If anything proves that famine and food insecurity are man-made rather than due to vagaries of nature and the weather, it is the current food crisis that is putting millions globally close to starvation.

The Russia-Ukraine war has highlighted the global food supply disaster but this was brewing well before the war. The food supply chain has been increasingly global. The Great Recession of 2008-9 began to disrupt that chain, based as it was on multi-national food companies controlling the supply from farmers across the world. These companies directed demand, generated the fertiliser supply and dominated much of the arable land. When the Great Recession struck, they lost profits, and so cut back on investment and increased pressure on food producers in the ‘Global South’.

The cracks in these fundamentals of food supply were accompanied by rising oil prices, explosive demand for corn-based biofuels, high shipping costs, financial market speculation, low grain reserves, severe weather disruptions in some major grain producers, and increased protectionist trade policies. This was the food ‘climate’ in the long depression up to 2019, before the pandemic struck.

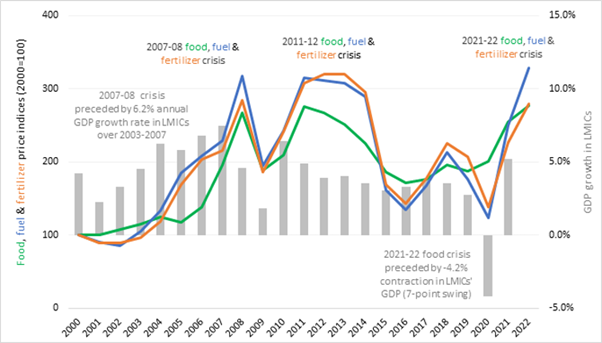

Food, fuel and fertiliser prices versus GDP growth in low- and middle-income countries, 2000-2022. FAO/IMF/World Bank.

The food crisis after the Great Recession was relatively short lived but was followed by another food price explosion in 2011-12. Finally, the ‘commodities boom’ ended and food prices were relatively stable for a while. But the pandemic slump provoked a new crisis as the global supply chain collapsed, shipping costs rocketed and fertiliser supply dried up. The cereal price index showed prices hit their 2008 level in 2021.

The world has not recovered from the tailwinds of the COVID-19 pandemic, the worst economic crisis since the second world war. And this is at a time when many economies face large debt burdens relative to national income. Africa is the most vulnerable region. North Africa is a huge net importer of wheat, most of which comes from Russia and Ukraine, so it faces a particularly acute food crisis. Sub-Saharan Africa is predominantly rural, but its growing urban populations are relatively poor and more likely to consume imported grains. Farmers in many parts of Africa are struggling to access fertilisers, even at inflated prices, due to shipping and foreign exchange problems. Exorbitantly high costs will erode farmers’ profits and could reduce incentives to increase production, dampening the poverty-reduction benefits of higher food prices.

Countries already affected by conflict and climate change are exceptionally vulnerable. War-ravaged Yemen is heavily dependent on imported grains. Northern Ethiopia is one of the poorest regions on Earth, facing ongoing conflict and a humanitarian crisis. And Madagascar was slammed by successive tropical storms and cyclones in January and February, leaving its food system broken. In Afghanistan, child mortality rates are soaring due to the collapse of the economy and basic health services. Myanmar’s GDP shrunk by 18% after the military coup in February 2021.

The Russia-Ukraine war only exacerbated this food security and price disaster. Russia and Ukraine account for more than 30% of global grain exports, Russia alone provides 13% of global fertiliser and 11% of oil exports, and Ukraine supplies half of the world’s sunflower oil. In combination, this is huge a supply shock to the global food system, and a protracted war in Ukraine and the growing isolation of Russia’s economy could keep food, fuel and fertiliser prices high for years.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has sent the global food price index to an all-time high. The invasion idled Ukraine’s once-busy Black Sea ports and left fields untended, while curbing Russia’s ability to export. The pandemic continues to snarl supply chains, while climate change threatens production across many of the world’s agricultural regions, with more drought, flooding, heat, and wildfires.

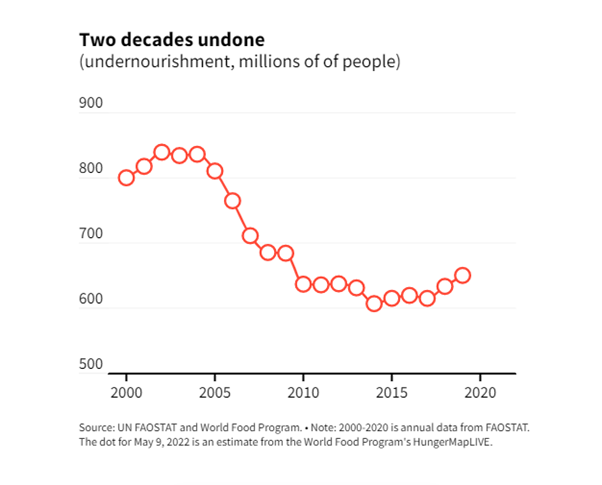

Millions are being driven towards starvation according to the World Food Program. Those considered ‘undernourished’ rose by 118 million people in 2020 after remaining largely unchanged for several years. Current estimates now put that number at about 100 million more.

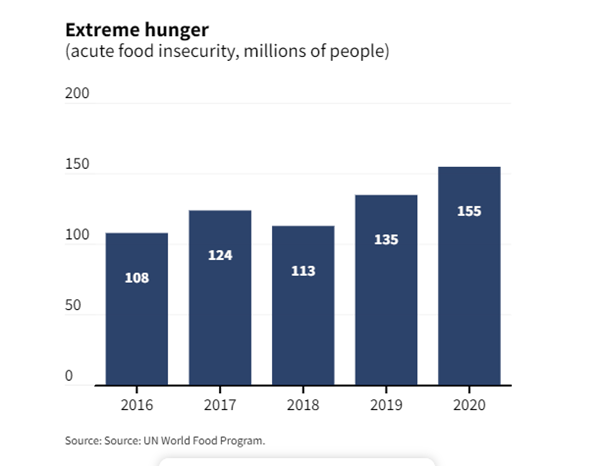

Acute hunger levels—the number of people who can’t meet short-term food consumption needs – rose by nearly 40 million last year. War has always been the main driver of extreme hunger and now the Russia-Ukraine war is adding to the risk of hunger and starvation for many millions more.

IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva: “For several countries, this food crisis comes on top of a debt crisis. Since 2015 the share of low-income countries at or near debt distress has doubled, from 30 to 60%. For many, debt restructuring is a pressing priority … We know hunger is the world’s greatest solvable problem. A looming crisis is the time to act decisively—and solve it.”

But the mainstream solutions to this disaster are either inadequate or utopian, or both. The call is for the ‘major grain producers’ to resolve logistical bottlenecks, release stocks and resist the urge to impose food export restrictions. The oil-producing nations should increase fuel supplies to help bring down fuel, fertiliser and shipping costs. And governments, international institutions and even the private sector must offer social protection via food or financial aid.

None of these proposals is happening. Very little is being done by the major capitalist powers to help those poor countries with the starving and malnourished millions. At the end of last month, the European Commission announced a €1.5 billion aid package, along with additional measures, to support farmers in the EU and protect the bloc’s food security . The leaders of the World Bank Group, International Monetary Fund, United Nations World Food Program, and World Trade Organization called for urgent, coordinated action to address food security. Fine words but no action.

A real help would be to cancel the debts of the poor countries. But all that the IMF and the major powers have offered is a debt service suspension – the debts remain but the repayments can be delayed. Even this ‘relief’ is pathetic. In total, over the last two years, the G20 governments have suspended just $10.3 billion. In the first year of the pandemic alone, low-income countries accumulated a debt burden totalling $860 billion, according to the World Bank.

The other IMF ‘solution’ was to increase the size of Special Drawing Rights, the international money, to be used for extra aid. The IMF injected $650 billion of aid through the SDR program. But because of the ‘quota’ system for the distribution of SDRs, SDR quotas are disproportionately tilted toward rich countries: Africa received less SDRs than the German Bundesbank!

The macroeconomic conditions are now sparking food riots. In a new report, titled “Tapering in a Time of Conflict.”, UNCTAD spelt out the scenarios ahead. Sri Lanka, whose debt crisis is several years in the making, is a useful illustration of key dynamics. Remittances and exports collapsed during the pandemic, which also disrupted the crucial tourism sector. The growth slowdown strained the budget and depleted foreign-exchange reserves, leaving Colombo now struggling to import oil and food. The shortages are acute. Two men in their seventies died while waiting in line for fuel, Al Jazeera reported. Milk prices have increased, and school exams were cancelled due to shortages in paper and ink. As Sri Lanka struggles to service the $45 billion in long-term debt it owes, of which over $7 billion is due this year, it could join countries that have defaulted during the pandemic, including Argentina and Lebanon, the latter heavily dependent on wheat imports.

Instead of increasing supply, releasing food stocks and trying to end the war in Ukraine, governments and central banks are hiking interest rates which will increase the debt burden for the food-starved poor countries. As I have explained in previous posts and UNCTAD concurs, central bank interest-rate hikes do nothing to control inflation created by supply disruptions, except to provoke a global recession and an ‘emerging market’ debt crisis.

Increasing protests and political upheaval worry the major powers more than people starving. As US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said: “Inflation is reaching the highest levels seen in decades. Sharply higher prices for food and fertilizers put pressure on households worldwide—especially for the poorest. And we know that food crises can unleash social unrest.”

Back in the 1840s as capitalism became the dominant mode of production globally, Marx talked of a “new regime” of industrial-capitalist food production, connected to the repeal of the Corn Laws and the triumph of free trade after 1846. He associated this “new regime” with the conversion of “large tracts of arable land in Britain,” driven by the “reorganization” of food production around developments in livestock breeding and management, and by crop rotation, coupled with related developments in the chemistry of manure-based fertilizers.

Capitalist food production dramatically increased food productivity and turned food production into a global enterprise. In the mid-1850s, these trends were already apparent: close to 25 percent of wheat consumed in Britain was imported, 60 percent of it from Germany, Russia, and the United States. But it also brought regular and recurring production and investment crises that created a new form of food insecurity. No longer could famine and hunger be blamed on nature and the weather – if it ever could. Now it was clearly the result of the inequities of capitalist production and social organisation on a global scale. And it is the poorest who suffer. Karl Marx once wrote that the famine ‘killed poor devils only’.

And with industrial farming came the cruel exploitation and treatment of animals just as much as humans. Marx wrote in an unpublished notebook, as “Disgusting!” Feeding in stables a “system of cell prison” for the animals. “In these prisons animals are born and remain there until they are killed off. The question is whether or not this system connected to the breeding system that grows animals in an abnormal way by aborting bones in order to transform them to mere meat and a bulk of fat—whereas earlier (before 1848) animals remained active by staying under free air as much as possible—will ultimately result in serious deterioration of life force?”

This is a global crisis and requires global action in the same way that the pandemic should have been dealt with and the climate crisis needs. But such global coordination is impossible while the global food industry is controlled and owned by a few multi-national food producers and distributors and the world economy heads towards another slump.

Courtesy Michael Roberts Blog

Michael Roberts

Michael Roberts worked in the City of London as an economist for over 40 years. He has closely observed the machinations of the global capitalism from within the dragon’s den. Since retiring, he has written several books. The Great Recession – a Marxist view (2009); The Long Depression (2016); Marx 200: a review of Marx’s economics (2018): and jointly with Guglielmo Carchedi as editors of World in Crisis (2018). He has published numerous papers in various academic economic journals and articles in leftist publications.