This post was first published on May Day in the Lebanon journal, Project Zero, in Arabic.

May Day is traditionally celebrated as International Workers Day when people mobilise to support the strength and importance of labour in its perennial struggle against capital in society. Apart from participating in marches and demonstrations around the world, it is also an opportunity for us to consider how well the organisations of the working-class are faring in the 21st century.

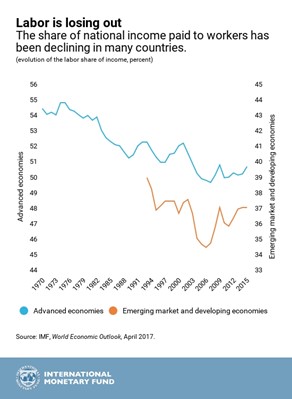

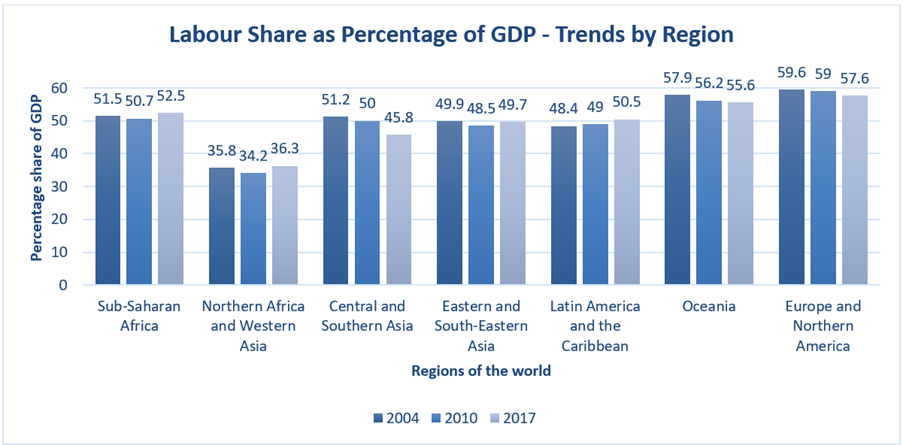

First, the bad news. From the 1980s, when the policies of neoliberalism were imposed by governments in all the major economies and often followed in the rest of the world, labour’s share of national income in most countries fell.

This was the result of several factors. In the 1960s and 1970s, the profitability of capital globally fell sharply. Capital could no longer afford to make concessions on wages, social benefits and public services. Now the order of the day was privatization, the weakening of trade unions and labour rights, cuts in taxes on the rich and the reduction of employment by transferring industry to the cheaper labour parts of the world.

There was increased exploitation of workers at work. And any increase in the productivity of labour through more intensity of work, the deregulation of workers’ rights and more automation went mostly into profits for the owners of enterprises. The fall in labour’s share was also powered by a series of slumps in capitalist production that weakened workers’ power in negotiations for wages and employment. Firms in the rich economies of North America, Europe and Japan shipped their manufacturing operations to the poor ‘Global South’ to increase profitability.

‘Globalisation’, as it was called, meant that wages and benefits in the major economies could not keep up with profits being made abroad; and in the poorer economies, workers’ wages were held down while foreign companies used the latest technology to boost production. Capitalist production in the major economies increasingly switched from traditional sectors like heavy engineering, steel, cars etc into commercial and financial sectors. Profitability rose globally and the share of income going to labour fell back.

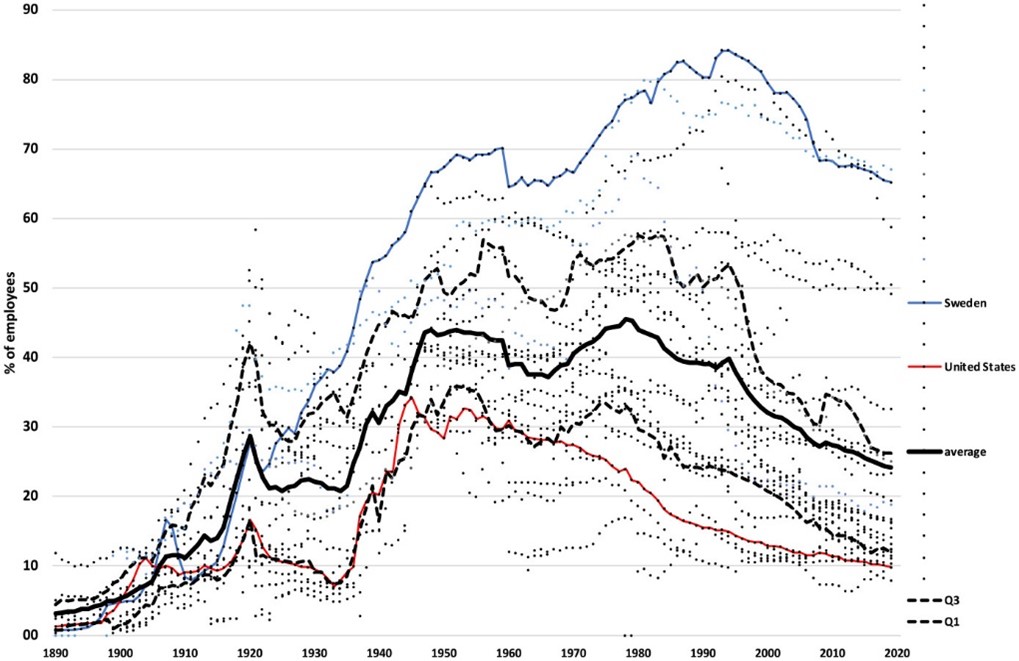

Another key factor in the decline of labour’s share of global income was the decline of trade union organisations. The number of union members as a proportion of employees has more than halved across developed economies from 33.9% in 1970 to just 13.2% in 2019, figures from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) show.

If we look at the development of unionisation in 30 industrial countries over the last 130 years of capitalism, we can observe something like an inverted U-curve, with the peaks of maximum expansion of unionization between 1950 and 1980.

But if we look at the figures now, it seems that the days of trade unions as a force for labour are over. Large firms and manufacturing outlets, the basis for unionism in the past century, have closed or downsized by contracting out tasks and jobs. The growth of commercial services, with on average smaller establishments, has raised the challenge for unions to gain recognition as viable organizations.

Union density rates increase with firm size and this has been the case at least since the 1930s when, for example in the US, unions succeeded in organizing the big companies in steel, oil, cars, shipbuilding and related manufacturing. But the shift from manufacturing in the advanced capitalist economies to so-called ‘services’ has reduced the employment size of most companies. Across the OECD, 63% of all union members are employed in firms of 100+ employees, whereas only 7% work in small firms with 1–9 employees (data for 2015). Of the non-union members, 37% work in 100+ firms and 27% in small firms.

In 2019, 45% of all union members in the OECD worked in the public sector, a rise from 33% in 1980. But over those 40 years the share of public employment – public administration and security, social security, education, health and social assistance – in total employment barely increased, from 19% to 21%. So unionisation in the public sector cannot compensate for the loss of unions in the private sector.

In much of the ‘Global South’, most workers do not even have a permanent job. Globally, 58% of those employed are in what is called ‘informal employment’, amounting to around 2 billion workers in precarious jobs, lacking in any organized defence of their rights at work and their conditions by labour organisations. Increasingly, in many economies, young people experience a high degree of insecurity related to temporary contracts, unemployment and interrupted career paths. Unions appear to them as old and ineffective.

No surprise, then, that only about 2–3% of young workers under the age of 25 join a union. The average union density rate in the OECD of workers under the age of 25 has nearly halved in little more than a decade, from 11% in 2002 to 6% in 2014, continuing a process that began decades ago. In all countries, including high union density countries like Sweden and Denmark, there has been a significant fall in the share of young people joining a union.

Young people’s numbers in unions have correspondingly dwindled. The OECD average is 5.5%, down from an estimated 18% in 1990. Currently the age group of union members nearest to leaving the labour market, i.e. those over 55 years, is four times larger than the 15–24 age group entering the unions. So unions face an uphill battle to replace members who leave with workers who join.

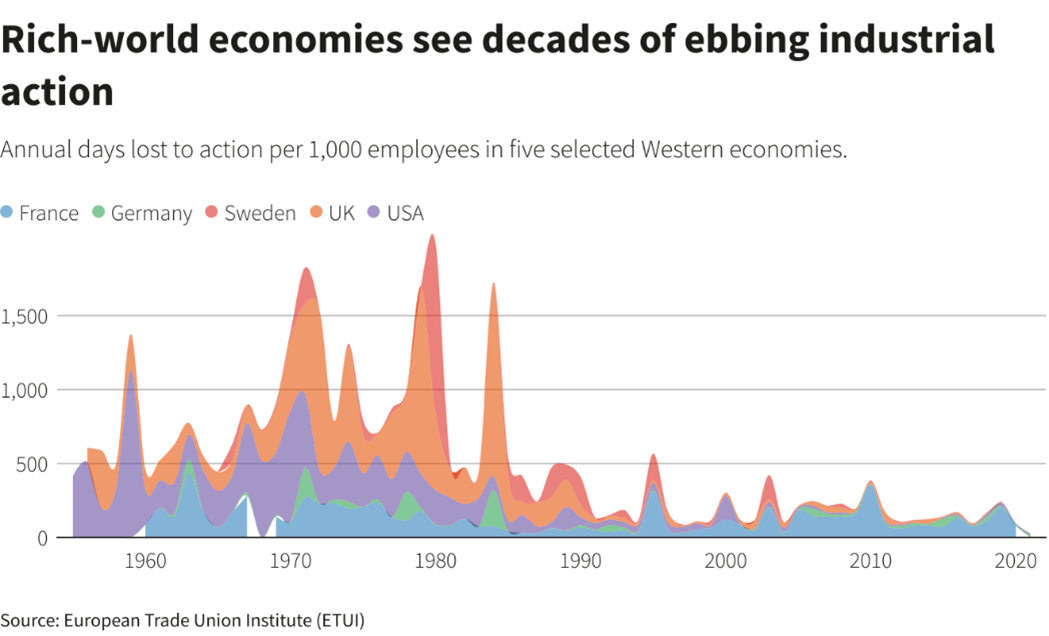

As a result of the weakening of collective labour organizations, workers’ ability to defend their rights at work and gain better wages and conditions has also fallen back. Industrial dispute levels have dropped sharply. Prior to the pandemic slump of 2020, annual days lost due to industrial disputes in the major ‘rich’ economies were near record lows.

In many parts of the Global South, trade unions and collective organisations are banned. According to the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), the Middle East is the worst region for suppressing trade unions. There are no rights in workplaces, independent unions are dismantled and trade union leaders locked up for leading strikes. The kafala system remains in place in several Gulf countries and migrant workers, who represented the overwhelming majority of the working population in the region, remained exposed to severe human rights abuses. In Tunisia, unions feared for democracy and civil liberties as President Kais Saied further consolidated his autocratic powers, while in Algeria and Egypt, independent trade unions still struggled to obtain their registration from hostile authorities and were therefore unable to operate properly. In Lebanon, it was common for employers to interfere in social elections, including by deleting names from the lists of candidates.

That’s all the bad news. But there is also good news coming out of the bad. Millions died unnecessarily in the COVID pandemic and millions more lost their livelihoods in the ensuing slump and the inflationary spiral afterwards. But the pandemic has also changed the balance of forces between labour and capital.

The Black Death and plagues of the 14th century so reduced the population of Europe that labour became so scarce that feudal landlords were forced to make concessions to their serfs, allowing them to earn wages, work less hours for the lord and even gain freedom to become independent farmers. Out of that terrible misery came a period of improved livelihoods.

It seems that a similar development is taking place in this post-pandemic decade of the 21st century. The years of fast-expanding labour markets globally, as in China and eastern Europe, that opened up to capital from the Global North, have come to an end as populations age and shrink. This demographic shift is resulting in a shift in the balance of power between labour and capital.

Amid tight labour markets and a rising cost of living, there has been a resurgence in labour militancy and the conditions for renewed union growth are much more favourable. Unions globally have become increasingly active in the last 12 months in either threatening or carrying out industrial action. For the first time in some 40 years, trade unions are spreading to new industries and sectors in the advanced economies and even into ‘informal’ employment world of the Global South.

In the US, workers have organised and taken to the picket lines in increased numbers to demand better pay and working conditions. Teachers, journalists and baristas are among tens of thousands of workers who have gone on strike in the last year. Indeed, it took an act in the US Congress to prevent 115,000 railroad employees from walking out as well. Workers at Starbucks, Amazon, Apple and dozens of other companies also filed over 2,000 petitions to form unions during the year – the most since 2015. Workers won 76% of the 1,363 elections that were held. There were 33 major work stoppages that began in 2023, the largest number this century.

Elsewhere in the world, we can see something similar. Last March 2023, in Sri Lanka, workers from 40 trade unions, representing sectors including health, energy, financial services and port operations, went on strike over the government’s spending plans in spite of the threat of employees losing their jobs by defying the presidential proclamation.

The South African National Education, Health and Allied Workers Union (NEHAWU) went on strike over pay despite a court order banning industrial action. In India, proposed changes to the country’s labour codes – including clauses requiring 14 days’ notice for strike action brought about strike action.

And even in the Middle East, there have been some successes. Workers at Egypt’s largest textile factory in Mahalla won a major victory for tens of thousands employed across Egypt’s state-owned enterprises by forcing the government to agree to raise the minimum wage to 6000 Egyptian pounds after thousands joined a strike which shut down the mill for nearly a week.

In the past, organized labour was driven by large, central trade unions that coordinated unionization drives, dictated member demands and distributed benefits. By contrast, this new wave of labour organizations are small grassroots unions in untouched sectors, often specific to one company like the Amazon Labor Union and Starbucks Workers United. Moreover, American support for unions has been rising. An August 2023 Gallup poll suggested that two out of three Americans supported unions.

And the battle to defend jobs and conditions against the impact of the new AI technologies has started. An example of this is the recently signed agreement by the Writers Guild of America in Hollywood around concerns of AI adoption by employers in the entertainment industry.

Union revitalization will happen when unions make themselves relevant for both highly-skilled employees and solo self-employed workers (often working from home) and expand their presence among the growing army of mostly young platform workers, migrants and employees with part-time and fixed-term contracts. It will require new methods of reconnecting with young people. More unions now experiment with interactive websites and social media and with a model of membership or participation that is easy and cheap, with low entry or exit costs.

So, in May 2024, we could be at the start of a paradigm shift in labour organization. But trade unions are not enough to change the balance of power between labour and capital. That also requires political action. In Europe, unions were formed by socialist parties in the late 19th century; in the UK, trade unions formed the Labour Party to represent workers in the political arena. The struggle in the workplace can only succeed in making gains when combined with the political struggle to change the whole system of power.

In the 19th century, the struggle for the eight-hour day was a key feature of the May Day marches in the US and Europe. It was only eventually achieved by a combination of union action and political legislation in the 20th century. In the 21st century, the struggle is going to be over AI automation which threatens up to 300m jobs globally in the next decade. The response of labour must be for a four-day week, social support and retraining for those unemployed by the new technology. That will require a combination of new strong unions and political parties dedicated to the struggle of labour over capital.

Courtesy Michael Roberts Blog

Michael Roberts

Michael Roberts worked in the City of London as an economist for over 40 years. He has closely observed the machinations of the global capitalism from within the dragon’s den. Since retiring, he has written several books. The Great Recession – a Marxist view (2009); The Long Depression (2016); Marx 200: a review of Marx’s economics (2018): and jointly with Guglielmo Carchedi as editors of World in Crisis (2018). He has published numerous papers in various academic economic journals and articles in leftist publications.