COP 27 started over the weekend. COP stands for the conference of the parties under the UNFCCC. Under the 1992 UN framework convention on climate change (UNFCCC), every country is treaty-bound to “avoid dangerous climate change” and find ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions globally in an equitable way. At the 2015 COP in Paris, countries committed to holding global temperature rises to “well below” 2C above pre-industrial levels, while “pursuing efforts” to limit heating to 1.5C. Those goals are supposedly legally binding and enshrined in the treaty. However, to meet those goals, countries also agreed on non-binding national targets to cut – or in the case of developing countries to curb – the growth of greenhouse gas emissions in the near term, by 2030 in most cases. Those targets are known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs).

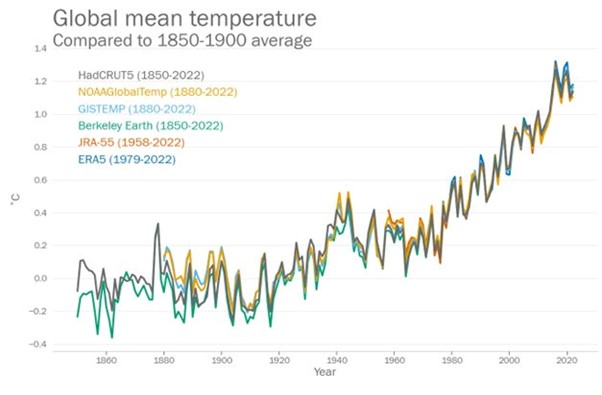

As the international COP 27 climate change conference opened in Sharm-el-Sheikh, Egypt, the UN released a new report finding that the last eight years were the hottest ever recorded and the chances of keeping the world temperature from rising more than the international target limit 1.5C compared to pre-industrial times was ‘barely possible’.

The rate of sea level rise has doubled since 1993. It has risen by nearly 10 mm since January 2020 to a new record high this year. The past two and a half years alone account for 10 percent of the overall rise in sea level since satellite measurements started nearly 30 years ago. Extreme heatwaves, drought and devastating flooding have already affected millions and cost billions this year.

Temperatures in Europe have increased at more than twice the global average in the last 30 years, according to a report from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). From 1991 to 2021, temperatures in Europe have warmed at an average rate of about 0.5C a decade. This has had physical results: alpine glaciers lost 30 metres in ice thickness between 1997 and 2021, while the Greenland ice sheet has also been melting, contributing to sea level rise. In summer 2021, Greenland had its first ever recorded rainfall at its highest point, Summit station.

Human life has been lost as a result of the extreme weather events. The report says that in 2021, high impact weather and climate events – 84% of which were floods and storms – led to hundreds of fatalities, directly affected more than 500,000 people, and caused economic damages exceeding $50bn. Disaster is already here.

If global warming continues, scientists predict even more devasting disasters and long-term disruption to weather patterns that would destroy lives and livelihoods and upend societies. Mass migration could follow. And failure to get emissions on the right trajectory by 2030 may lock global warming above 2 degrees celsius and risk catastrophic tipping points—where climate change becomes self-perpetuating.

According to major study, the world is on the brink of multiple “disastrous” tipping points. The study shows five dangerous tipping points that may already have been passed due to the 1.1C of global heating caused by humanity to date. These include the collapse of Greenland’s ice cap, eventually producing a huge sea level rise, the collapse of a key current in the north Atlantic, disrupting rain upon which billions of people depend for food, and an abrupt melting of carbon-rich permafrost. At 1.5C of heating, the minimum rise now expected, four of the five tipping points move from being possible to likely, the analysis said. Also at 1.5C, an additional five tipping points become possible, including changes to vast northern forests and the loss of almost all mountain glaciers

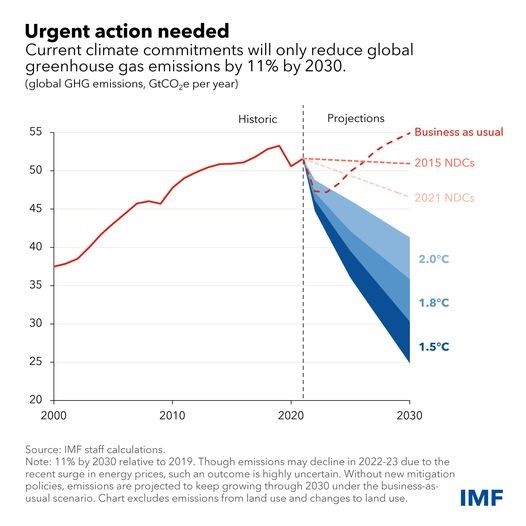

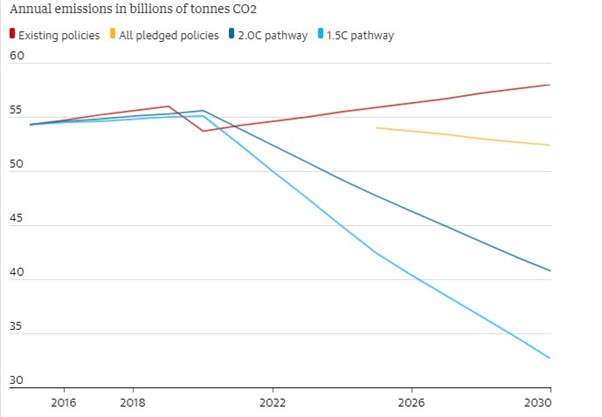

Are countries getting to net zero carbon emissions? Nowhere near close, says IMF in a new report. Net-zero rhetoric does not match reality. New IMF analysis of current global climate policies shows they would only deliver an 11 percent cut. “The gap between that and where we need to be is massive—equivalent to more than five times the current annual emissions of the European Union.”

And the UN’s environment agency has said: “There is “no credible pathway to 1.5C in place”, The UN environment report analysed the gap between the CO2 cuts pledged by countries and the cuts needed to limit any rise in global temperature to 1.5C, the internationally agreed target. Progress has been “woefully inadequate” it concluded. Current pledges for action by 2030, if delivered in full, would mean a rise in global heating of about 2.5C and catastrophic extreme weather around the world. A rise of 1C to date has caused climate disasters in countries from Pakistan to Puerto Rico.

Even if the long-term pledges by countries to hit net zero emissions by 2050 were delivered, global temperature would still rise by 1.8C. But the glacial pace of action means meeting even this temperature limit was not credible, the UN report said. Instead, the report found that existing carbon-cutting policies would cause 2.8C of warming, while pledged policies cut this to 2.6C. Further pledges, dependent on funding flowing from richer to poorer countries, could cut this – but only to 2.4C.

The International Energy Agency warned last year that no new fossil fuel development should take place if the world was to stay within 1.5C. “If these developments are not swiftly curtailed they could be disastrous for hopes of avoiding the worst ravages of climate breakdown.” Instead, because of energy crisis and the war in Ukraine, some EU countries have also returned – temporarily, they insist – to coal-fired power generation and embarked on a hunt for new fossil fuel supplies, building liquefied natural gas terminals and seeking deals with countries in Africa and elsewhere to explore new gas fields.

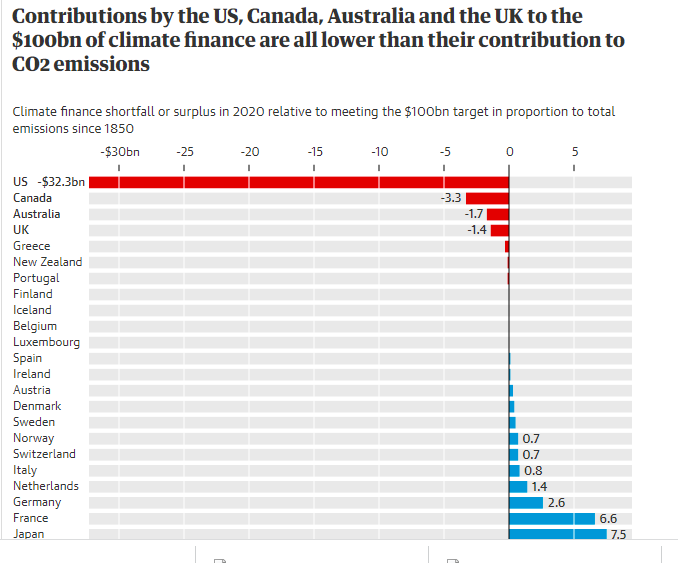

Can the environmental disaster that is already with us be curbed and even reversed? Well, it won’t if we have to rely on private finance and capital. Even the limited commitments by private capital to funding climate mitigation have not been kept. The US, UK, Canada and Australia have fallen billions of dollars short of their “fair share” of climate funding for developing countries.

An assessment by Carbon Brief, compared the share of international climate finance provided by rich countries with their share of carbon emissions to date, a measure of their responsibility for the climate crisis. Rich countries have pledged to provide $100bn a year by 2020. The US share of this, based on its past emissions, would be $40bn yet it provided only $7.6bn in 2020, the latest year for which data is available. Australia and Canada gave only about a third of the funding indicated by the analysis, while the UK supplied three-quarters but still fell $1.4bn short.

Nafkote Dabi, the climate change policy lead at Oxfam International, said: “Rich countries continue to fail to deliver their long-standing pledge of $100bn a year. The failure is all the more stark when you consider that the $100bn is minuscule compared to what is required to address the climate crisis.” And the head of the V20 group of most climate-vulnerable nations representing 1.5 billion people in 58 countries. reckons that these countries have already suffered $500bn in losses because of climate impacts. “Currently we face a debt crisis because so many of the assets that we took loans to pay for are being destroyed by climate change.” And yet, at the very start of COP27 there was a bitter row to get a discussion of these losses and funding for the V20 on the agenda.

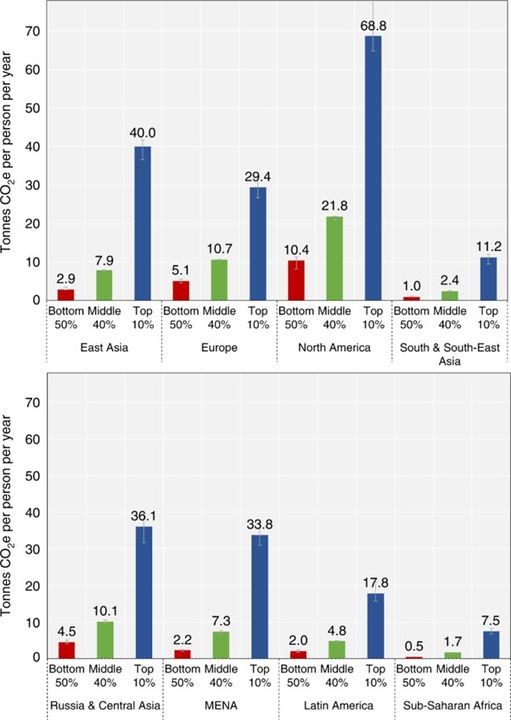

While the poor countries suffer the impact of global warming with little or no support, the rich go on investing in carbon intensive industries. According to a new report by Oxfam, the super-rich emit greenhouse gases at a level equivalent to the whole of France from their investments in carbon intensive businesses. Examining the carbon impact of the investments of 125 billionaires, Oxfam found they had a collective $2.4tn stake in 183 companies. On average each billionaire’s investment emissions produced 3m tonnes of CO2 a year; a million times more than the average emissions of 2.76 tonnes of CO2 for those living in the bottom 90% of earners. In total, the 125 members of the super-rich emitted 393m tonnes of CO2 a year – equivalent to the emissions of France, which has a population of 67 million.

And then there is war, not just in Ukraine but everywhere. US military pollution is a significant contributor to climate change. If it were a nation state, it would be the 47th largest emitter in the world. In 2019, a report released by Durham and Lancaster University found the US military to be “one of the largest climate polluters in history, consuming more liquid fuels and emitting more CO2e (carbon-dioxide equivalent) than most countries”. The US military was also found to have purchased 269,230barrels of oil a day and emitted more than 25,000 kt of carbon dioxide. The Cost of Wars Project found that US military pollution had accounted for 1.2 billion metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions, which amount to 257million passenger cars annually. They compared this astonishing output as higher than the emissions from whole countries like Sweden, Morocco, and Switzerland.

Yet again the powers-that-be from the IMF, World Bank and even the UN, look only to market solutions to deal with climate change. At COP27, US president Joe Biden’s climate envoy John Kerry is trying to marshal support from other governments, companies and climate experts to develop a new framework for carbon credits to be sold to business. The proceeds could then fund new clean energy projects, so Kerry argues. Kerry says that the private sector could be “enticed” to the table because it would offer the most-polluting companies a way of addressing their emissions. But carbon credits are really a method of avoiding cutting emissions for companies as they can just buy their way out of doing anything. And there is no guarantee that money raised would be used to reduce fossil fuel output.

Private finance won’t decarbonise the planet – only public investment can do so argues leftist economist Daniela Gabor. “We cannot rely on private finance to lead us out of a climate crisis it has systematically contributed to. We have to disempower carbon financiers, and we do that by making the democratic state – not investors – lead the way forward.”

And this is what I wrote at the time of COP26 in Glasgow last year: “market solutions will not do the trick, as again the COVID pandemic has shown. Only government intervention, investment and planning on a global scale can give humanity and nature a chance to succeed before too much degradation is made permanent. Carbon pricing will not allocate investment properly or change consumption sufficiently – and it only benefits the richer countries (1bn people) at the expense of the poorer (6.5bn)….Private finance organised by banks and investment funds will not deliver. That’s because capitalist companies control and make decisions on investment based on profitability. Global warming will not be stopped or reversed without ending fossil fuel and mining exploration and phasing out fossil fuel production. Nothing like that is on the agenda of COP26.” And neither is it on the agenda of COP27.

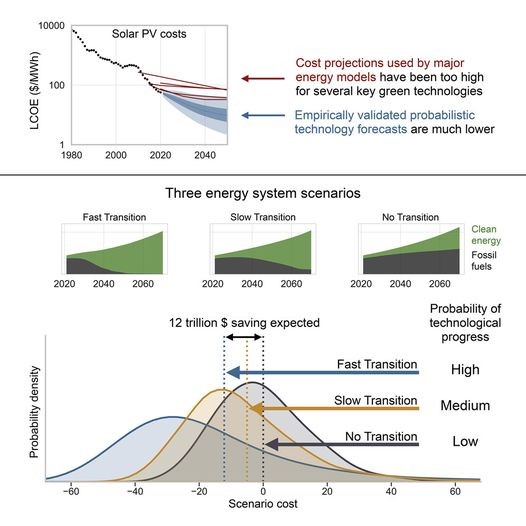

In my view, a transition to a decarbonised energy system can only happen if it is organized globally and funded and implemented by state investment. A recent study offers a realistic future of a near fossil-free energy system by 2050, providing 55% more energy services globally than today, with large amounts of wind, solar, batteries, electric vehicles, and clean fuels such as green hydrogen (made from renewable electricity). Such a net-zero carbon future is not only technically feasible, but the research shows it is expected to cost the world $12 trillion less than continuing with the polluting fossil fuel-based system we have today.

We won’t control or reverse (if that’s still possible) greenhouse gas emissions and rising global temperatures in a capitalist world economy that supports and finances the fossil fuel industry. Nor will it happen while the extreme rich who control the decisions of government and companies continue to invest in carbon-intensive businesses.

Courtesy Michael Roberts Blog

Michael Roberts

Michael Roberts worked in the City of London as an economist for over 40 years. He has closely observed the machinations of the global capitalism from within the dragon’s den. Since retiring, he has written several books. The Great Recession – a Marxist view (2009); The Long Depression (2016); Marx 200: a review of Marx’s economics (2018): and jointly with Guglielmo Carchedi as editors of World in Crisis (2018). He has published numerous papers in various academic economic journals and articles in leftist publications.