‘Hedging’ used to be a way reducing the risk of selling or buying. Farmers waiting for their harvest to come in are uncertain about what price per bushel they will get at the market: will they get a price that makes them a profit and a living for next year or will they be made destitute? To reduce that risk, hedge companies offer to buy the harvest in advance at a fixed price. The farmer is guaranteed a price and income whatever the price per bushel at the time of going to market. The hedge fund takes the risk that it can make a profit by buying the harvest at a price below the eventual market price. In this way, ‘hedging’ can smooth out the volatility in prices, often very high in agricultural and mineral sectors.

But in financial markets, hedging and hedge funds take on a whole new function. It has become a game, with billions of other people’s money at stake, turning the market for goods and services into a casino for financial betting. In my previous post, I explained how what Marx and Engels called ‘fictitious capital’ (stocks and bonds) and their supposed value bore little relation to the real value of underlying earnings and assets of companies.

Financial hedging takes this one step even further away from real values, as hedge funds do not just buy or sell stocks rather than invest in productive capital. Now they bet on which way the price of any stock will go. In ‘short selling’, a hedge fund borrows shares in a company from other investors (for a fee) and sells the shares on the market at, for example, $10 each. Then it waits until they fall to $5 and then buys them back. The borrowed shares are returned to the original owner and the hedge fund pockets a profit.

Far from smoothing price changes, by betting on prices falling or rising, the hedge funds actually thrive on increased volatility. ‘Going long’ to drive up the price and ‘going short’ to drive down the price is the name of the game. And in doing so, ‘short sellers’ can actually drive companies into bankruptcy, with the loss of jobs and incomes for thousands.

In the year of COVID, while the ‘real economy’ collapsed, those with cash to spare and looking for a return (banks, pension funds, rich individuals) invested heavily in the stock market, often using borrowed money (at near zero rates of interest). And these big investors put much of their money into hedge funds and look to these so-called ‘smart people’ to make them a buck. And they have been doing so, big time.

But also in the year of the COVID, there were millions of people who have been working at home or have been furloughed sitting on savings that they cannot spend because of lockdowns and no travel. So many have linked up through social networks like Reddit to bet on the stock market.

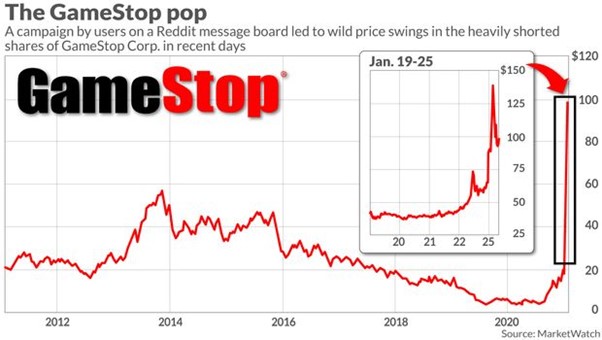

These small investors have recently started to combine and build up some firepower and to take on the big institutions in their gambling dens. Since the beginning of the year, a group of amateur traders, organised on Reddit, have been playing the market against major hedge funds, who had shorted shares for GameStop: a US-based video game retailer. This company had suffered badly during the year of the COVID and was expected to go bust. Hedge funds piled in to ‘short’ the stock.

But the small traders did the opposite and used their firepower to drive up the stock price, forcing the hedge funds, backed by the big banks and institutions, to buy back the shares at higher prices as the time ran out for their ‘short’ bets (they are fixed time contracts). As a result, several ‘shorting’ hedge funds took a huge loss ($13bn) and one fund had to be bailed out by its investors to the tune of $2.75 billion.

Wall Street is furious. The small investors have ‘rigged’ the market, they cry, threatening the value of your pension funds and putting banks in jeopardy. This is nonsense, of course. What it actually shows is that financial markets are ‘rigged’ by the big boys and it’s small investors who are usually the ones that get ‘shafted’ and swindled in this gambling den. As Marx said, the financial system “develops the motive of capitalist production”, namely “enrichment by exploitation of others’ labour, into the purest and most colossal system of gambling and swindling and restricts even more the already small number of exploiters of social wealth” (Marx 1981: 572).

Of course, in the current battle, the small investor will lose out in the end. Massachusetts state regulator William Galvin has already called on the New York Stock Exchange to suspend GameStop for 30 days to allow a cooling-off period. “This isn’t investing, this is gambling,” he said. No sweat! And already, small investors are seeing a hike in the charges and limits on their trades by brokers and market makers (the casino owners) to deter them from trading. And there is talk at the top of ‘regulating’ the market to stop investors ‘ganging up’ on the ‘legitimate’ institutions of Wall Street. The price of GameStop is now falling back.

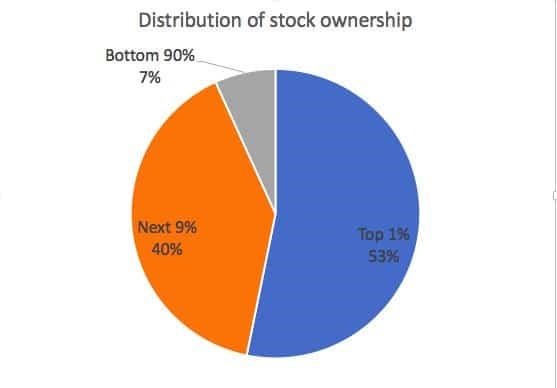

For working people all these shenanigans may appear irrelevant. After all, most working households have little or no shares at all. The top 1% of households owned 53% of US stock market wealth, with the top 10% owning 93%. The bottom 90% own only 7%. However, workers’ pensions and retirement accounts (if workers have them) are invested by private pension fund managers into financial assets (after deducting very nice commissions). So what savings working households do have are vulnerable to the gambling activities of the swindlers in the financial casino – as the global financial crash of 2007-8 showed.

What this little story of GameStop shows is that company and personal pension funds run by the ‘smart people’ are really a rip-off for working people. What is needed are state funded pensions not subject to the volatility of the financial game. The big hedge funds have been burnt in this latest skirmish by some small investors and they want to get these minions out of the game. What working people should want is to stop this game altogether.

Courtesy Michael Roberts blog

Michael Roberts

Michael Roberts worked in the City of London as an economist for over 40 years. He has closely observed the machinations of the global capitalism from within the dragon’s den. Since retiring, he has written several books. The Great Recession – a Marxist view (2009); The Long Depression (2016); Marx 200: a review of Marx’s economics (2018): and jointly with Guglielmo Carchedi as editors of World in Crisis (2018). He has published numerous papers in various academic economic journals and articles in leftist publications.