Carbon pricing and carbon taxes are now proposed by international institutions and mainstream economics as the main solutions to ending global warming and destructive climate change. For some time, the IMF has been pushing for carbon pricing as ‘a necessary if not sufficient’ part of a climate policy package that also includes investment in ‘green technology’ and redistribution of income to help the worst-off cope with the financial burden. The IMF is now proposing a global minimum carbon price — along the lines of the global minimum floor on corporate taxes which has recently secured agreement.

At the recent meeting of the G20 finance ministers, carbon pricing was endorsed as one of “a wide set of tools” to tackle climate change. Speaking at the Venice International Conference on Climate, Christine Lagarde, president of the European Central Bank, also underscored the need for carbon pricing, emphasising the importance of an “effective carbon price that reflects the true cost of carbon”. An agreed carbon price would then be a precursor to the establishment of a carbon border tax, which would serve as a tariff on imports from countries without carbon pricing. This would be an incentive for others to join the ‘coalition of the willing’.

The EU Commission announced what it calls ‘Fit for 55’ plan to achieve a carbon-neutral EU by 2050 and reduce carbon emissions by 55% below 1990s levels before the decade is out. Again, it looks to carbon pricing to achieve this, as well as carbon import taxes. The EU commission proposes gradually increasing minimum taxes on the most polluting fuels such as petrol, diesel and kerosene used as jet-fuel over a period of ten years. Zero-emissions fuels, green hydrogen and sustainable aviation fuels will face no levies for a decade under the proposed system. Paolo Gentiloni, Brussels economics commissioner, has called the reform a “now or never moment”.

It was no accident that the EU and G20 have turned to William Nordhaus, an American economist and Nobel laureate for economics advice on climate change. Nordhaus gave the keynote address at the Venice conference. He said that “It is a painful, painful realisation, but I think we need to face it: Our international climate policy, the approach we are taking, is at a dead end.” But what was Nordhaus’ answer to this dismal conclusion? He called for a “climate club” of countries willing to commit to a carbon price. “A key ingredient in reducing emissions is high carbon prices,” he said, adding that a “climate club” would have to impose a penalty tariff on countries that did not have carbon pricing in place. Nordhaus said such an approach would help solve the problem of ‘free riding’, which has plagued existing global climate agreements, all of which are voluntary.

Nordhaus has been a major advocate of a ‘market solution’ to climate change. Nordhaus has constructed so-called integrated assessment models (IAMs) to estimate the social cost of carbon (SCC) and evaluate alternative abatement policies. Nordhaus’ IAMs assume that the world economy will have a much larger GDP in 50 years so that even if carbon emissions rise as predicted, governments can defer the cost of mitigation to the future. In contrast, if you apply stringent carbon abatement measures eg ending all coal production, you might lower growth rates and incomes and so make it more difficult to mitigate in the future. Instead, according to Nordhaus, with carbon pricing and taxes we can control and reduce emissions without reducing fossil fuel production and consumption at source.

It is the tobacco/cigarette pricing and taxing solution. The higher the tax or price, the lower the consumption, without touching the tobacco industry. Leaving aside the question of whether smoking has really been eradicated globally by pricing adjustments, can global warming really be solved by market pricing? Market solutions to climate change are based on trying to correct “market failure” by incorporating the nefarious effects of carbon emissions via a tax or quota system. The argument goes that, as mainstream economic theory does not incorporate the social costs of carbon into prices, the price mechanism must be “corrected” through a tax or a new market. But as a recent essay pointed out, the problem is that climate change is not one market failure (like tobacco) but several: in capitalist transport, energy, technology, finance and employment.

Economists who have attempted to calculate what the ‘social price’ of carbon should be have found that there are so many factors involved and the pricing must be projected over a such a long time horizon that it is really impossible to place a monetary value on the ‘social damage’– estimates for the carbon price range from $14 per ton of CO2 to $386! “It is impossible to approximate the uncertainties in low-probability but high-damage, catastrophic or irreversible outcomes.” Indeed, where carbon pricing has been applied, it has been a miserable failure in reducing emissions, or in the case of Australia, dropped by the government under the pressure of energy and mining companies.

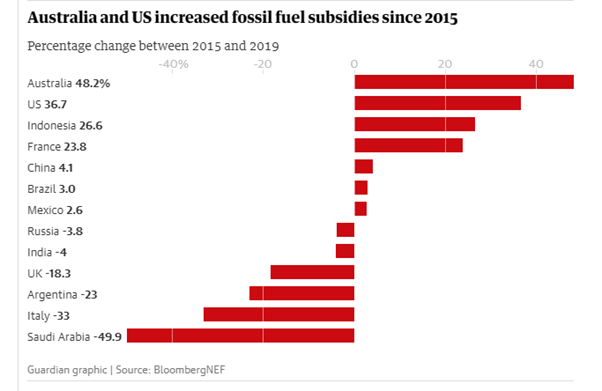

And while there is much talk about raising carbon emission prices, little or nothing is said about the huge subsidies that governments continue to make to fossil fuel industries. EU Commissioner Gentiloni admitted as such: “Paradoxically, [the current energy taxation directive] is incentivising fossil fuels and not environmentally friendly fuels. We have to change this.”

The G20 countries have provided more than $3.3tn (£2.4tn) in subsidies for fossil fuels since the Paris climate agreement was sealed in 2015, a report shows, despite many committing to tackle the crisis. The report says all 19 G20 member states continue to provide substantial financial support for fossil-fuel production and consumption – the EU bloc is the 20th member. Overall, subsidies fell by 2% a year from 2015 to reach $636bn in 2019, the latest data available.

But Australia increased its fossil fuel subsidies by 48% over the period, Canada’s support rose by 40% and that from the US by 37%. The UK’s subsidies fell by 18% over that time but still stood at $17bn in 2019, according to the report. The biggest subsidies came from China, Saudi Arabia, Russia and India, which together accounted for about half of all the subsidies.

The report found that 60% of the fossil fuel subsidies went to the companies producing fossil fuels and 40% to cutting prices for energy consumers. A recent report by the International Institute for Sustainable Development concluded that reforming fossil fuel subsidies aimed at consumers in 32 countries could reduce CO2 emissions by 5.5bn tonnes by 2030, equivalent to the annual emissions of about 1,000 coal-fired power plants. It said these changes would also save governments nearly $3tn by 2030. The International Energy Agency’s road map for net-zero emissions by 2050 calls for a 6 per cent decline in coal-fired generation annually. Yet coal will grow by almost 5 per cent this year, and another 3 per cent in 2022, hitting a new peak.

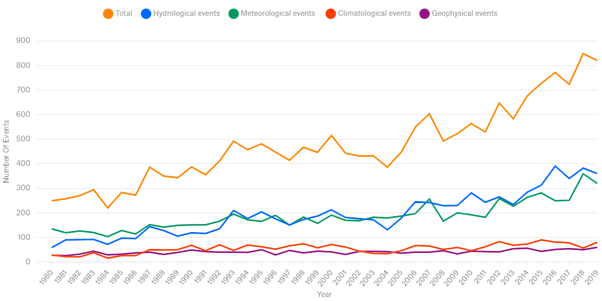

Nordhaus is right. Current climate change policies are at a dead end and the impact of climate change and environmental destruction is getting worse by the day. Earthquakes, storms, floods and droughts — the number of recorded loss events resulting from natural disasters – has been increasing for some years now.

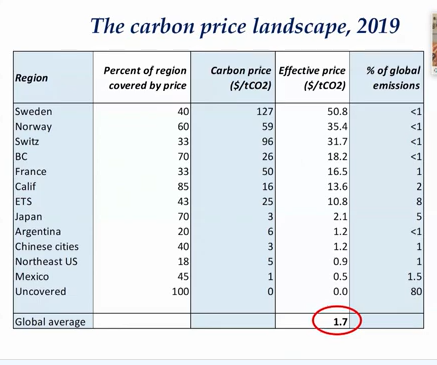

The report also examined how G20 countries were putting a price on carbon pollution. It found that more than 80% of emissions were covered by such prices in France, Germany and South Africa. In the UK, 31% of emissions are covered but the UK has one of highest carbon prices at $58 per tonne of CO2. Just 8% of US emissions are covered and at the low price of $6 per tonne. Russia, Brazil, and India do not have any carbon prices. In his address to the G20, Nordhaus showed that the current average global carbon price is under $2 and 80% of global emissions have no carbon emissions pricing market at all!

So the carbon pricing and taxation solution, even if it worked to lower emissions, is a pipedream as it can never be implemented globally before global warming reaches dangerous ‘tipping points’. All the latest climate science suggests that the tipping points are approaching fast and allowing fossil fuel production to continue while trying to reduce its use by ‘market’ solutions’ like carbon pricing and taxes will not be enough. Even the IMF has admitted that market solutions have not worked.

Market solutions are not working because for capitalist companies it is just not profitable to invest in climate change mitigation: “Private investment in productive capital and infrastructure faces high upfront costs and significant uncertainties that cannot always be priced. Investments for the transition to a low-carbon economy are additionally exposed to important political risks, illiquidity and uncertain returns, depending on policy approaches to mitigation as well as unpredictable technological advances.” (IMF)

Indeed: “The large gap between the private and social returns on low-carbon investments is likely to persist into the future, as future paths for carbon taxation and carbon pricing are highly uncertain, not least for political economy reasons. This means that there is not only a missing market for current climate mitigation as carbon emissions are currently not priced, but also missing markets for future mitigation, which is relevant for the returns to private investment in future climate mitigation technology, infrastructure and capital.” In other words, it ain’t profitable to do anything significant.

What is the alternative? Mark Carney, former Bank of England governor and climate change envoy for the UN and many multi-nationals, reckons it is ‘regulation’. “We need clear, credible and predictable regulation from government,” he said. “Air quality rules, building codes, that type of strong regulation is needed. You can have strong regulation for the future, then the financial market will start investing today, for that future. Because that’s what markets do, they always look forward.”

Carney’s answer is really an excuse for continuing to expand fossil fuel production. Although the IEA recently said that the world was to stay within 1.5C Paris target increase in global heating, there could be no more exploration or development of fossil fuel resources, Carney argues that countries and companies could still carry on exploiting fossil fuels, if they use technology such as carbon capture and storage, or other ways of reducing emissions. “With the right regulation, with a rising carbon price, with a financial sector that is oriented this way, with public accountability of government, of financial institutions, of companies, yes, then we can, we certainly have the conditions in which to achieve [holding global heating to 1.5C“.

This is disingenous nonsense. Carbon pricing schemes just hide the reality that, as long as the fossil fuel industry and the other big multinational emitters of greenhouse gases are untouched and not brought into a plan for phasing them out, the tipping point for irreversible global warming will be passed. Instead of waiting for the market to speak, and for ‘regulation’, we need a global plan where fossil fuel industries, financial institutions and major emitting sectors are brought under public ownership and control.

Who are the biggest emitters or consumers of carbon apart from the fossil fuel industry? It is the richest wealth and income earners in the Global North who have excessive consumption and fly everywhere. It is the military (the biggest sector of carbon consumption). The waste of capitalist production and consumption in autos, aircraft and airlines, shipping, chemicals, bottled water, processed foods, unnecessary pharmaceuticals and so on is directly linked to carbon emissions. Harmful industrial processes like industrial agriculture, industrial fishing, logging, mining and so on are also major global heaters, while the banking industry operates to underwrite and promote all this carbon emission.

A global plan could steer investments into things society does need, like renewable energy, organic farming, public transportation, public water systems, ecological remediation, public health, quality schools and other currently unmet needs. And it could equalize development the world over by shifting resources out of useless and harmful production in the North and into developing the South, building basic infrastructure, sanitation systems, public schools, health care. At the same a global plan could aim to provide equivalent jobs for workers displaced by the retrenchment or closure of unnecessary or harmful industries. Planning not pricing.

Courtesy Michael Roberts Blog

Michael Roberts

Michael Roberts worked in the City of London as an economist for over 40 years. He has closely observed the machinations of the global capitalism from within the dragon’s den. Since retiring, he has written several books. The Great Recession – a Marxist view (2009); The Long Depression (2016); Marx 200: a review of Marx’s economics (2018): and jointly with Guglielmo Carchedi as editors of World in Crisis (2018). He has published numerous papers in various academic economic journals and articles in leftist publications.