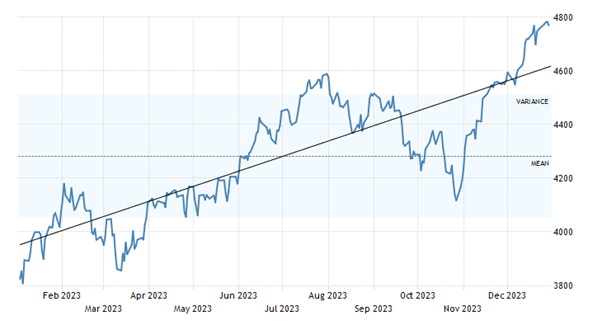

2023 ended with the US stock market hitting a record high.

Financial markets and mainstream economists breathed a sigh of relief that the US economy had not dropped into a recession i.e. technically two consecutive quarters of contraction in real national output. Instead, despite the Federal Reserve hiking its policy rate to a 15-year high, US real GDP rose by about 2.0-2.5% in 2023, possibly slightly higher than in 2022. At the same time, the consumer inflation rate dropped from an average 8% in 2022 to 4.2% in 2023 with the latest figure at just 3.1%. Unemployment did not rise averaging 3.6%, the same as 2022, although there were signs of it ticking up in the last few months.

So the consensus of economic forecasts at the beginning of 2023 proved wrong. As I wrote in my 2023 forecast entitled ‘The impending slump’: “it seems most leading forecasters are agreed – a slump is coming in 2023, even if they hedge their bets on the depth and in which regions.”

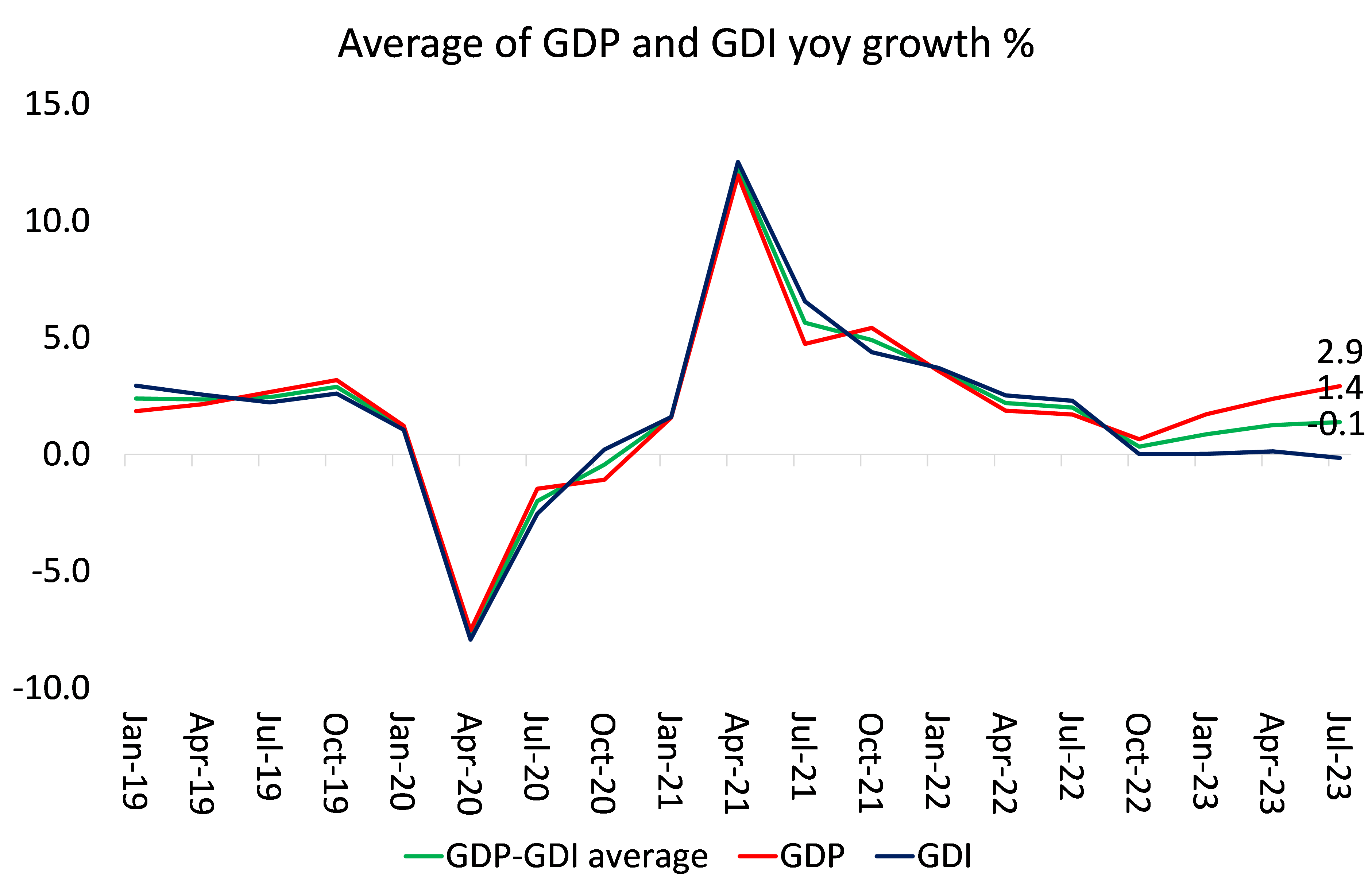

But as I have said in previous posts, the GDP measure seems a bit of an outlier compared to the measure of economic activity based on gross domestic income (GDI). There has been no growth at all in real national income (i.e. profits plus wages). If we average these two different rates, then US economic growth has been about half the GDP rate and considerably slower than in 2022.

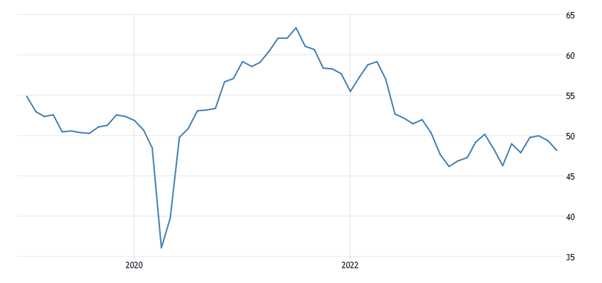

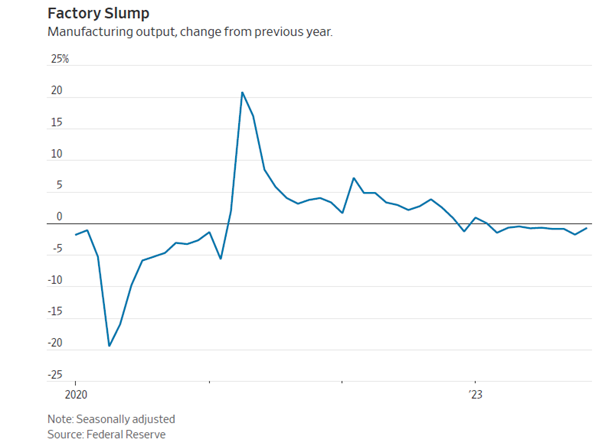

Why the significant difference in 2023? The main reason is that GDP growth has not been transformed into increased sales and revenue at the same rate. Stocks of goods produced have instead built up. US manufacturing industry is in fact mired in the longest slump in more than two decades. Activity in the manufacturing sector has weakened for 13 straight months, the longest stretch since 2002, according to surveys of purchasing managers (PMI) by the Institute for Supply Management.

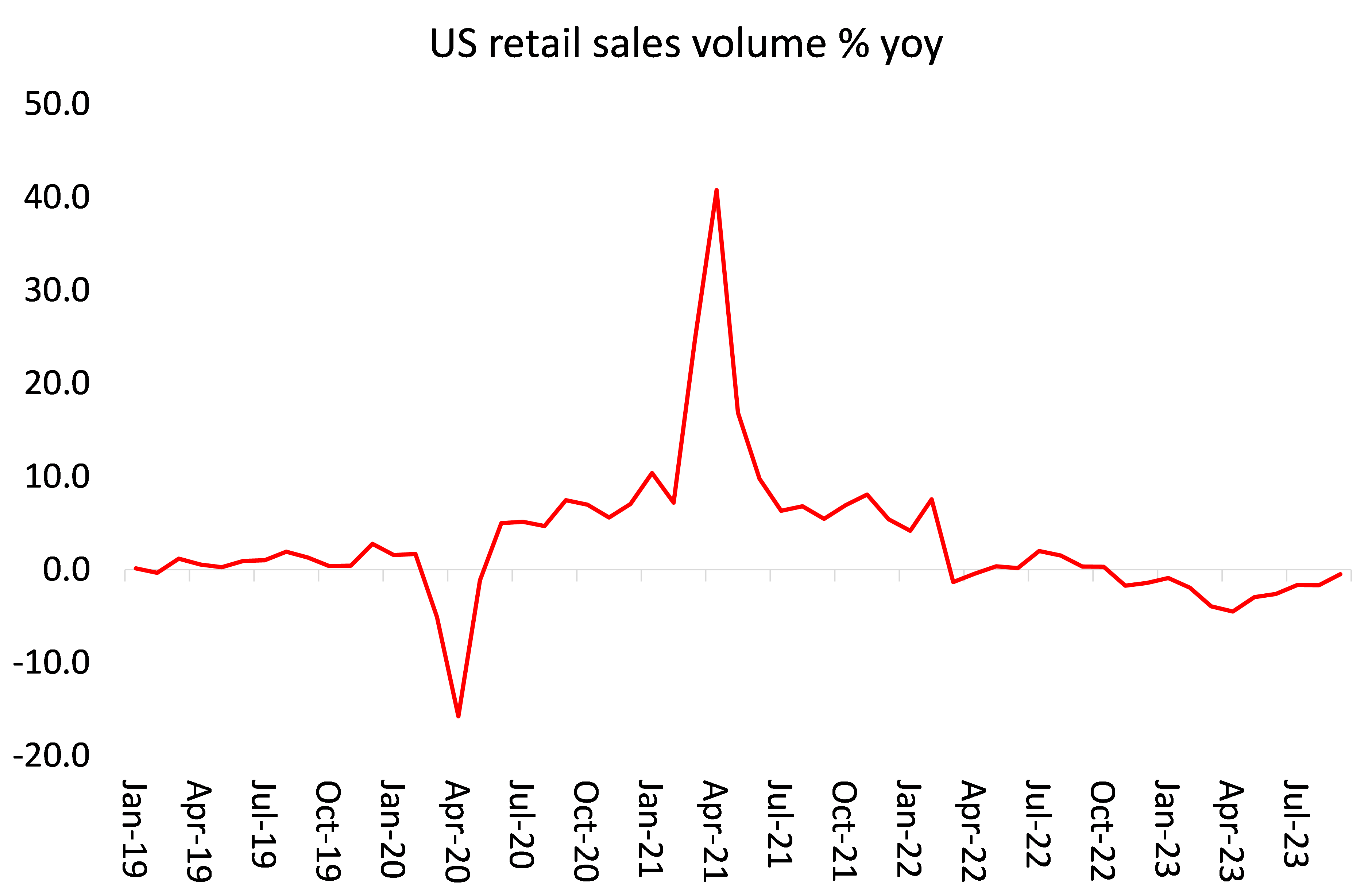

Indeed, when price inflation of goods in the shops and online is accounted for, US retail sales volumes are down compared to 2022.

And manufacturing output is also falling.

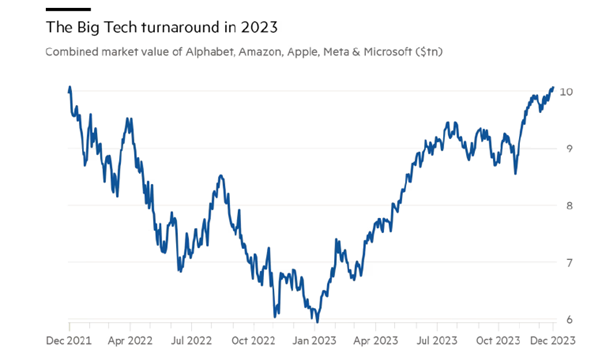

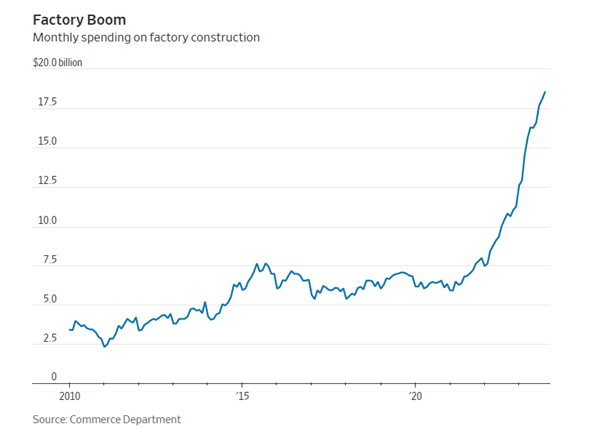

It’s only the large so-called services sector in the US that has expanded. And in that sector, the fastest growth has been in healthcare, education and, of course, technology. Technology boomed in 2023, as government subsidies for technology companies mushroomed. The Inflation Reduction Act offered tax incentives for renewable-energy equipment manufacturers and buyers of electric vehicles. The Chips and Science Act included $39 billion in subsidies for semiconductor makers.

Spending on manufacturing construction (mainly IT) rose almost 40% in 2022 and is up a further 72% through the first 10 months of 2023 versus the same period the previous year.

“You’ve got these acyclical drivers that are really pushing up investment in manufacturing structures just in this one sector, but the broader sector is still struggling,” said Bernard Yaros, lead US economist at Oxford Economics. Investment in factories has occurred in the most high-tech sliver of the sector, while other industries struggle with a pandemic-induced inventory overhang and higher interest rates.

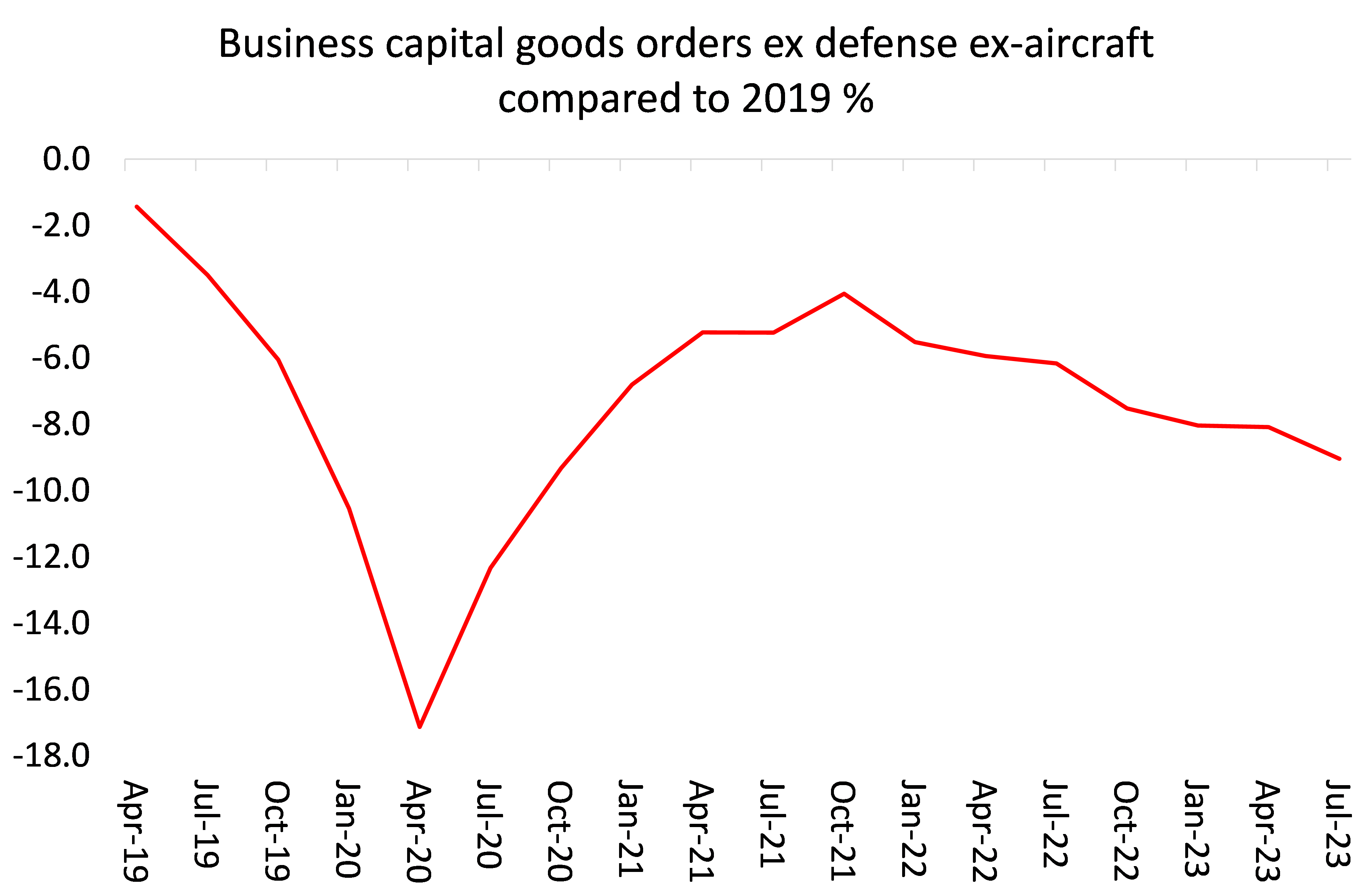

Business orders of capital goods, excluding aircraft and military goods, have been falling for about two years (after adjusting for inflation), according to the Commerce Department.

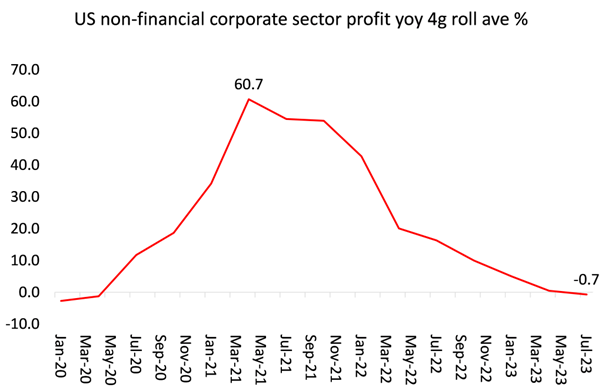

So even if the technology sector is growing and profitable, the rest of US business is not doing so well. Non-financial sector corporate profits are up only 3% on last year so far and are now falling.

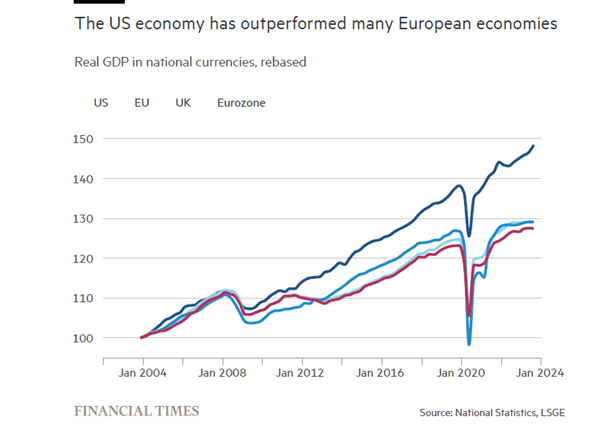

And all this is in the US, the strongest of the G7 economies since the end of the pandemic.

But note, even in the US, the trajectory of growth is lower than before the Great Recession of 2008-9 and is no better than during the average of the 2010s. Europe has performed poorly since the Great Recession and even worse since the end of the pandemic. In 2023, in Europe, Sweden, the Netherlands and Germany entered a recession, with the UK, Italy and France close to it. Canada is in recession and Japan close to it.

But what about 2024? This time, the consensus view is not for a recession in the US or globally. Douglas Porter, chief economist at BMO Capital Markets Economics sums the consensus up. “I expect most major economies to grow more slowly in 2024 than in 2023, but rate cuts, cooling energy and food prices, and normalized supply chains will stave off a global recession.”

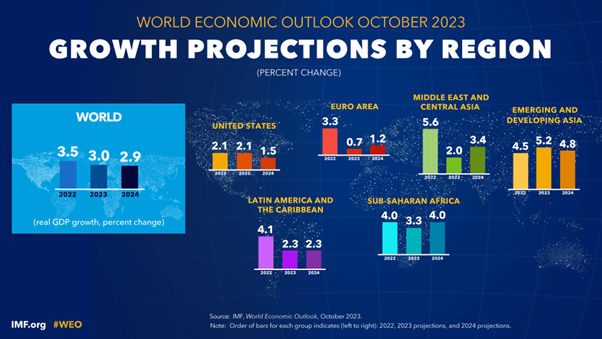

Let’s consider those claims. For a start, the consensus is still for even slower global growth than in 2023. I quote the IMF forecast made in October 2023: “The baseline forecast is for global growth to slow from 3.5 percent in 2022 to 3.0 percent in 2023 and 2.9 percent in 2024, well below the historical (2000–19) average of 3.8 percent. Advanced economies are expected to slow from 2.6 percent in 2022 to 1.5 percent in 2023 and 1.4 percent in 2024 as policy tightening starts to bite. Emerging market and developing economies are projected to have a modest decline in growth from 4.1 percent in 2022 to 4.0 percent in both 2023 and 2024.”

This does not look like a booming 2024 in the US or globally.

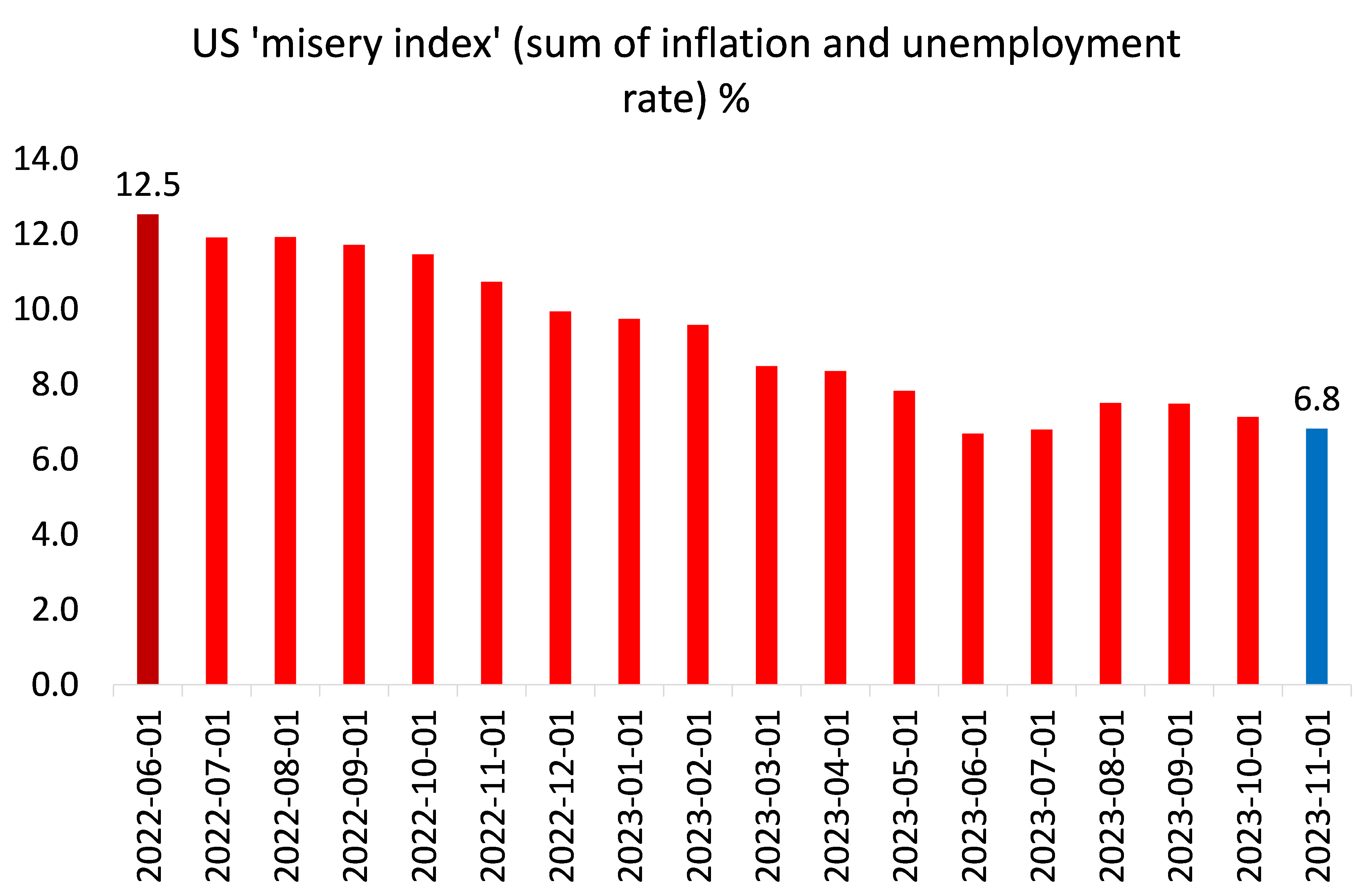

But there seems to be a peak in central bank policy interest rates. So financial markets are now expecting significant reductions during 2024, starting as early as March. Inflation rates are falling everywhere in the major economies and unemployment has not risen – as I showed above. Indeed, the so-called ‘misery index’ (the sum of inflation and unemployment rate) in the US and other major economies has halved 18 months.

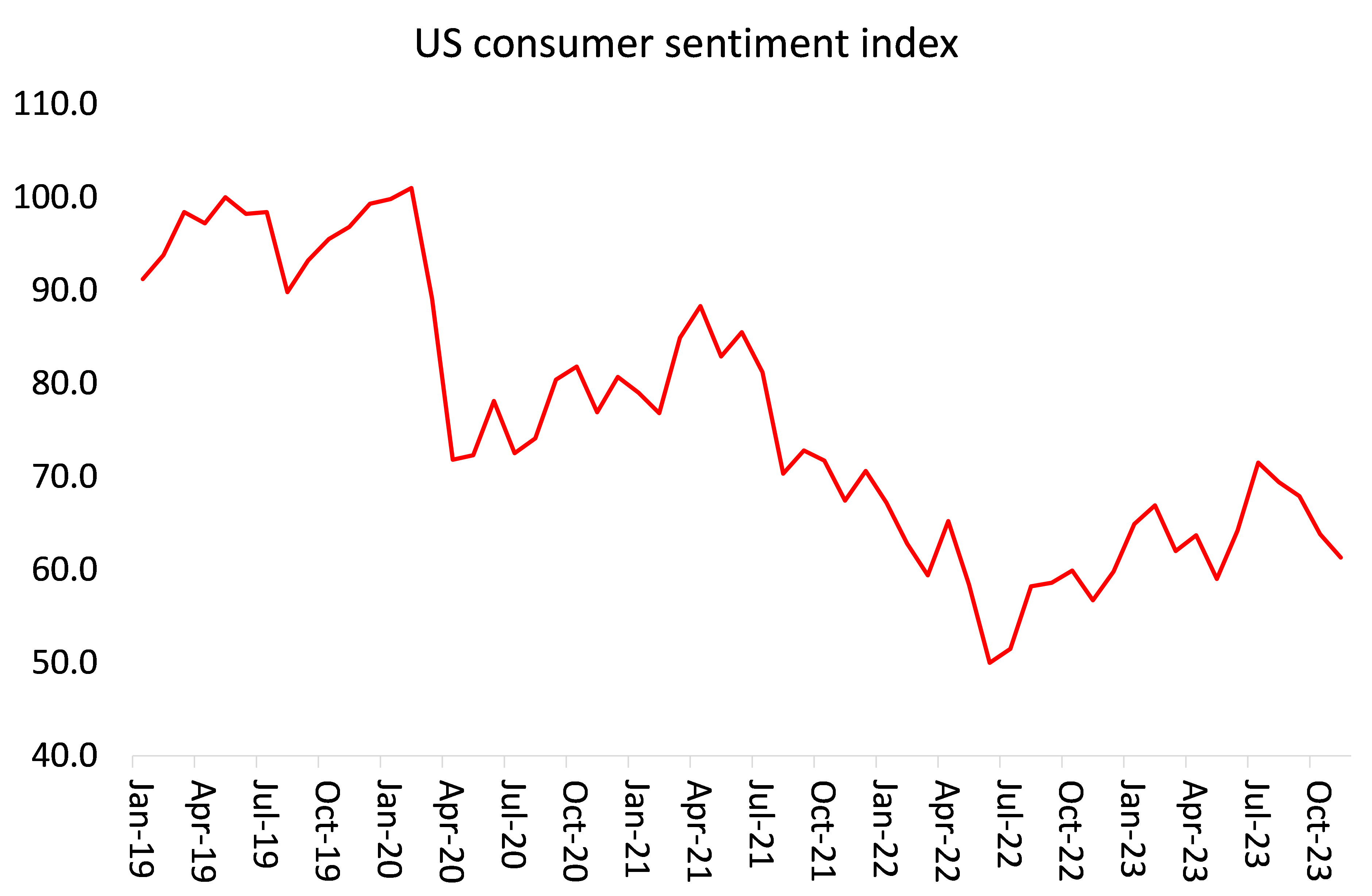

What is puzzling many is that the US economy at least is apparently achieving a ‘soft landing’ from the pandemic, with inflation down, unemployment low and average real incomes beginning to rise, but the American public still seems depressed and uncertain about the future.

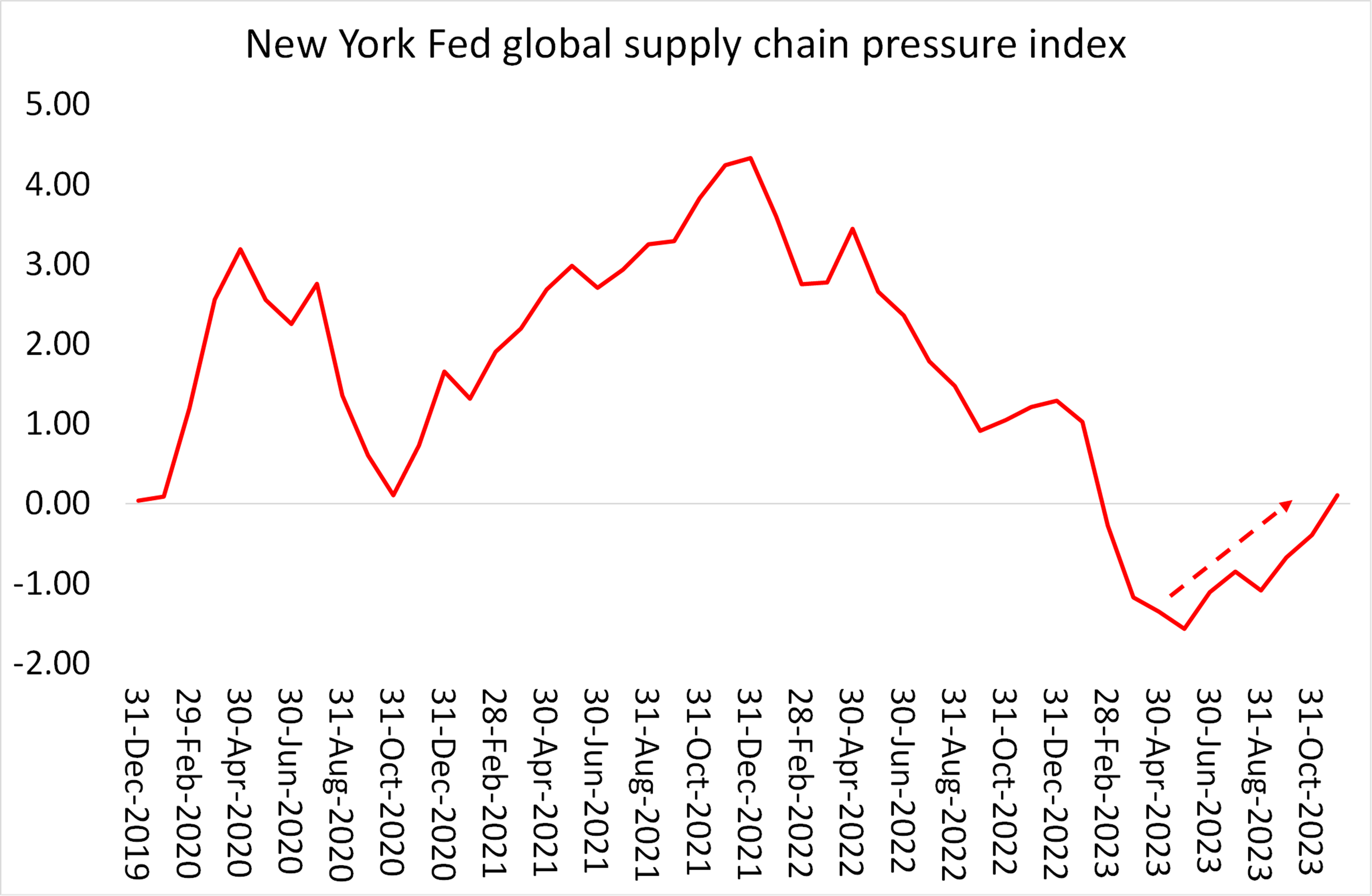

The problem is that inflation has only fallen by half and remains well above the pre-pandemic level of under 2%. And that fall is almost entirely due to the end of supply blockages caused by the pandemic and the eventual fall in energy and food prices. As many have explained, it has had little to do with the monetary policy of the central banks.

The misery index may be down, but most households in the US, Europe and Japan are still suffering the after-effects of the pandemic slump. Prices in Europe and the US are higher by about 17-20% compared to the end of the pandemic. Jobs may be plentiful, but in general they do not pay well and are often part-time or temporary. Moreover, the continuing war in Ukraine and now the horrendous decimation of Gaza could lead to a reversal of the past fall in global supply chain pressure – according to the New York Fed index.

And what is missing from all these optimistic forecasts is the state of so-called emerging or developing economies of the Global South. Take China, India and Indonesia out of the equation and the rest of these economies, particularly the poorest and often most populous, are facing a another year of a severe debt crisis, which has seen mounting defaults by poor country governments and companies on their debt.

I have discussed this in many previous posts and even though interest rates might eventually start falling later in 2024, the impact on the ability of many countries to meet their ‘obligations’ to the rich countries’ investment funds and banks and to the international agencies will be even weaker this year than last.

All this suggests that, although the US economy technically avoided a slump in 2023, which could have triggered a global contraction, the optimistic sounds of this year’s consensus could again prove wrong – this time in the opposite direction.

That’s the economy in 2024. But there is also politics. 2024 is the year of elections. There are 40 national elections slated, the effects of which will cover 41% of the world’s population, in countries representing 42% of global GDP.

The most important election will be the US presidential poll in November, the result of which has the potential to destabilise every economy and financial market. Donald Trump says that the stock market and the economy are only staying strong because everybody expects him to win in November. If he does not, “then there will be a new Great Depression.” Well, that prognosis does not seem likely – indeed the opposite might well be the case if he loses. But there is no certainty about who will win; or whether Biden will actually stand again; or whether either Trump or Biden would even serve another full term.

Russia too has a presidential election, but there the result is clear and guaranteed, not just because the levels of the media, election commissions and state control are entirely in the hands of Putin and any opposition is suppressed, but also because Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has actually boosted his popular support. The Russian economy has avoided a slump and indeed has grown in the last year, driven by mainly military spending.

In Europe, there are the European Assembly elections in June which are expected to see a significant swing to the anti-immigrant, anti-EU integration rightist parties, which are also opposed to further support by the EU for Ukraine. But the current ‘centre’ right pro-Israel, pro Ukraine parties will probably maintain a majority. Portugal holds an election that will almost certainly throw out the Socialists who have been embroiled in a corruption scandal.

And here in the UK there will be a general election this year. The opposition Labour party, now controlled and run by a pro-business right-wing faction, looks set to win over an incompetent and corrupt Conservative government, no longer even supported by its increasingly crazed and aged party members. But a Labour government would merely continue with ‘business as usual’ in both domestic economic policy and in uncritical support for US global hegemony.

The other big election is in India, where again the incumbent ex-fascist president Modi, in power since 2014, looks set to walk the election, given India’s strong economic growth and the disarray of the opposition parties. Across the border, in Pakistan, things will be very tense as the current right-wing government backed by the military aims to defeat the party of former PM Imran Khan, who fell out with the military. In neighbouring Bangladesh, the incumbent autocratic government will win as the opposition is set to boycott the elections.

Votes in Indonesia and South Korea will probably lead to the status quo of pro-capitalist governments. The African National Congress is likely to hang on in South Africa at May elections as the opposition is split, but the ANC may dip below 50% of the vote for the first time since the end of apartheid.

Claudia Sheinbaum, incumbent President Andrés Manuel Lopez-Obrador’s preferred candidate, leads the polls by a huge margin in Mexico. Another key election is in Venezuela. Through an agreement reached with the US, sanctions against the country have been relaxed in return for holding general elections. The US aim is to bring about the end of the Maduro government through a popular vote.

It’s just a fortnight before the general election in Taiwan where the pro-independence governing party looks like retaining the presidency over the more pro-mainland China parties. This could ratchet up the tensions between the US and China.

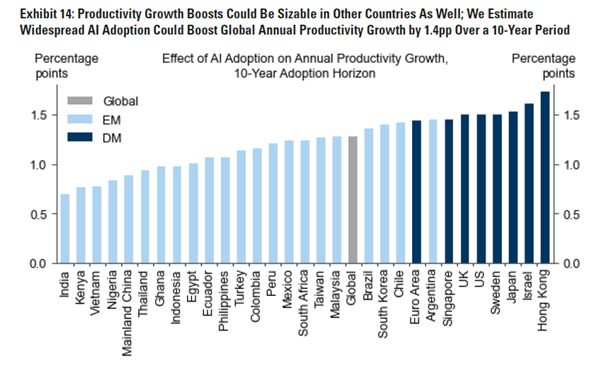

2024 could also be the year when the impact on productivity and jobs of the rise of generative AI becomes clearer. The techno-optimists like Goldman Sachs are drooling at the prospect of sharp increases in US productivity growth over the rest of this decade, mainly achieved by massive reductions of jobs in many service sectors.

In 2024, spending on generative AI next year will amount to little more than $20bn, or 0.5% of total global IT spending, says John-David Lovelock, chief forecaster at IT research firm Gartner. By comparison, IT buyers will spend five times as much on security, he adds. Yet Goldman Sachs estimates that investment in AI will jump in the latter part of this decade to reach more than 2.5% of GDP by 2032.

Even if that happens, that may not deliver a generalised increase in productivity growth. The great internet revolution of the late 1990s produced a stock market boom, bubble and bust, but it did little to boost growth in the overall productivity of labour in the 2000s onwards. As the recently deceased mainstream economic expert on the impact of technology on productivity, Robert Solow, commented at the time, “You can see the computer age everywhere, but in the productivity statistics.” Productivity growth has been slowing globally as a trend throughout the first two decades of this century.

The hope of the optimists is that AI and LLMs will kick-start a ‘roaring 20s’, similar to that experienced in the US after the end of the Spanish flu epidemic from 1918-20 and the subsequent slump of 1920-21. But some things are different now. In 1921, the US was fast-rising manufacturing power, sweeping past war-torn Europe and a declining Britain. Now the US economy is in relative decline, manufacturing is stagnating and the US faces the threat of the rise of China, forcing it to conduct proxy wars globally to preserve its hegemony.

Much more likely is that 2024 will be another year of what I have called a Long Depression that began after the Great Recession of 2008-9, similar to the depression of the late 19th century from 1873-95 in most major economies then. Unless average profitability sharply rises, then business investment growth across the board will remain low even if AI boosts productivity in some sectors. To get a step-change in the profitability of global capital would require a major cleansing (slump) to remove the weak (zombies) and raise unemployment in low-value sectors. So far, such a ‘liquidation’ or ‘creative destruction’ policy has not gained support in the mainstream or in official policy circles. ‘Muddling through’ is better.

In sum, 2024 looks like being one of slowing economic growth for most countries and probably more slipping into recession in Europe, Latin America and Asia. The debt crisis in those countries in the so-called global south that don’t have energy or minerals to sell will worsen. So even if the US avoids an outright slump again this year, it wont feel like a ‘soft landing’ for most people in the world.

Courtesy Michael Roberts Blog

Michael Roberts

Michael Roberts worked in the City of London as an economist for over 40 years. He has closely observed the machinations of the global capitalism from within the dragon’s den. Since retiring, he has written several books. The Great Recession – a Marxist view (2009); The Long Depression (2016); Marx 200: a review of Marx’s economics (2018): and jointly with Guglielmo Carchedi as editors of World in Crisis (2018). He has published numerous papers in various academic economic journals and articles in leftist publications.