Donald Trump. Milei also visited the far-right Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni——in the same trip in which he tried to reconcile with Pope Francis, whom he had called “representative of the devil on Earth”——and maintains close ties with the Bolsonaro family in Brazil. He also received numerous accolades from Elon Musk, with whom he shares a visceral hatred for social justice.

Chainsaw and blender

During his campaign, Milei brandished a chainsaw to symbolize his plans to cut public spending, that, he promised, would only affect the “caste”.

But his shock program reached such an extent that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) itself warned him not to neglect working families and the most vulnerable, for fear of a social explosion. In January, poverty already affected more than 57 percent of the population, according to the Observatory of the Argentine Social Debt of the Catholic University.

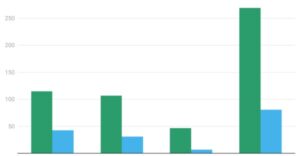

More than the chainsaw, Milei has used a blender (to liquidate spending): he froze government spending at 2023 levels while inflation increased 20.6 percent in January and 13.2 percent in February (a figure the government celebrated for its alleged downward trend).

Pensions’ purchasing power dropped 30 percent. The reduction of social benefits, stoppages on public works, cuts in revenue sharing with the provinces and postponement of debt payments explain the financial surplus that the government is celebrating. Economists view this with skepticism, especially in terms of its sustainability.

Tensions between the federal and provincial governments marked these 100 days because of the federal administration’s refusal to transfer funds. But in the case of the province of Buenos Aires, the most populous and governed by Peronist Axel Kicillof, Milei supported the call for a “fiscal rebellion”——in essence, refusing to pay taxes——launched by Congressman José Luis Espert, an ally of the government.

But Milei’s strategy of financially strangling the provinces to enforce austerity as radical as the federal state has a double edge, and it is enough to recall the violent provincial social outbursts in the 1990s.

“Let’s go Toto [Luis Caputo, Minister of Economy]. Deficit 0 is not negotiable”, wrote Milei on X/Twitter. For his part, Caputo asserted that “there is no world precedent of a five-point deficit reduction in a month, and what this shows is the President’s commitment”.

Although Milei considers that all taxes are theft and that evading them should be a human right, he intends to increase several of them, and he even extended the misnamed income tax (salary income) that the former Minister of Economy and presidential candidate Sergio Massa had reduced last year, during the electoral campaign.

The economy will be the key

The cultural battle serves to unite and entertain Milei’s base, but the president won the election because he convinced 30 percent of the electorate in the first round and 55 percent in the second round that his recipe would rescue the country from the crisis and move it towards a promising future of freedom and abundance. And it will be on that terrain where his future will be defined——and his capacity to build a political-social support bloc that he lacks today.

The government is stable for moment because the Justicialist Party (Peronist) opposition is still reeling from its electoral defeat and the strong social rejection of the dominant Peronist sector in the last 20 years, that of former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. The political system has been unable to decode “mileísmo.” And the moderate opposition fears that Milei may turn to his populist demagogy to capitalize on the legislative rejection of his measures in the parliamentary elections of 2025.

In the meantime, everyone wonders how long popular approval——which according to surveys seems to be holding up——for the most unclassifiable and extravagant president in the last four decades of Argentine democracy will last.