How is the global recovery after the COVID pandemic going? The economic consensus is that the major economies are recovering fast, driven by rising consumer spending and corporate investment. The problem ahead is not a return to sustained economic growth but the risk of higher or more long-lasting inflation in the prices of goods and services that could force central banks and other lenders to raise interest rates. And that might lead to bankruptcies among highly-indebted companies and then a new financial crash.

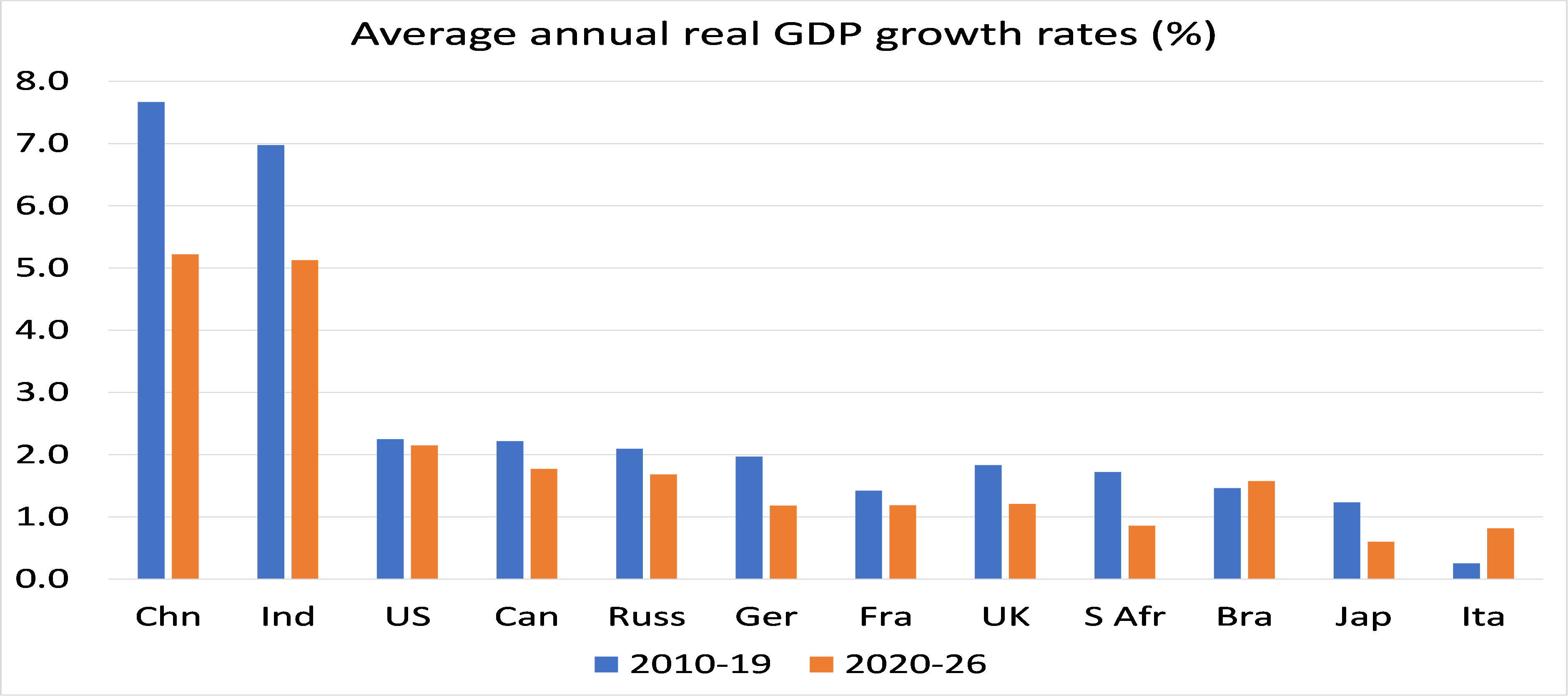

While that risk is clearly there over the next couple of years, will there really be a sustained recovery in economic growth over the next five years? Let’s remind ourselves of the official forecasts. The IMF reckons that by 2024 global GDP will still be 2.8% below where it thought world GDP would have been before the pandemic slump. And the relative loss of income is much higher in the so-called emerging economies – excluding China, the loss is close to 8% of GDP in Asia and 4-6% in the rest of the Global South. Indeed, the forecasts for annual average real GDP growth in virtually all the major economies are for lower growth in this decade compared to the decade of 2010s – which I called the Long Depression.

There seems to be no evidence to justify the claim by some mainstream optimists that the advanced capitalist world is about to experience a roaring 2020s as the US briefly did in 1920s after the Spanish flu epidemic. The big difference between the 1920s and the 2020s is that the 1920-21 slump in the US and Europe cleared out the ‘deadwood’ of inefficient and unprofitable companies so that the strong survivors could benefit from more market share. So, after 1921, the US not only recovered but entered into a (brief) decade of growth and prosperity. During the so-called roaring twenties US real GDP rose 42% and by 2.7% a year per capita. Nothing like that is being forecast now.

And the reason is clear from Marxist economic theory. A long boom is only possible if there has been a significant destruction of capital values, either physically or through devaluation, or both. Joseph Schumpeter, the Austrian economist of the 1920s, taking Marx’s cue, called this ‘creative destruction’. By cleansing the accumulation process of obsolete technology and failing and unprofitable capital, innovation from new firms could prosper. Schumpeter saw this process as breaking up stagnating monopolies and replacing them with smaller innovating firms. In contrast, Marx saw creative destruction as creating a higher rate of profitability after the small and weak were eaten up by the large and strong.

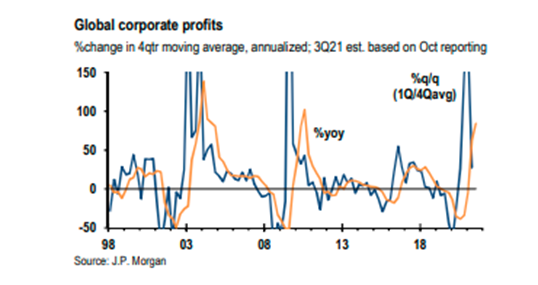

It’s true that, after plunging 35% last year, global corporate profits have staged a huge recovery this year and are on track to end the year at least 5% above their pre-pandemic trend. But if right, this would stand in contrast to global real GDP is expected to remain 1.8%-pt below its pre-pandemic trend.

This rise in profits has spurred some recovery in productive investment (capex), perhaps leading to a 5-10% rise in 2021. But JP Morgan economists think this might be short-lived as their forecasting tool suggests a fall in investment “despite strong profit growth”.

The sharp difference between profits growth and productive investment growth is a key indicator that the 2020s will not be like the 1920s for the US or elsewhere. There are two key reasons: first, continued low profitability (by that is meant profits relative to total investment in the means of production and the labour force); and second, high and rising corporate and other debt. To avoid a slump like 1920-21 or 1929-32, in the Great Recession of 2008-9, governments and central banks slashed interest rates to zero and during the COVID slump added to the easy money policy with huge fiscal stimulus programmes. The result is that there has been no clearing out of corporate ‘deadwood’. Indeed, the so-called zombie companies (where profits are not sufficient to meet borrowing costs) are still here and in growing numbers.

I have mentioned the rise of the zombies on many occasions before in this blog. But there is new evidence to back up the cause of these zombie companies. Two Argentinian Marxist economists, Juan Martin Grana and Nicolas Aguina, recently presented an excellent paper on zombie firms, entitled, A Marxist and Minskyan perspective on zombie firms. See this YouTube recording from 22.36 to 42.30. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4GWUkbGaD-U. Grana and Aquina show empirically that 1) these zombie firms have increased in number since the 1980s and 2) the cause is not the rising cost or the size of their debt but simply because these firms have much lower rates of profit from production, forcing them to borrow more. So zombies have a Marxist, not a Minskyean cause.

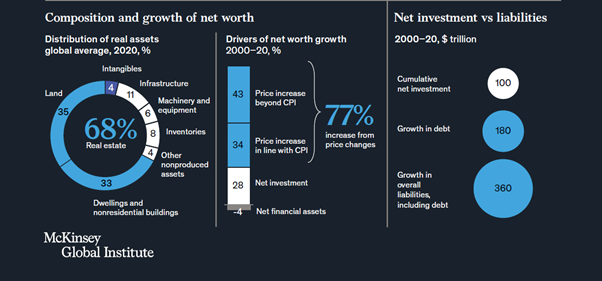

Indeed, because of low profitability on productive capital in most major economies in the first two decades of the 21st century, profits from productive capital have increasingly been diverted into investment in real estate and financial assets, where ‘capital gains’ (profits from rises in stock and property prices) have delivered much higher profits. Over the past two decades, the increase in asset values has primarily come from price increases, rather than through accumulated saving and investment. McKinsey (see below) estimate that somewhat less than 30% of net worth growth in absolute terms was driven by new investment, while roughly three-quarters was driven by price increases. This is making money out of money and not out of the exploitation of labour power. So these gains are either at the expense of those selling at a loss; and/or potentially ‘fictitious’ as eventually the gains will not be realised if the productive sector should plunge.

According to a new report by the McKinsey Global Institute, two-thirds of global net worth (ie the market value of assets less debt) is stored in real estate and only about 20 percent in other fixed assets. Asset values (real estate and financial) are now nearly 50 percent higher than the long-run average relative to annual global income. And for every $1 in net new investment, the global economy created almost $2 in new debt. Financial assets and liabilities held outside the financial sector grew much faster than GDP, and at an average of 3.7 times cumulative net investment between 2000 and 2020. While the cost of debt declined sharply relative to GDP, thanks to lower interest rates, high loans to value produced does “raise questions about financial exposure and how the financial sector allocates capital to investment”.

Higher asset prices accounted for about three-quarters of the growth in net worth between 2000 and 2020, while new investment made up only 28 percent. The value of corporate assets and equity has diverged from GDP and from corporate profits over the past decade. Since 2011, total corporate real assets grew as a weighted average by 61 percentage points relative to GDP across the ten countries. But the corporate profits underpinning those values declined by one percentage point relative to GDP at the global level.

McKinsey is worried that this rising level of speculation in non-productive assets financed by more debt could turn nasty. “We estimate that net worth relative to GDP could decline by as much as one-third if the relationship between wealth and income returned to its average during the three decades prior to 2000. Assessing scenarios including this reversion of net worth to GDP, a reversion of land prices and rental yields to 2000 levels, and a scenario in which construction prices moved in line with GDP since 2000, we find that net worth to GDP by country would decline by between 15 and 50 percent across the ten focus countries.” In other words, a financial and property meltdown.

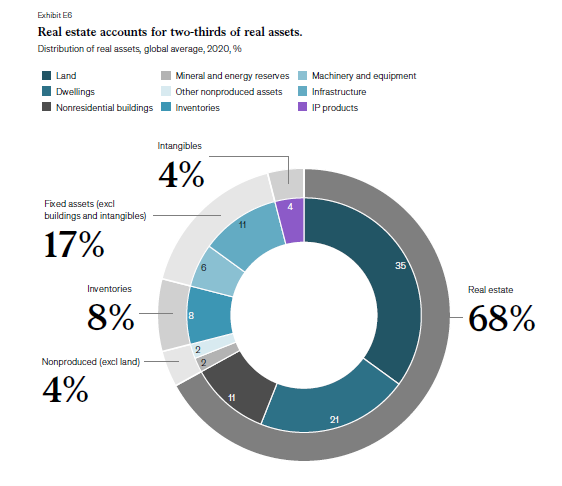

Now some mainstream economists have argued the gap between profitability and investment is misleading because corporations have increasingly been investing in what are called ‘intangibles’. Intangibles are variously defined as investment in intellectual property rights for software, advertising and branding, marketing research, organizational capital and training. These investments do not cost nearly as much as investing in factories, offices, plant, machinery etc (tangible assets) and yet they deliver much more profit and productivity. Or so the argument goes.

Over the past 25 years, McKinsey found that the share of intangibles in total corporate investment growth was 29% compared to just 13% in tangibles. The OECD reported in 2015 that intangible assets had expected returns of 24 percent, the highest rate among produced asset categories.

But here’s the rub. Despite the fact that digital trade and information flows have grown exponentially in the last 20 years, intangibles are still a mere 4 per cent of net worth. They are not decisive in delivering higher investment among corporations in the major economies. Fixed assets and inventories are six times larger.

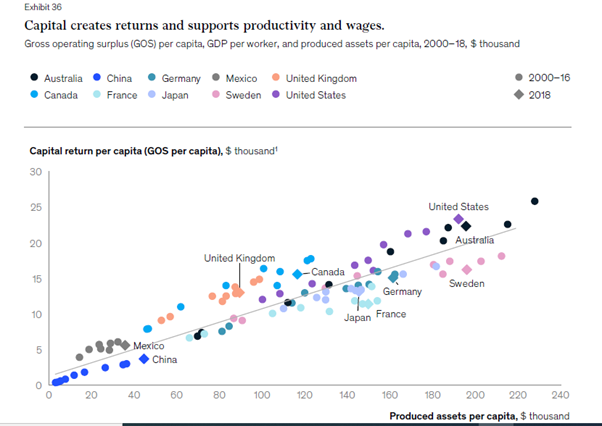

It is still the case that what matters is investment in tangible productive assets. As McKinsey puts it: “Our analysis confirms that gross operating surpluses, which are the value generated by a company’s operating activities after wages are subtracted, increase together with a rising pool of produced assets, which are assets resulting from production, including machinery and equipment and infrastructure as well as inventories and valuables”. The higher the value of produced assets, the more each worker in an economy contributes to GDP, ie a higher productivity of labour.

But the profitability of tangible productive assets has been falling. So, as McKinsey puts it: “If a company invests, say, $1 million in new machinery, will the value of operating that machinery to produce a widget outweigh the value of the land underneath the factory where the machinery sits? If an individual invests in rental property, will any improvements to the property to increase rent be worthwhile compared to simply waiting for market-price appreciation?” For that reason alone, a roaring 2020s is not likely.

Courtesy Michael Roberts Blog

Michael Roberts

Michael Roberts worked in the City of London as an economist for over 40 years. He has closely observed the machinations of the global capitalism from within the dragon’s den. Since retiring, he has written several books. The Great Recession – a Marxist view (2009); The Long Depression (2016); Marx 200: a review of Marx’s economics (2018): and jointly with Guglielmo Carchedi as editors of World in Crisis (2018). He has published numerous papers in various academic economic journals and articles in leftist publications.