This week, the jamboree of the rich global elite of the World Economic Forum (WEF) has started again after the COVID interregnum. Top political and business leaders have flown in on their private jets to discuss climate change and global warming, as well as the impending global economic slump, the cost of living crisis and the Ukraine war.

Their mood is apparently downbeat. Two-thirds of chief economists surveyed by WEF believe there is likely to be a global recession in 2023, with nearly one in five saying it is extremely likely to occur. Corporate leaders are also anxious, with 73% of CEOs around the world reckoning that global economic growth will decline over the next 12-months. That’s the most pessimistic outlook since the WEF survey was first done 12 years ago.

Just before the start of the Forum in the snow of the exclusive ski resort of Davos, Switzerland, the WEF published its Global Risk Report. It makes shocking reading on the state of global capitalism in the 2020s.

The report says that: “the next decade will be characterized by environmental and societal crises, driven by underlying geopolitical and economic trends.” The cost-of-living crisis is ranked as the most severe global risk over the next two years, peaking in the short term. Biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse is viewed as one of the fastest deteriorating global risks over the next decade and all six environmental risks feature in the top ten risks over the next ten years.

The report goes on: “Continued supply-driven inflation could lead to stagflation, the socioeconomic consequences of which could be severe, given an unprecedented interaction with historically high levels of public debt. Global economic fragmentation, geopolitical tensions and rockier restructuring could contribute to widespread debt distress in the next 10 years.” It notes that “technology will exacerbate inequalities; while climate mitigation and climate adaptation efforts are set up for a risky trade-off, as nature collapses. And “food, fuel and cost crises exacerbate societal vulnerability while declining investments in human development erode future resilience.” Apparently, the risk of a ‘polycrisis’ has accelerated.

What do the organisers of the WEF and its participants plan to do about this ‘polycrisis’? Well, the WEF starts from the assumption that capitalism must survive, but the best way to achieve this is by ‘shaping’ capitalism into something “inclusive of all.” Klaus Schwab, the co-founder of the WEF likes to call it ‘stakeholder capitalism’.

Schwab explains: “Generally speaking, we have three models to choose from. The first is “shareholder capitalism,” embraced by most Western corporations, which holds that a corporation’s primary goal should be to maximize its profits. The second model is “state capitalism,” which entrusts the government with setting the direction of the economy, and has risen to prominence in many emerging markets, not least China. But, compared to these two options, the third has the most to recommend it. “Stakeholder capitalism,” a model I first proposed a half-century ago, positions private corporations as trustees of society and is clearly the best response to today’s social and environmental challenges.”

The big corporations should be the ‘trustees of society’ and the main force in solving “today’s social and environmental challenges”. But we need to replace ‘shareholder capitalism’ where “the single-minded focus is on profits so that capitalism becomes increasingly disconnected from the real economy”. According to Schwab, “this form of capitalism is no longer sustainable.” In contrast, the big corporations, in conjunction with governments and multi-lateral organisations, can develop ‘stakeholder capitalism’ instead, which, according to Schwab, can “bring the world closer to achieving shared goals”.

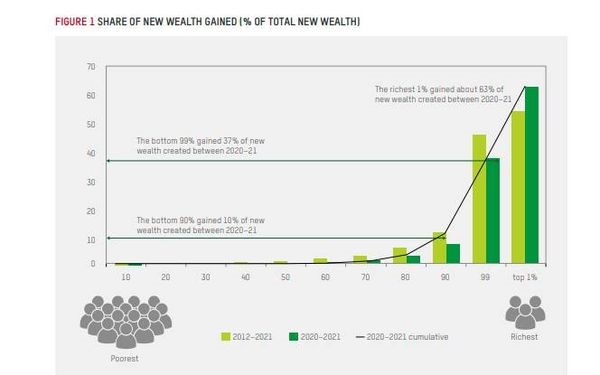

Every year Oxfam releases its annual report on inequality to coincide with the WEF meeting, in order to expose the hypocrisy of ‘stakeholder capitalism’. This year’s report told the story of increased inequality of wealth and incomes since the pandemic. “Over the past two years, the world’s super-rich 1 per cent have gained nearly twice as much wealth as the remaining 99 per cent combined”, Oxfam said.

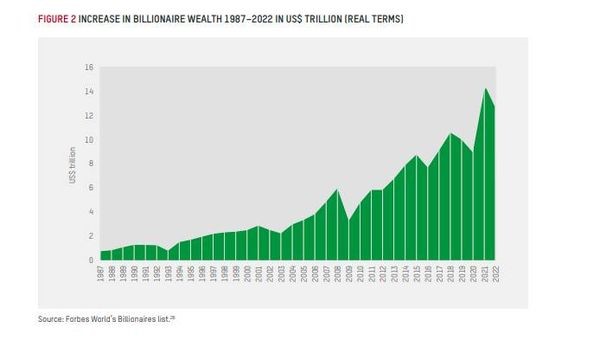

While there are nearly 8 billion people in the world, just over 3,000 are billionaires as of November 2022. This tiny group of people is worth nearly $11.8 trillion – equivalent to about 11.8% of global GDP. Meanwhile, at least 1.7 billion workers live in countries where inflation is outpacing their wage growth, even as billionaire fortunes are rising by $2.7 billion (€2.5 billion) a day.

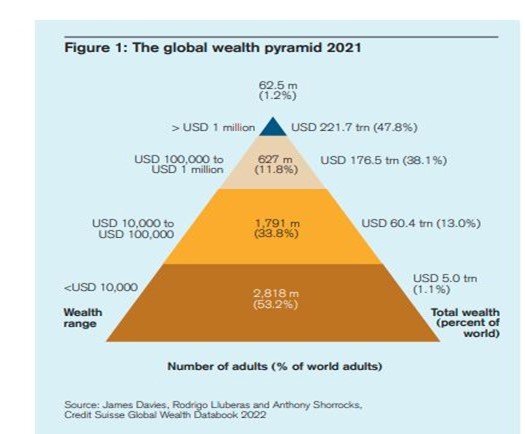

The annual global wealth report from Credit Suisse is the most comprehensive analysis of global personal wealth and its distribution. The 2022 report revealed that by the end of 2021, total global wealth had reached $463.6 trillion, or more than 4.5 times world annual output. Global wealth rose 9.8% in 2021, far above the average annual 6.6% recorded since the beginning of the century. If you exclude the movement of currencies, aggregate global wealth grew by 12.7%, making it the fastest annual rate ever recorded.

This rocketing rise was down to two factors: sharply rising property prices and a credit-fueled stock market boom. So nearly all of this wealth increase went to the richest in the world. Indeed, in 2020, 1% of all adults (56m) in the world owned 45.8% of all personal wealth in the world; while 2.9bn owned just 1.3%. In 2021, that inequality worsened. In 2021, that the top 1% now owned 47.8% of all personal wealth while 2.8bn owned just 1.1%! And the top 13% own 86% of all wealth.

The Oxfam report points out that for every $1 raised in tax, only four cents come from taxes on wealth. The failure to tax wealth is most pronounced in low- and middle-income countries, where inequality is highest. Two-thirds of countries do not have any form of inheritance tax on wealth and assets passed to direct descendants. Half of the world’s billionaires now live in countries with no such tax, meaning $5 trillion will be passed on tax-free to the next generation, a sum greater than the GDP of Africa.

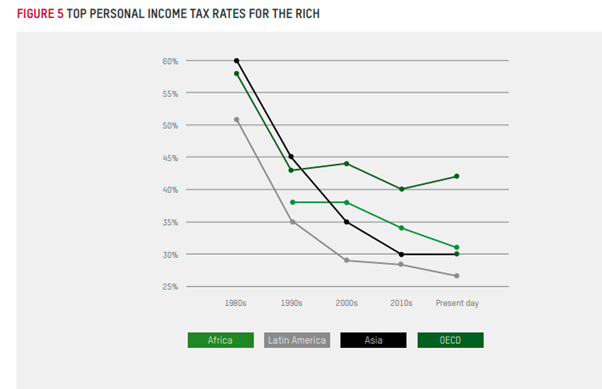

Top rates of tax on income have become lower and less progressive, with the average tax rate on the richest falling from 58% in 1980 to 42% more recently in OECD countries. Across 100 countries, the average rate is even lower, at 31%. Rates of tax on capital gains – in most countries the most important source of income for the top 1% – are only 18% on average across more than 100 countries. Only three countries tax income from capital more than income from work.

Many of the richest men on the planet today get away with paying hardly any tax. For example, one of the richest men in history, Elon Musk, has been shown to pay a ‘true tax rate’ of 3.2%, while another of the richest billionaires, Jeff Bezos, pays less than 1%.

Oxfam’s policy answer is to tax the rich. Oxfam calls for a tax of up to 5% on the world’s multi-millionaires and billionaires that could raise $1.7 trillion a year “enough to lift 2 billion people out of poverty and fund a global plan to end hunger. “The eventual aim should be to go further, and to abolish billionaires altogether, as part of a fairer, more rational distribution of the world’s wealth.”

The question that will be naturally asked is how realistic is it to expect that governments that support ‘stakeholder capitalism’ are likely to introduce higher taxes on wealth and income, let alone abolish all billionaires through taxation? That is going to require mass struggle to bring governments of working people to power to work in coordination globally. In which case, why stop at taxing the rich but instead aim to end capitalism altogether.

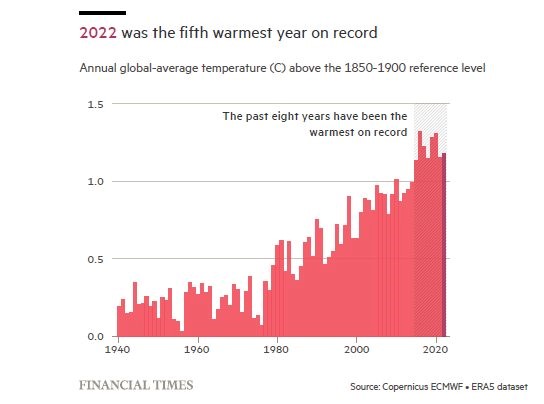

It’s same story with climate change. COP 27 and COP 15 were complete ‘cop-outs’ in trying to meet even the Paris COP target of limiting global average temperatures to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels. Last year was the fifth warmest on record, with the average global temperature almost 1.2C above pre-industrial levels, according to the EU’s earth observation programme.

The year was marked by 12 months of climate extremes, with Europe registering its hottest summer on record despite the presence for the third year in a row of the La Niña phenomenon that has a cooling effect, Copernicus Climate Change Service found in its annual round-up of the earth’s climate. At the same time, US greenhouse gas emissions rose again in 2022, putting the country further behind its targets under the Paris climate agreement despite the passage of sweeping clean energy legislation last year.

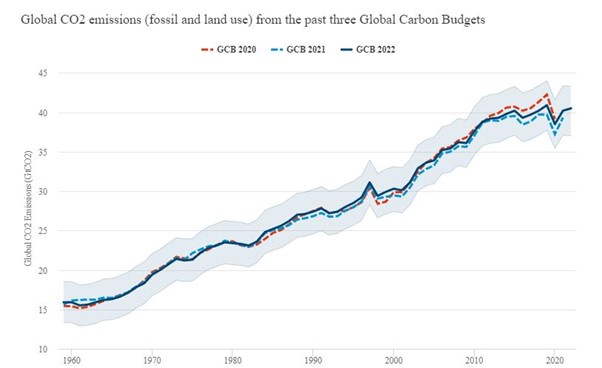

Global carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels and cement increased by 1.0% in 2022, hitting a new record high of 36.6bn tonnes of CO2 (GtCO2). Emissions “are approximately constant since 2015” due to a modest decline in land-use emissions balancing out modest increases in fossil CO2. But remember, stable emission levels are not enough to stop the world continuing to heat up beyond official target limits. A 50% reduction in emissions by the end of this decade and zero emissions by the end of the century are needed at the very least.

Instead, US emissions increased by 1.3 per cent last year, according to preliminary estimates by environmental consultancy Rhodium Group, led by sharp increases from the country’s buildings, industry and transport. “With the slight increase in emissions in 2022, the US continues to fall behind in its efforts to meet its target set under the Paris Agreement of reducing GHG emissions 50-52 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030,” the authors said. Last year, US emissions were just 15.5 per cent below 2005 levels.

But don’t worry, the US spokesman on climate, John Kerry, was at Davos this week to complain about slow progress. And former Bank of England governor, Mark Carney, now the organizer among international banks of a climate financing fund, was also there to complain about slow progress. I am sure that will lead to action.

And then there is the state of the world economy itself. Just before Davos, IMF chief Kristalina Georgieva warned that a third of the global economy would be hit by recession this year. The IMF reckons that global real GDP growth will be just 2.7% in 2023. That is officially not a recession in 2023 – “but it will feel like one”. And the IMF is set to lower its forecasts again at the end of this month. “Risks to the outlook remain unusually large and to the downside,”.

And the IMF’s forecast is the most optimistic. The OECD reckons global growth will slow to 2.2% next year. “The global economy is facing significant challenges. Growth has lost momentum, high inflation has broadened out across countries and products, and is proving persistent. Risks are skewed to the downside.” Then UNCTAD, in its latest Trade and Development report, also projects that world economic growth will drop to 2.2% in 2023. “The global slowdown would leave real GDP still below its pre-pandemic trend, costing the world more than $17 trillion – close to 20% of the world’s income.”

The World Bank’s latest Global Economic Prospects report is even more pessimistic. The WB reckons that global growth will slow to its third-weakest pace in nearly three decades, overshadowed only by the 2009 and 2020 global recessions. It will be a sharp, long-lasting slowdown, with global growth declining to 1.7% in 2023, with the deterioration broad-based: in virtually all regions of the world, per-capita income growth will be slower than it was during the decade before COVID-19. And that was the decade of what I call the Long Depression. By the end of 2024, GDP levels in developing economies will be about 6% below the level expected on the eve of the pandemic.

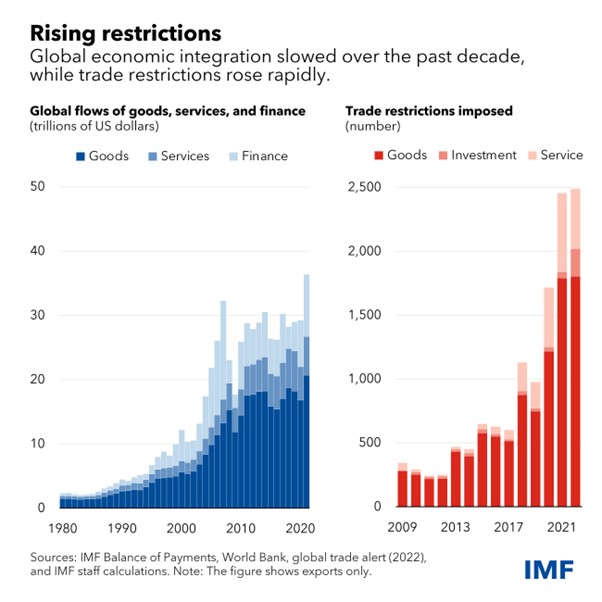

Then there are the growing geopolitical tensions. – not just the Russia-Ukraine conflict but the increasing ‘fragmentation’ of the world economy. The US hegemony, built round ‘globalisation’ and the Great Moderation of the 1980s up to the 2000s, is over.

Georgieva is particularly worried. In her pre-Davos message, she groaned: “we are facing the specter of a new Cold War that could see the world fragment into rival economic blocs”. The gains of globalisation could be “squandered”. But it’s another myth that ‘globalisation’ benefited the majority. Georgieva says that “since the end of the Cold War, the size of the global economy roughly tripled, and nearly 1.5 billion people were lifted out of extreme poverty.” But what improvement in global output and living standards that has been achieved has been confined mainly to China and East Asia. World economic growth has slowed since the 1990s and poverty has not been reduced for some 4bn on the planet, while inequality has risen (as revealed above).

Georgieva wants to reverse the surge in new trade restrictions which is “a dangerous slippery slope towards runaway geoeconomic fragmentation”. She reckons that the longer-term cost of trade fragmentation alone could range from 0.2 percent of global output in a ‘limited fragmentation’ scenario to almost 7 percent in a ‘severe scenario’ —roughly equivalent to the combined annual output of Germany and Japan. If technological decoupling is added to the mix, some countries could see losses of up to 12 percent of GDP. Globalisation increased inequalities and and did not deliver on reducing poverty; fragmentation is likely to intensify those outcomes.

What is Georgieva’s answer to all this? First, strengthen the international trade system. Second, help vulnerable countries deal with debt. Third, step up climate action. She summed up: “The discussions in Davos will be a hopeful sign that we can move in the right direction and foster economic integration that brings peace and prosperity to all.” Some hope. Davos wants to ‘shape’ capitalism, but instead it’s going pear-shaped.

Courtesy Michael Roberts Blog

Michael Roberts

Michael Roberts worked in the City of London as an economist for over 40 years. He has closely observed the machinations of the global capitalism from within the dragon’s den. Since retiring, he has written several books. The Great Recession – a Marxist view (2009); The Long Depression (2016); Marx 200: a review of Marx’s economics (2018): and jointly with Guglielmo Carchedi as editors of World in Crisis (2018). He has published numerous papers in various academic economic journals and articles in leftist publications.